Ecumenical Patriarch. The History of One Title

Pavel Kuzenkov, Candidate of History, specialist in Church History and Historical Chronology, Associate Professor of the Faculty of History of Moscow State University and of the Sretensky Theological Seminary, a lecturer at the Moscow Theological Academy.

The full title of the Primate of the first – according to the diptych – Local Orthodox Church is well known. It is”Archbishop of Constantinople – the New Rome and Ecumenical Patriarch.” It seems to be generally understood that the term “Ecumenical” here is just a lofty Byzantine title, nothing more than a tribute of respect to the ancient tradition. Indeed, according to the Orthodox teaching, no one, except Jesus Christ, is empowered with the “world-wide jurisdiction.” Just as the apostles were carrying out their God-given mission in brotherly unanimity, but independently, so also the Orthodox Churches founded by them are sisters united in the Holy Spirit as individual parts of the One, Holy, Catholic and Apostolic Church. However, people unaware of the subtleties of canon law and unacquainted with church history perceive this formula differently. In their vision, based exclusively on the core meaning of the term “universe,” this title implies the official recognition of the role of the first among the Patriarchs as the leader of world Orthodoxy. Meanwhile his entire flock throughout the world numbers some six million [1], which is about 2% of the entire number of Orthodox Christians [2].

What does the title “Ecumenical” mean then? Where does it come from and what is its true purport?

Empire as Universe

First of all it is necessary to gain insight of the word “universe or inhabited world” (οἰκουμένη in Greek). It is a passive participle of the verb οἰκέω with several meanings (live, inhabit, populate) that is used without the implicit noun “earth,” or, word-for-word, - “a terrestrial space rendered habitable by man.” That was how the ancient Greeks referred to the land where they lived and which they knew, as different from far-off regions, either uninhabited or inhabited by wild barbarians. Usually, “universe” did not refer to the whole world as such, but only to those of its parts where there was civilization. The rulers of big kingdoms were called the “kings of the earth,” as for example, King Cyrus of Persia is called in the Bible (Ezra 1:2). So, when the Greaco-Roman civilization was united under the Roman emperors, the Roman Empire began to be called the “world.” It is precisely in this sense that St. Luke used this word speaking about the Nativity of Christ in his Gospel:”In those days a decree went out from Emperor Augustus that all the world should be registered” (Lk.2:1). In fact the term “oikoumene” implied not so much a populated space as a cultivated space of ancient civilization. Other cultures had their own “worlds,” and such understanding of the term had lasted for many centuries. For example, sending a copy of the Kormchaia Kniga (the Pilot Book) to Metropolitan Cyril II of All Russia in 1262, Bulgarian ruler Jacob Svetoslav wrote: “Let the Russian world be enlightened by your word.”

When in 325, St. Constantine the Great, Equal-to-the-Apostles, summoned bishops from all over his Empire to Nicaea to discuss general ecclesiastical problems, that gathering got the name of an “Ecumenical Council.” Thus, an institute of all-imperial level came into being, which at the call of the emperors on especially important occasions brought together bishops from all over the vast Roman state to consider such problems under the chairmanship of the most authoritative bishops, who with the time began to be called “heads of the fathers” – Patriarchs.

Most frequently the epithet “of the whole world” in the sense of “empire-wide,” “state-wide” was used by Justinian the Great (527-565) in legal texts. The words “world,” “world-wide” referred to the territory of the Empire as a whole are often to be found in his legislative acts. Thus, the Emperor’s novella 109 of 541 offers a detailed explanation of the supreme church institutes – the Ecumenical Councils and Patriarchates in the following way: “Just as the fathers did, we call ‘heretics’ those who are adhering to different heresies… as in fact are all who are not members of the Holy, Catholic and Apostolic Church of God, in which all the most holy Patriarchs of the whole World – of Western Rome, of this royal city, of Alexandria, of Antioch and of Jerusalem – t

ogether with all the most reverend bishops subordinate to them, unanimously proclaim the apostolic faith and holy tradition.” [3]

