The Myths and Legends of Metropolitan Stephan

Archpriest Igor Prekup, priest of the Estonian Orthodox Church under the Moscow Patriarchate.

The metropolitan of Estonia Stephan spoke on the Greek TV channel 4E of the path the Church of Estonia has followed in confessing Christ in her homeland:

“The history of martyrdom here in Estonia covers eight centuries. Yet not all of these centuries were similar to each other. Before the twelfth century Estonia was invaded by the Danes, then for a period of two hundred years there were the German Crusaders and then after them for another two hundred years we had the Swedes and then for another two centuries the Russians. Our history in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries is to a significant degree a history of martyrdom as our Church had to be strong. Out of a population of one and a half million there are two hundred thousand Orthodox believers. And in 1945, when the communist system took over Estonia and closed our Church, liquidated it and in an uncanonical manner installed a metropolitan from Russia, it was then that persecution began. The first persecutions began in 1920 when the hieromartyr bishop Plato was martyred, the first Estonian bishop, along with two other priests…”.

It is hard to disagree with metropolitan Stephan that the history of martyrdom in the land of Estonia goes back over eight centuries. But we should clarify the fact that this was not a universal Christian martyrdom but precisely Orthodox martyrdom.

The people of Estonia have, of course, suffered greatly, having repeatedly found themselves on the verge of extinction as a result of plague or becoming a battleground first in the Livonian War, then in the Northern Wars. Yet, if we are to speak of martyrdom, then a martyrdom and confessing of Christ common to all Christians begins here in the short period of the Red Terror at the end of 1918 and the beginning of 1919, and then unfolded in 1940 when there occurred what among simple people is known as the ‘Soviet occupation’, and what various politicians, in striving for terminological precision, call the ‘incorporation’ or ‘annexation’. But regardless of what one calls this phenomenon which lead to the spread of the Bolshevik campaign against God throughout Estonia, the fact remains that it was precisely at this time that a widescale common Christian martyrdom began here and that there were individual instances of martyrdom.

But before this we may speak of only of an Orthodox confessing of Christ and martyrdom. And this is why this historical phenomenon is eight centuries old, that is, from the time when the Crusaders decided to take it upon themselves to bring Christian enlightenment to our land in the twelfth century by violently interrupting the spreading of the Orthodox tradition. Until their arrival the preaching of Christianity here was done in a peaceful manner, from both the West and the East. And it was Russian missionaries who left an indelible trace in the Estonian language. For example, words that are fundamental to preaching such as ‘rist’ (‘cross’, in Russian krest) and ‘raamat’ (‘book’, from the Slavonic word gramota, meaning ‘document’). The Estonian verb ‘ristima’ (from the Russian krestit’, meaning ‘to baptize’) points towards the rootedness in the consciousness of medieval Estonians of being enlightened from the East because it is in the Russian language that the mystery of being born into eternal life is denoted by a word establishing a link between the Cross of Christ and the cross which every Christian bears through life. For comparison’s sake, we should note that in many European languages this sacrament is signified by words originating from the ancient Greek ‘baptismo’, which literally means ‘I immerse’, in German ‘taufen’, meaning ‘to plunge into water’.

