Discovering God

How the Greek intelligentsia sought the path towards Orthodoxy in the twentieth century

How the Greek intelligentsia sought the path towards Orthodoxy in the twentieth century

Athanasios Zoitakis, candidate of historical sciences

The nineteenth century heralded the departure from Orthodoxy for a significant many Geeks. Enchanted by the brilliance of the culture of “civilized Europe”, Greek intellectuals opened their country to foreign influences. From the West there came materialism, theosophy, Marxism, rationalism, scepticism and nihilism. There appeared in Greek cities a fashion for all things foreign, and the word ‘cultural’ became a synonym’ for ‘technological’ and ‘Western’.

In the latter half of the nineteenth century Greek cities had lived through a profound spiritual crisis. On the one hand, there were the poor and on the other the well-to-do and wealthy who possessed a great many servants and could lead the way of life of aristocrats. Overseas customs and attire had become the fashion, as had conspicuous spending and a life of idleness. The upper layers of society treated the conservatism of the Orthodox faith with open contempt and mocked popular piety.

The hierarchy of the Greek Orthodox Church, which was under the control of the state, remained to all intents and purposes silent. The monasteries barely recovered after an anti-monastic campaign waged by the authorities. Parish priests were immersed in many material issues and could not find time to engage with their flock.

It was within these conditions that laymen and women came to the rescue of Orthodoxy. Many intellectuals discovered the path to God and brought their compatriots with them. Today we shall speak about three outstanding representatives of Greek art: a writer, an architect and a painter. In an environment of de-Christianization they demonstrated that modern-day secular culture can be built upon tradition and can still preserve its Orthodox features.

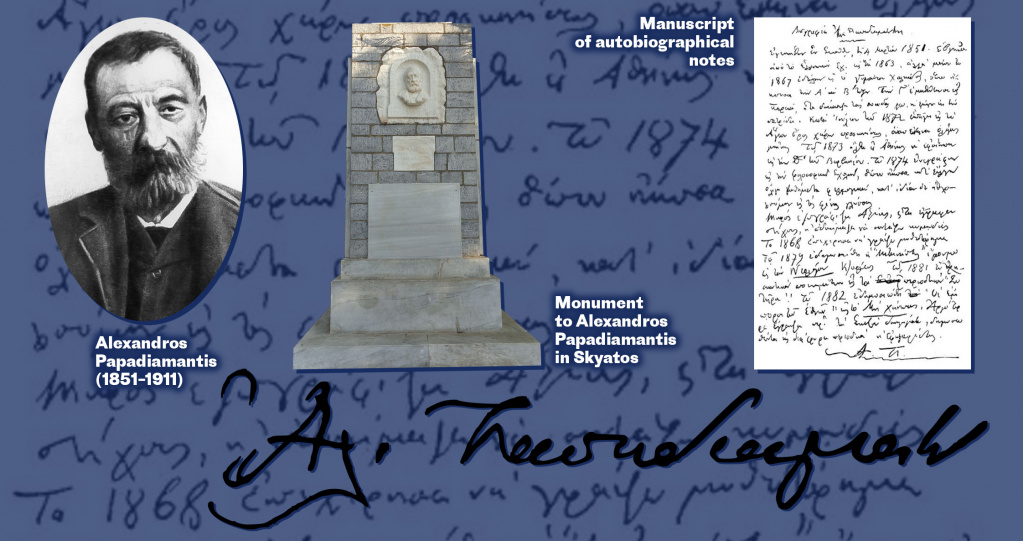

Alexandros Papadiamantis (1851 – 1911)

A major prose writer of his time. His works enjoy deserved recognition in his homeland and have been translated into many European languages, including Russian.

Papadiamantis was born on the island of Skiathos to the family of a priest. He joined the faculty of philology at the University of Athens, but financial difficulties obliged him to interrupt his studies and earn money to maintain himself. This is how his first short stories, articles and translations appeared.

Papadiamantis was a man of a kind and modest disposition. Finding himself in the alien atmosphere of the capital, the writer experienced an acute moral and psychological crisis. He found a resolution to it in the Orthodox faith. The writer led an ascetic way of life as a ‘monk in the world’ by withdrawing into prayer and reflection.

Papadiamantis wrote verses and liturgical texts but was renowned most of all for his short stories. He possessed the unique gift of seeing within each individual instance the global meaning of what was taking place.

