The Fair Sun of the Land of Russia

Arkady Tarasov, candidate of historical sciences, docent of the Department of Pre-Modern Russian History at the History Faculty of Moscow State University

The baptism of Rus, so I believe, is one such phenomenon that has the same consequences as a nuclear explosion for Russian history, or at least for the history of her culture. The other two instances of such are the reforms of Peter the Great and the Bolshevik Revolution. The ‘shock waves’ that each of these events released led history in a new direction.

The baptism of Rus should not, of course, be understood as an event that took place in a single moment in the year 988 anno domini. All the more so can we allow that the recent pagans in the blink of an eye became Christians and that the land of the eastern Slavs immediately became in some miraculous manner the ‘Holy Russia’ that did not then exist, the ideal of which some of contemporaries often sigh for. Scholars have long since confidently understood the baptism of Rus to be the culmination of events, the sum of which became the spread of Orthodoxy at first as a state religion supported by the political elite and then only as the faith of the majority of the population of Rus.

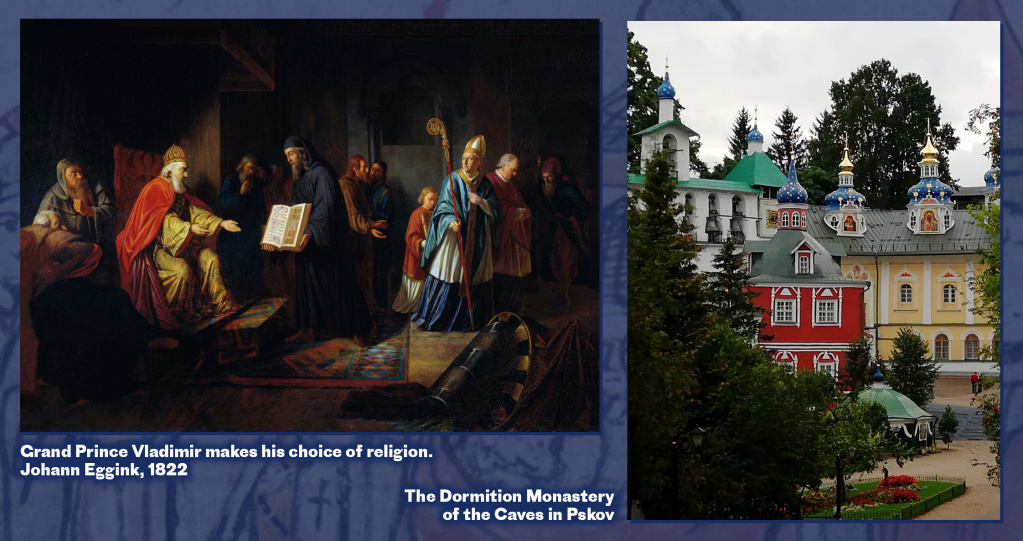

At the same time, there can be no doubt that fundamental for the Christianization of Rus were the deeds of prince Vladimir Svyatoslavovich, canonized amongst the saints as ‘equal-to-the-apostles’ and in legends receiving the name of the ‘Fair Sun’. The acceptance by Vladimir and his retinue of Eastern Christianity at the end of the 980s became the lodestar for the Christianization of the state of Old Russia and led to the creation of a new ecclesiastical organization – the metropolitanate of All Rus under the jurisdiction of the Patriarch of Constantinople.

The significance of Kiev for the religious history of the eastern Slavs is not only great but huge. Kiev, the capital of the Riurikovich dynasty, was to become the main city of Russian Orthodoxy, the Old Russian Jerusalem and Constantinople. It was most likely here, and not in Chersoneses, that prince Vladimir received baptism. It was here that Christianization began, accompanied by the overthrowing of the idols of the pagan gods and the mass baptism of the population. It was here that the see of the Russian metropolitanate was set up, the primates of which for centuries, even after the transfer of the see, continued to bear the title ‘of Kiev’. It was upon the hills of Kiev that there arose the Monastery of the Caves – the foundation of the Old Russian monastic tradition, the most important centre of Slavic book learning, the ‘smithy of servants’ of the Russian Orthodox Church.

The idea of Kiev as a special sacred space became widespread already at a time close to that of when prince Vladimir was active. In his Sermon on Law and Grace, written in the middle of the eleventh century, the first ethnic Russian to become a metropolitan – Hilarion – describes Kiev as being ‘holy’ and ‘most glorious’ under the protection of the Mother of God. It is no later than the beginning of the twelfth century that there appears in the Tale of Bygone Years (the so-called ‘Primary Chronicle’) the telling legend entitled the ‘Sermon on the baptism of Rus and of how the Holy Apostle Andrew came to the land of Rus’. According to this sermon, the apostle Andrew, journeying fr om Chersoneses to Rome, came to rest on the hills above the river Dniepr where he spoke these prophetic words to his disciples: “‘You see these hills? It is upon these hills that the grace of God shall shine forth, that there will be a great city and God will there raise up many churches’. And upon ascending theses hills, he placed a cross there, and prayed to God, and descended from these hills wh ere later the city of Kiev would appear.” The author of the Tale of Bygone Years placed in the mouth of prince Oleg words that would later become a common-place phrase when the prince ascended the throne of Kiev: “May this become the Mother of Russian cities.”