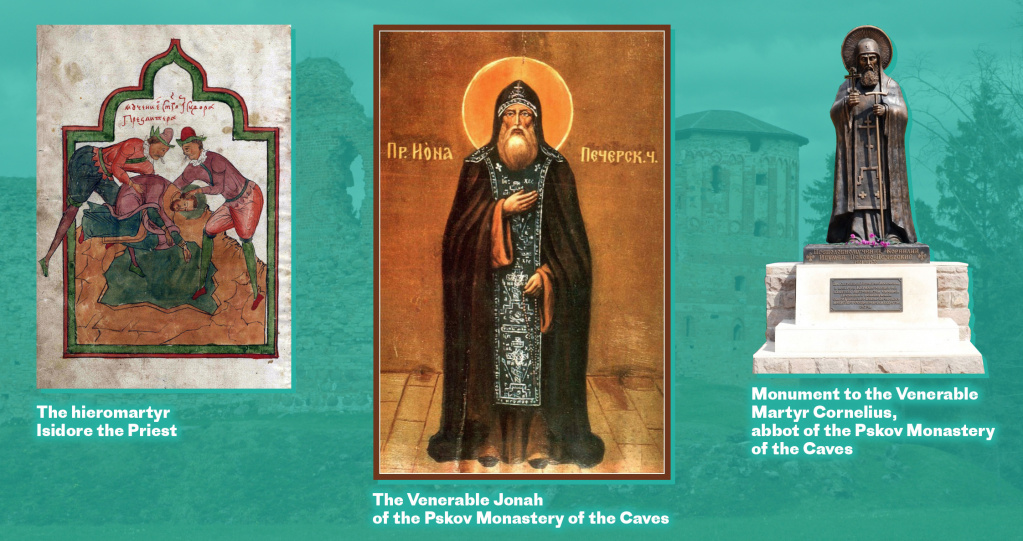

In Tartu (founded in 1030 by prince Yaroslav the Wise as the city of Yuriev) Orthodoxy survived up until 1472 when the parish priest St. Isidore of Yuriev was martyred along with seventy-two parishioners. The priest Ioann Shestnik (later taking the name Jonah when he became a monk) escaped from here to Pskov, where he founded the Pskov Monastery of the Caves. The venerable abbot Cornelius preached Orthodoxy not only to the Estonians who lived within the vicinity of the monastery but also went as far as Narva and founded parishes in Neuhausen (now Vastseliina) and other places.

The Orthodox confessing of Christ was renewed here in 1841 when a spontaneous movement arose (going against, incidentally, ‘local traditions’ and the state imperial policy in the Ostsee region) by which Latvian and Estonian peasants converted to Orthodoxy. The persecutions enacted against them by the Ostsee German nobility were especially harsh.

Metropolitan Stephan, however, did not want to point out that the local Orthodox confessing of Christ and martyrdom came about as a result of persecution by non-Orthodox Christians. Of course, we can easily understand this politically correct smoothing out of sharp corners, but we can hardly approve of it.

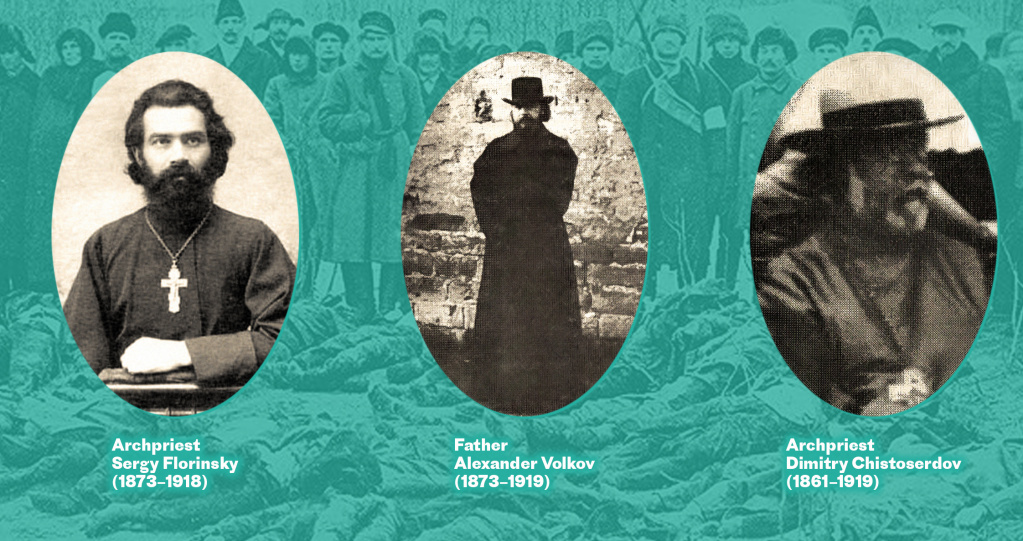

In recalling the persecutions of the last century, metropolitan Stephan rightly draws our attention to the first Orthodox ethnic Estonian bishop the hieromartyr Plato (Kulbusсh). However, I believe it important to note that, firstly, the persecution of the faithful took place not in the 1920s (if metropolitan Stephan is referring to the expulsion by the Estonian authorities in the summer of 1920 of number of Orthodox priests to Soviet Russia, then I would be happy to agree with him…); secondly, metropolitan Plato was chronologically not the first to be martyred among the Estonians. He was killed on 14th January 1919, a year after his episcopal consecration, which took place on 31st December 1917 (31st January 1918 on the new calendar). The red commissars Kull, Otter and Riatsepp, apart from metropolitan Plato, shot archpriests Nikolai Bezhanitsky and Mikhail Bleive. However, somewhat earlier there suffered at the hands of the Bolsheviks the hieromartyrs Sergy Florinsky (30th December 1918) and then Alexander Volkov and Dimitry Chistoserdov (8th January 1919).