The two hundred and more stories written by Papadiamantis form an encyclopedia of the mores and customs of those living on the island of Skiathos with its numerous churches and monasteries, they are a unique chronicle of the life of the peasants and fishermen from Greece’s other regions and the poor quarters of Athens. In them we find all of Greece with her beauty, joy and afflictions.

Like Dostoevsky (Papadiamantis’ favourite author), he displayed active love to each one of his heroes. Alexandros Papadiamantis appealed to all to be merciful towards the outcast and humiliated, and this appeal ran through most of his stories.

Papadiamantis would conduct himself, as he would like to write, as a “poor, sodden, shaking dove”, and this was regarded by the godless world as demonstratively odd.

Papadiamantis takes compassion upon sinners and does not pass moral judgment upon people. This does not mean that the writer was an idealist – he clearly saw the problems of the society he lived in and reflected them in his works: “Here we see clearly how mammon is turned into a god. It would be a thousand times better if people had stuck to the idol worship of the ancients. Today the dominant religion is dirty and bestial materialism. Christianity is used only as a cover for it.”

Papadiamantis’ work is unique in the context not only of Greek, but also of world literature. His works capture not only the mores typical of the Greek provinces, its way of life and character, but also reflect the history of the country, popular traditions and the Orthodox faith. It is within all of this, Papadiamantis believes, that there is concealed the inexhaustible fount of the spiritual strength of the Greek nation.

Papadiamantis was the first of his generation who turned to Orthodoxy and the traditional popular culture for a source of inspiration. His example and experience have exerted a noticeable influence upon modern Greek society.