So, according to the imperial legislation, the Orthodox faith was proclaimed together by five “Patriarchs of All the World” in unity with the bishops subordinate to them; and it was precisely to witness this unanimity that the emperors used to call together Ecumenical Councils. The order of honoring the Patriarchs is defined by canons (Second Ecumenical, 3; Fourth Ecumenical, 28; Trullo, 36) and fixed in the legislative acts of the Roman Empire (Codex Iustiniani, I.1.7, I.2.16; Novella Iustiniani 131, and others). According to the rank of their see, the order is this: Rome, Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, and Jerusalem. It is important to mention that this list of the five patriarchal sees by no means exhausted the number of the autocephalous Local Churches, as beyond this list there remained not only churches which at that time were located outside the Empire (the Church of Georgia, the Church of Aquileia), but also a few independent churches within the Empire’s borders – the Churches of Cyprus, of Carthage, and of Justiniana Prima. The pentarchy, according to Emperor Justinian, was symbolizing the unity of the Orthodox Church, with the primates of the Empire’s five most authoritative sees as its guarantors.

And, most importantly, all the five Patriarchs were considered “ecumenical.”

From five “Patriarchs of All the Universe” to one “Ecumenical Patriarch”

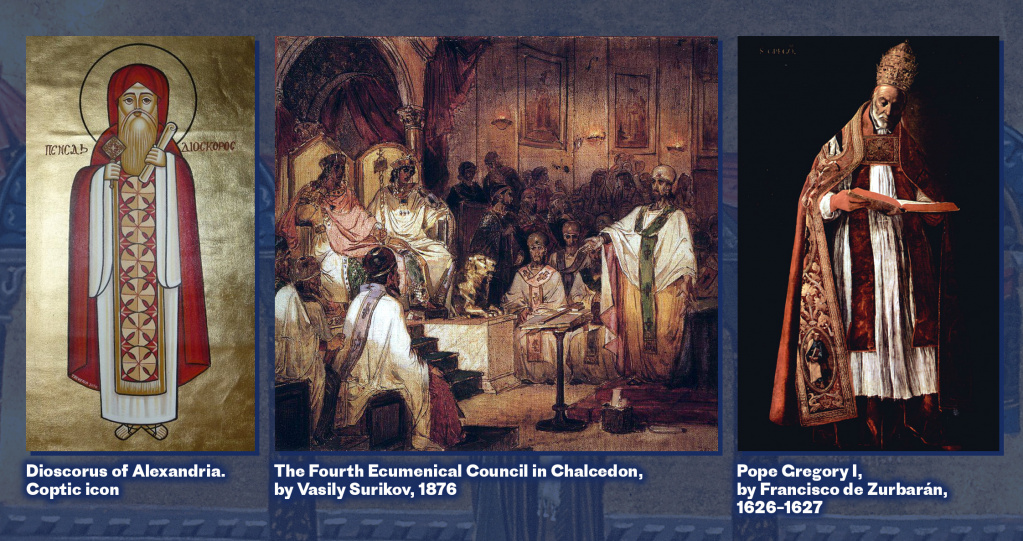

In the sources that have come down to us, the epithet “ecumenical” in reference to bishop’s title is first found in the acts of the so-called Robber Council of Ephesus (449). In his speech, Bishop Olimpio of Euaza titled the steersman of that scandalous pseudo-council, Dioscorus of Alexandria, “our most holy father and ecumenical archbishop of the great city of Alexandria” [4] At the Council of Chalcedon two years later, the legates of Pope Leo the Great signed the documents on behalf of “our lord, His Beatitude Apostolic Father of the Ecumenical Church, Bishop of the city of Rome” [5].

However, it is only in the legislative acts of Justinian, beginning from 530, the formula “Ecumenical Patriarch” started to be officially used in the title of the archbishops of Constantinople – the New Rome [6] outside Byzantium, This novelty was not noticed immediately outside Byzantium, but when it was, it evoked sharp rebuff from the See of Rome. St. Pope Gregory I found Constantinople’s claim to the dominance in the Church in the word “ecumenical,” about which he expressed his bitterness writing to Eulogius of Alexandria [7]. Writing in return Eulogius, as well as the then Patriarch of Constantinople himself assured the Pope that the term was no more than just a high-sounding ceremonial title and that of course he, the Pope, as the Primate of the Apostolic See, was the true leader of the Christians all over the world…