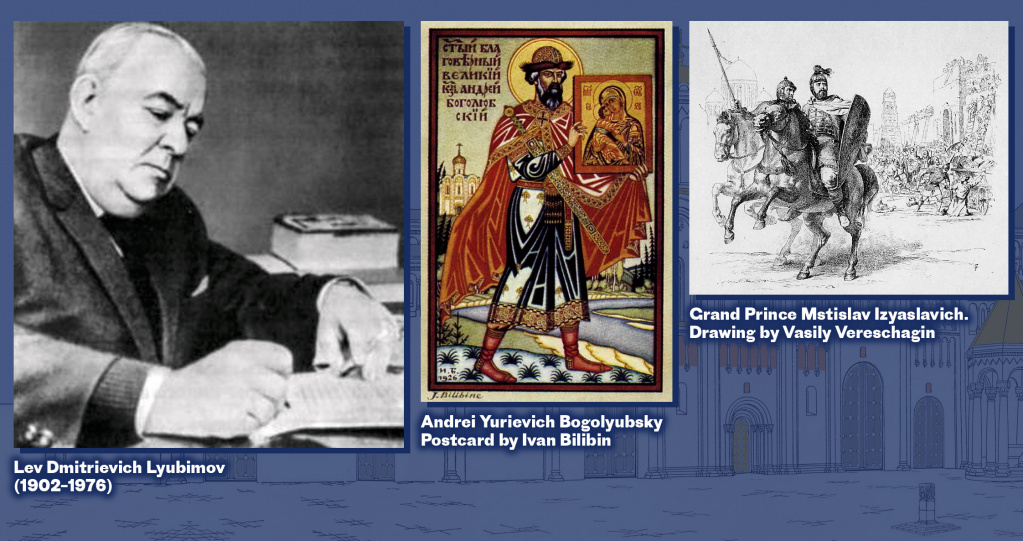

Kiev became for Rus the lawgiver and trendsetter in the field of high art, which in the Middle Ages was exclusively religious. In turn, the Kievan tradition was sustained by the juices of Byzantine culture which had reached its zenith by that time. The art historian Lev Lyubimov called the growth of Rus after the reception of Christianity the “great continuity”. The academician Dmitry Likhachev considered the word “influence” altogether inadequate in reflecting the real significance of Byzantium in Russian history: “In many instances it would therefore be more correct to speak not so much of the ‘influence’ of individual cultural phenomena of Byzantium, but of the direct transplantation of these influences.” The best Byzantine architects laboured on the churches of Kiev, gifted artists created for them brilliant mosaics, bright frescoes and magnificent icons, and refined orators worked upon books that were to become like “rivers filling the cosmos” and created the libraries of Kiev.

Secular and church people in other cities and other parts of the land of Rus used the Kievan models in their work. When the state of Old Russia disintegrated politically, the most vainglorious and powerful princes would try to replicate in their capitals the image of a ‘new Kiev’. Andrei Bogolyubsky did so in Vladimir-on-the Klyazma, as did Mstislav Izyaslavich in Vladimir of Volhynia. And so did many others. The time of disintegration came to an end to be replaced by a new state of eastern Slavs with their capital in Moscow, but the ‘idea of Kiev’ did not perish in the river Lethe; rather, it received a new lease of life. By the turn of the fifteenth century, as the contemporary scholar Andrei Ranchin has observed, the Kievan period was perceived by the learned bookmen of Moscow “as the ‘golden age’ of Rus interrupted by the invasion of the Mongol khan Batu and now undergoing a renaissance in the actions of the state of Muscovy.” The official ideology of Muscovy gained even greater currency during the reign of Ivan III (1462 – 1505), who actively developed the doctrine of the unity of the Russian lands and who located their sources above all in the era of Kievan Rus.

Ivan III was the grand prince of Moscow who drew not only from the tradition of Muscovy. In his missive to the envoys of Novgorod in November of 1470 for the first time he invokes the names of Riurik, St. Vladimir and Vsevolod the ‘Big Nest’ by characterizing them as consistent bearers of the idea of the unity of Rus. Ivan III’s reference to Riurik and Vladimir, that is, his harkening back to the world of Kievan Rus, reminded people of the time when no single tribe enjoyed dominance of the Russian lands. The official Church also viewed things in the same light, believing, among other things, that the Kievan period and the period of the ascendancy of Muscovy comprised a single metropolitanate not torn apart by contradictions.

We may remark that the search for analogies in antiquity was not merely limited to the political sphere. Church politics in the 1460-70s was also galvanized. The Voskresenie chronicle, which reflected the official perspective of the state (the Moscow grand princely compilation of 1479 was used as its basis) mentions in 1471 the “holy and great prince” Vladimir who had baptized “all our lands.”

Subsequently, Vladimir Svyatoslavovich – baptized as Basil – would be revered by grand prince Vasily III Ivanovich (1505 – 1533), the son and heir of Ivan III. In 1514, before he began his campaign against Smolensk and on the eve of the 550th anniversary of the demise of Vladimir in 1015, he laid the foundation stone of the Church of St. Vladimir ‘in the Gardens’ in Moscow, which would become only the second church building dedicated to St. Vladimir in north east Rus.

The scheme of Kiev – Vladimir – Moscow, which has survived and flourished for centuries, has become the cornerstone for modern-day ideas for the history our more than thousand-year-old homeland.