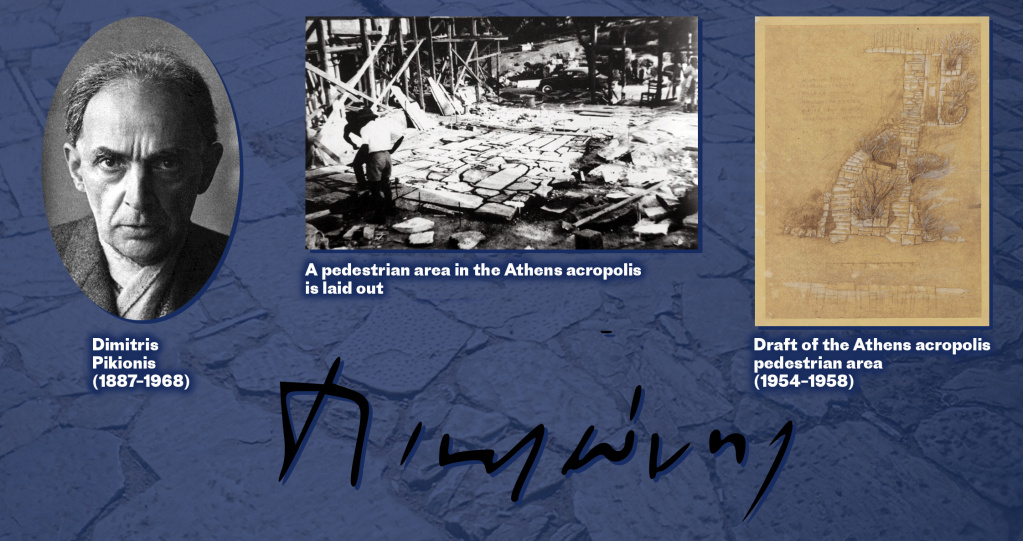

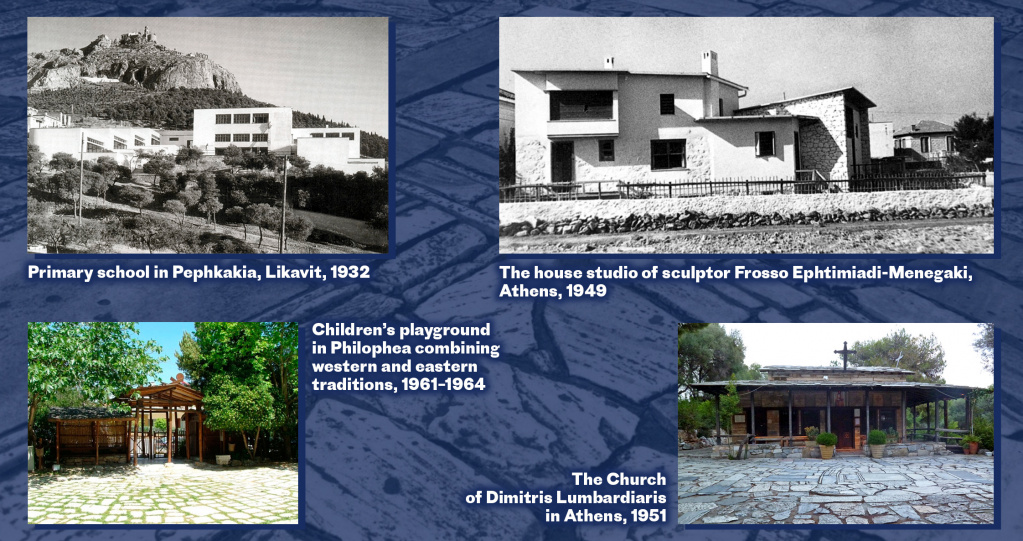

Architect and artist Dimitris Pikionis

Born in 1887 in Piraeus, he studied civil construction in Greece and then continued his studies in Paris and Munich.

Returning to Greece, he became a professor at the Techinical University and set about realizing his architectural projects. He built new primary schools, summer theatres, houses and children’s playgrounds.

Anyone who has visited Athens at least once will have come across Pikionis’ work. One of his main works is the superbly executed pedestrian zones within the archeological area of the Athens acropolis.

Unlike most of his contemporaries, Pikionis believed that architect was a craft and not an art. He himself was not only an architect, but also a philosopher and a thinker who opened up for Greek art new aesthetic horizons.

Pikionis’ art was unique and innovative. He was inspired by Byzantine and ancient Greek art and the architectural schools of the peoples of the world. And yet at the same time he avoided imitation, finding his own individual style.

The Orthodox faith became for Pikionis the most important source of inspiration. In spite of the fact that his family and work took away much of his time, he devoted all of his free time to the service of God. The great architect would spend the nighttime studying the Philokalia, the writings of the Holy Fathers and in prayer.

The Orthodox faith became for Pikionis the most important source of inspiration. In spite of the fact that his family and work took away much of his time, he devoted all of his free time to the service of God. The great architect would spend the nighttime studying the Philokalia, the writings of the Holy Fathers and in prayer.

“Pikionis was the new St. John Climacus, a humble recluse and thinker who embodied his spiritual insights in architectural forms,” one contemporary writer wrote of him.

Ethnographer and publisher Photis Kondoglou

Photis Kondoglou (1897 – 1965) was a unique figure, who brought others in various layers of Greek society to respect the Orthodox tradition, was a writer, iconographer, ethnographer and publisher.

He heralded from Asia Minor and lived and studied in Europe for five years where he became renowned for his unique talent as a painter and published his first literary works. In 1922 Kondoglou returned to Greece and was based in Athens. Photis was struck by peoples’ the total infatuation with the West and the absence of spiritual searching among the capital’s intelligentsia. He went against the desperate searches of his colleagues by expounding a Christian world outlook. The protection, preservation and spreading of Orthodox and popular culture became the meaning of his life. Kondoglou is not merely an artist and writer, but also a polemicist, advocate and missionary.

In his painting Kondoglou – one of the most outstanding iconographers in modern times – was an adherent of the Byzantine tradition. He not only reintroduced it to Orthodox church buildings, but also used the technique to produce works which would appear to be remote from this genre such as portraits, landscapes and still lifes. To Kondoglou’s brush there belong frescoes, mosaics and icons in many of Greece’s Orthodox churches. He worked as a restorer in the Athens Museum of Byzantine Art, the monasteries of Mount Athos and the Coptic Museum in Cairo.

The artist’s work was not imitative, but was a reimagining of the Byzantine legacy. A little earlier than Kondoglou other artists aiming to reproduce Byzantine models had begun to work in this style, which made their works look like museum exhibits. Unlike them, Kondoglou imbued Orthodox art with vitality and made it contemporary.

Kondoglou is no less well known as a writer. He used popular language, enriching it with elements of local dialects. The writer’s works are distinguished by a lofty artistry and profound knowledge of life. Kondoglou was an ardent proponent of studying popular customs and spirituality and actively encouraged the development of ethnographic research. Photis, moreover, reintroduced his fellow countrymen to the literature of the Lives of the saints and revived the Byzantine art of adornment through manuscript miniatures.