The conception of all patriarchal sees being ecumenical prevailed in Byzantium for many centuries. Thus, at the Seventh Ecumenical Council, John, representative of the Patriarch of Jerusalem referring to the holy patriarchs called them the “pastors of the universe.” St. Theophanes the Confessor wrote in his famous ‘Chronography’ that he was going to mention in this work the years of life and service of the hierarchs of the great ecumenical sees, namely, of Rome, Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch and Jerusalem; those who had been safeguarding the Church in a due Orthodox manner, and those who, plunged in heresy, had been ruling like robbers. [9]

It was not unusual that in the 9th century, papal envoy Anastasius the Librarian to his direct question he asked in Constantinople about the meaning of the title “ecumenical” got the answer that the Patriarch was called Ecumenical (oecumenicus, universalis) not because he was the bishop with control over the whole world, but because he had an administrative power over one of the parts of the world inhabited by Christians. [10]

Later, Byzantine canonists Theodore Balsamon (9th century) and Matthew Blastares (14th century) asserted that “the regions of four climates” of the world were divided among the five Patriarchs, with the exception of the territories of the “minor Churches – those of Bulgaria, Cyprus, and Georgia, which were not subordinate to any one of these Patriarchs. In order that the rights of the churches not to be violated, none of the Patriarchs “was permitted to introduce stauropegia in a country subject to another Patriarch, nor to take away clerics from it.” [11]

For all that notwithstanding, the idea of some specific unique prerogatives of Constantinople found its way into the imperial legislation and into Byzantine nomocanons. For example, the Nomocanon in 14 Titles in the edition of 880 speaks (Title I, ch. 5) about the ranks of the patriarchs… and about Constantinople being at the head of all churches, referring the reader to the texts of the First Book of the Code (Title I, ch. 7; Title 2, ch. 6, 20, 24) and to those of Novellas (Title 1, ch. 2; Title 2, ch. 3). The First Book of the Code in its Title 2, ch.16 says that “Constantinople has the presidency over all.” [12] Then, the Isagoga of Emperor Basil I (886) echoing this text, asserts that “the See of Constantinople, as royally distinguished one, was declared first by council decisions and that following these decisions, the sacred laws prescribe for litigations that may happen in other churches, to be submitted for its (Constantinople’s) consideration and judgment.”[13] But what is remarkable, none of the Nomocanon texts acknowledges Constantinople as the “head of all churches;” neither does any one of the laws prescribe the world-wide jurisdiction for the See of Constantinople. But if referred exclusively to the territory of the Empire, the statements of the Nomocanon and Isagoga are fair.

The point is that by the 9th century Byzantium had lost all its lands in the East and in the West, and its borders narrowed to coincide with those of the territory under the canonical jurisdiction of the Patriarchate of Constantinople. And since the force of application of the legislative codes was limited within the borders of the Empire, the use of the prerogatives of Constantinople specified in them was also limited to the same territory. In this situation, the “Ecumenical” is fully in agreement with the original implication of the term which equates “universe” to the Roman (Byzantine) Empire.

From a “millet-bashi” to the “leader of world Orthodoxy”

In 1453, the Byzantine Empire fell. Constantinople became the capital of an Islamic power – the Ottoman Empire. All Orthodox Patriarchates again found themselves united within one state, though on a different legal basis. Since the application of the Sharia law did not extend to Christians and Jews, they were accordingly divided into autonomous ethnoreligious corporations – millets, each with their own spiritual leader at the head. Moved from St. Sophia to the Phanar quarter, the Patriarch of Constantinople became one of such leaders – a millet-bashi. According to the Turkish laws, he was granted jurisdiction over all Orthodox Christians living under the rule of the Sublime Porte. Using their new status, the Phanar patriarchs began to interfere rather actively in the affairs of other Local Churches, but only to be confronted with a firm canonically-based position of their primates in response. Patriarch Meletius Pegas of Alexandria was brief and explicit presenting this position in a letter of 1592 to Jeremiah II of Constantinople: “No patriarchal see is subordinate to another.” [14]