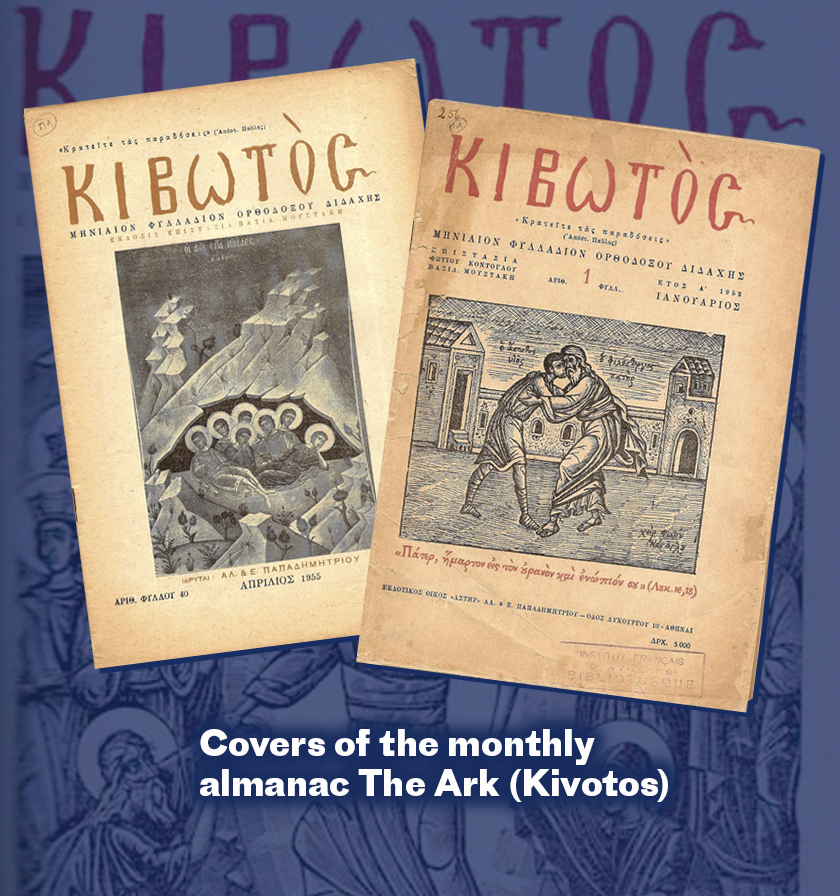

Kondoglou played a significant role as a populiser of the Byzantine legacy. From 1950 onwards he published in the newspapers his stories on Orthodox traditions and feast days. In addition, he published the monthly almanac The Ark, calling upon his readers to fight for Orthodox values. Photis Kondoglou’s varied activities served as a catalyst for the return of Greek society to the Orthodox tradition in all its aspects. It is thanks to Kondoglou that traditional Orthodox iconography returned home to the churches and that Byzantine chant edged out Western part song.

Kondoglou raised a great number of disciples who continued his cause: the museum specialist Symon Karas, who aroused in his contemporaries interest in the Byzantine musical ecclesiastical and secular tradition; Angelika Khadzimikhali, who began the first serious study of Greek popular applied art; Anastasios Orlandos and Aristotelis Zakhos, who worked upon the revival of Byzantine architecture; the iconographers and painters S. Papaloukas, S. Vasilliou, R. Kopsidis, P. Vambulis, Ya. Terzis, D. Ksinopulos and N. Eggonopulos, who continued the cause of rehabilitating Byzantine art and its reintroduction to Orthodox church buildings.

Certain aspects of the history of the Christian Church remain insufficiently studied to this day. In particular, we know far less of the spiritual lives of the simple laity than we do of the priests and monastics. The current epoch has allowed us to widen considerably the possibilities of gathering and retaining information. It has become evident that laymen and laywomen have often played an important role in the preservation of Orthodox culture and its transmission to subsequent generations.

Our article has examined some of these episodes. It is important to emphasize that the participation of the intelligentsia in the defence of Orthodoxy was not a uniquely Greek phenomenon. It is sufficient to recall the religious awakening in the Russian empire at the turn of the twentieth century. A small monastery – the Optina hermitage – attracted the best intellectual forces of Russian society. Similar episodes are to be found in the history of all Orthodox nations. At a time of crisis, it was the representatives of culture who found within themselves the strength to look at the surrounding reality not from the point of view of gain, but from the perspective of eternity and eternal values. It is quite possible that in our time we shall see a similar religious awakening. Perhaps it is being born before our very eyes…