The letter was written in connection with Jeremiah’s attempts to declare himself as the leader of world Orthodoxy in the dialogue with the Protestants, who at that time were actively looking for allies in their vehement struggle against papacy. “The Ecumenical Church is the fatherland for churches; it presides over conducting things…It has got the eldership in Orthodoxy and its place is at the head,” Jeremiah II was convincing Tubingen theologians in 1576. [15]

Taking advantage of the patronage insured by the Muslim authorities and the flouting Orthodox canons, Phanariotes were trying to fill the title of the “Ecumenical Patriarch” with real content by positioning Constantinople as the leader of the entire Orthodox world. In November 1872, Russian ambassador to the Sublime Porte, Count Nikolai P. Ignatiev, commenting on the situation around the Patriarchate of Jerusalem, reported to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs: “The attempts by the Phanariote Greeks to raise the See of Constantinople above all others, to attribute the status of primacy to it, similar to the papal see in the Western world, and to look on the assets of other Churches as their own property are becoming more and more apparent. This group hopes that on becoming the master of the Orthodox world, Phanar would take over riches for the benefit of lay Phanariotes running the Ecumenical Patriarchate.” [16]

It is noteworthy that the patriarchs of Constantinople in their turn used to express strong and unambiguous disapproval of similar attempts of papal Rome to justify its superiority over other Churches. The Patriarchal and Synodal Encyclical of 1895 clearly stated that “each particular self-governing Church, both in the East and West, was totally independent and self-administered in the time of the Seven Ecumenical Councils. And just as the bishops of the self-governing Churches of the East, so also those of Africa, Spain, Gallia, Germany and Britain managed the affairs of their own Churches, each by their own local synods, the Bishop of Rome having no right to interfere, and he himself also was equally subject and obedient to the decrees of synods. But on important questions which needed the sanction of the universal Church an appeal was made to an Ecumenical Council, which alone was and is the supreme tribunal in the universal Church. Such was the ancient constitution of the Church.” [17]

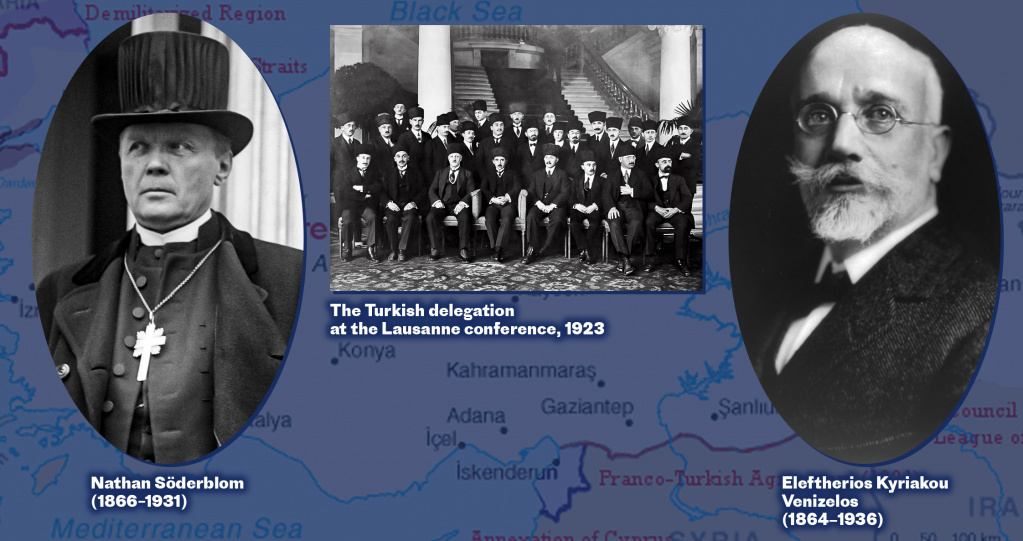

The collapse of the Ottoman Empire created an illusion in the Greek world about the implementation in the near future of the “Great Idea” – the restoration of Byzantium with the help of the victorious Entente. Against this background, an idea was born in the depths of Phanar to turn the Ecumenical Patriarchate into a world interchurch Christian center. On February 11(January 29 OS), 1920, the Synod of Constantinople with the Locum Tenens at the head (the Patriarchal See had been vacant since the autumn 1918) issued an encyclical letter “Unto the Churches of Christ Everywhere,” in which it proposed establishing a kind of a world pan-Christian League of Churches on the pattern of the League of Nations. The word Κοινωνία in Greek means more than just a “union, community;” it also implies “ecclesiastical fellowship, communion,” which fact attaches to it a specific character, important “for the preparation and advancement of that blessed union” of Christians of all confessions “which will be completed in the future in accordance with God’s aid.” [18] The ambitious project met approval of many Orthodox hierarchs and aroused agile interest of the Swedish Lutheran Archbishop Nathan Söderblom, one of the founders of the ecumenical movement. Negotiations started on the preparations for a pan-Christian “Ecumenical Council” to take place in 1925, the jubilee year marking an anniversary of the First Council of Nicaea (325).

But political developments interfered with these dreams. The Greco-Turkish War ended with the expulsion of the Entente troops from Constantinople and deportation of the Greek population from Turkey, revived by Kemal Atatürk. At the Lausanne Conference of 1923, the Kemalists insisted on the expulsion of the “Greek” Patriarchate, which was why the title “Ecumenical” had to be used for completely different purposes. The Greek delegation led by Eleftherios Venizelos stated that the Ecumenical Patriarchate was the “primate” among all Orthodox Churches… and in the questions of faith, Christian morality and church law, the opinion and authority of the Ecumenical Patriarchate were of crucial importance. [19] Under the pressure of the French and English participants, the Turks made concessions: the Patriarch and Phanariotes were permitted to stay in Istanbul on the condition of no intervention in politics whatsoever. And the “Ecumenical Council” had to be forgotten …

The past century has brought no improvement to strengthen the position of the Ecumenical Patriarch in Turkey. On the contrary, the Greek population of Phanar has sharply reduced. On the canonical territory which 1570 years ago the Council of Chalcedon brought under the jurisdiction of Constantinople, the Ecumenical Patriarch is practically left without parishioners. The major part of his flock lives now in America and in Western Europe. Such situation called for an explanation. Consequently, the Constantinople canonists have started, timidly at first, but with gradually increased confidence, to play out in their writings the idea that it is only right and proper for the hierarch adorned with the title “Ecumenical” to have a “world-wide” jurisdiction. To justify this thesis, all kind of episodes from the past and old-time precedents torn out from the context are being collected and the long-clarified church canons misinterpreted. The ancient title is being exploited especially actively.

In 2008, addressing the Assembly of the European Parliament, Patriarch Bartholomew said, among other things: “As a purely spiritual institution, our Ecumenical Patriarchate embraces a truly global apostolate that strives to raise and broaden the consciousness of the human family – to bring understanding that we are all dwelling in the same house. At its most basic sense, this is the meaning of the word ’ecumenical’ – for the ‘oikoumene” is the inhabited world – the earth understood as a house in which all peoples, kindreds, tribes and languages dwell.”

As for the English-speaking audience, the word “ecumenical” – “universal” – of Bartholomew’s patriarchal title has a specific connotation related to the well-known Protestant movement for the unity of all Christians. If in the Russian church lexicon, the terms “universal” and “ecumenical” are antipodes, in English and in Modern Greek they are one word. In the texts coming out from the pen of today’s apologists of the so-called “new ecclesiology,” it is more and more difficult to draw the line between the two connotations. The original term of the time of Justinian the Great, implying a special role of the five ecumenical patriarchs of the Empire as the pillars and guarantors of Orthodoxy, has somehow imperceptibly transformed into the “Ecumenical Patriarch” as the claimant both to the status of the “leader of the Orthodox world” [20] and that of a “supra-confessional” leader of all Christianity at the same time. In the light of the above, the recent initiative of Patriarch Bartholomew about a meeting of church leaders in 2025 to be timed to coincide with a jubilee anniversary of the First Ecumenical Council (325) and to work out a “more determined ecumenical course” [21] does not seem fortuitous.

Notes

1. Wikipedia’s Russian and English editions both mention 5.3 million; the Greek edition – about 6.6 million

2. 300 million according to Russian Wikipedia (with reference to: Juergensmeyer M., Roof W. C. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Global Religion. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications, 2012. Vol. 1. P. 319). According to the Greek edition the number is between 200 and 260 million; the English one speaks about 220 million.

3. Corpus Iuris Civilis. T. III: Novellae. Berlin, 1963 (8 ed.). P. 518.

4. Acta Conciliorum Oecumenicorum. T. II.3.1. Berlin; Leipzig, 1935. P. 187; Деяния Вселенских Соборов. Т. 3. Казань, 1908. С. 168. (Acts of the Ecumenical Councils, V. 3, Kazan, 1908. P.168)

5. Acta Conciliorum Oecumenicorum. T. II.1.2. Berlin; Leipzig, 1933. P. 141; T. II.3.2. 1936. P. 415–416; Деяния Вселенских Соборов. Т. 4. Казань, 1908. С. 56. (Acts of the Ecumenical Councils, V. 4, Kazan, 1908. P.56)

6. См.: Codex Iustiniani, I.2.24; I.1.7.

7. Epistula 9, cap. 12.

8. Acta Conciliorum Oecumenicorum. Series 2. T. III.1. Berlin; New York, 2008. P.188–189; Деяния Вселенских Соборов. Т. 7. Казань, 1909. С. 80. (Acts of the Ecumenical Councils, V. 7, Kazan, 1909. P.80)

9. Theophanis Chronographia / Ed. C. De Boor. Leipzig, 1883. Vol. 1. P. 3.

10. Acta Conciliorum Oecumenicorum. Series 2. T. III.1. Berlin; New York, 2008. P.1–2; Деяния Вселенских Соборов. Т. 7. Казань, 1909. С. 26. (Acts of the Ecumenical Councils, V. 7, Kazan, 1909. P.26)

11. Σύνταγμα τῶν θείων καὶ ἱερῶν κανόνων. Ἀθῆναι, 1992. Τ. 6. Σ. 257–258.

12. Juris Ecclesiastici Graecorum historia et monumenta / Ed. I. B. Pitra. Romae, 1868. T. II. P. 462–463; Нарбеков В. Номоканон Фотия с толкованиями Вальсамона. Казань, 1899. Ч. 2. С. 56–58.(Vasiliy A. Narbekov, Photius’s Nomocanon with Balsamon’s Commentary, Kazan, 1899, Part 2, P. 56-58)

13. Collectio librorum juris Greco-Romani ineditorum / Ed. C. E. Zachariae von Lingenthal. Lipsiae, 1852. P. 66–68.

14. Μεθόδιος (Φούγιας), μητρ. Ἐπιστολαί Μελετίου Πηγᾶ, Πάπα καὶ Πατριάρχου Ἀλεξανδρείας (1590–1601). Αθῆναι, 1976. Σ. 19, 21.

15. Καρμίρης Ι. Τὰ δογματικὰ καὶ συμβολικὰ μνημεῖα τῆς Ὀρθοδόξου Καθολικῆς Ἐκκλησίας. Τ. 1. Ἀθῆναι, 1960. Σ. 476.

16. Каптерев Н. Ф. Сношения Иерусалимских патриархов с русским правительством. СПб., 1898. Ч. 2. С. 804.

(Nikolai F. Kapterev, The Relationship of the Patriarchs of Jerusalem with the Russian Government, St. Petersburg, 1898, Part 2, P.804)

17. https://azbyka.ru/otechnik/bogoslovie/okruzhnoe-patriarshee-i-sinodalnoe-poslanie-konstantinopolskoj...

18. Καρμίρης Ι. Τὰ δογματικὰ καὶ συμβολικὰ μνημεῖα… Τ. Βʹ. Ἀθῆναι, 1953. Σ. 957–960.

19. Lausanne Conference on Near Eastern Affairs (1922–1923). Records of Proceedings and Draft Terms of Peace. London, 1923. P. 324, 335.

20. The “leader of the Orthodox world” is precisely how US Secretary of State Michael Pompeo called Bartholomew in his Twitter in November 2020 — URL: https://www.ekathimerini.com/news/259272/pompeo-hails-patriarch-as-key-partner/

21. Church Times, 19 February 2021. URL: https://www.churchtimes.co.uk/articles/2021/19-february/news/world/after-1700-years-let-s-talk-again...