I cannot rid myself of the suspicion that what metropolitan Stephan means by ‘Estonian new martyrs’ is ‘new martyrs of Estonian nationality’. Perhaps the symbolism of the accepting of martyrs’ crowns by a Russian (Father Nikolai) together with Estonians (bishop Plato and Father Mikhail) doesn’t quite fit into his historical picture? And perhaps it is awkward for him to deal with this fact as in the historical period under discussion Estonian Orthodoxy was in canonical unity under the omophorion of the holy confessor Patriarch Tikhon of Moscow and All Russia?

And I also believe it appropriate to emphasize that all the new martyrs of the Estonian Church – both Estonians such as bishop Plato (Kulbusch), Fathers Mikhail Bleive and Ioann Pettai and Russians such as Fathers Nikolai Bezhanitsky, Sergy Florinsky, Alexander Volkov and Dimitry Chistoserdov – were all one in confessing fidelity not only to God and his Church but also, in particular, to the mother Russian Orthodox Church. The blood of the new martyrs of Estonia is the seed of unity of Estonian Orthodoxy. All attempts to destroy this unity are nothing other than the desecration of their memory.

Metropolitan Stephan states that “in 1945, when the communist system took over Estonia and closed our Church, liquidated it and in an uncanonical manner installed a metropolitan from Russia, it was then that persecution began”. There is much confusion in these words. Let us begin with the fact that the communist system took over Estonia in 1940. The last day of the independent Estonian state of the inter-war period is officially considered to be 6th June 1940. Repressions that affected in the first instance White emigrés and members of organizations considered to be politically hostile (even the Russian Student Christian Movement fell into this category) began quickly (arrests and imprisonment in camps or executions by firing squad), and in 1941 more than nine thousand people were sent into exile. For small Estonia this was a huge number of people, but soon in 1944 another seventy or eighty thousand people emigrated to the West, and then after the war in March 1949, as apart of Operation Priboi 20 723 people were deported in the opposite direction.

Almost a year after the installation of Soviet power on the territory of Estonia on 30th March 1941 there was the canonical reunification of the Estonian Apostolic Orthodox Church (EAOC), which then consisted of the dioceses of Tallinn and Narva, with the mother Church of Russia. The reunification of the EAOC with the Russian Orthodox Church took place after the preliminary agreement to this step with the parishes and the repeated appeals of the head of the EAOC metropolitan Alexander (Paulus) to the locum tenens of the Patriarchal Throne metropolitan Sergius (Stragorodsky) with the request to “forgive with love the involuntary sin of separation”. And what is quite important is that this reunification happened by repenting of the sin of the schism of 1923 when metropolitan Alexander, in the hope of receiving autocephaly, transferred the Estonian Orthodox Church to the jurisdiction of the Patriarchate of Constantinople without even attempting to receive the blessing of the holy martyr Patriarch Tikhon of Moscow to do so, having sworn an oath three years earlier to remain loyal to the hierarch of the Russian Church.

At the beginning of the Nazi occupation metropolitan Alexander appealed to the Nazi authorities to tear away once more the EAOC from the Moscow Patriarchate; however, he managed to do this only with diocese of Tallinn, while the diocese of Narva, headed by archbishop Paul (Dmitrovsky) remained in canonical unity with the confessor Church.

For some reason it is awkward for metropolitan Stephan to recall these details from the historical and canonical life of Estonian Orthodoxy as he prefers to concentrate attention on the year of 1945. So why 1945 if the Soviet regime returned here in September of 1944? Probably because in 1945 there took place the canonical reunification with the Mother Church of the diocese of Tallinn that had separated during the German occupation. Directly after this the process, begun in 1941, was completed of transforming the EAOC, which consisted of two dioceses, into a single Estonian diocese with its see in Tallinn. Let me emphasize that it was not the liquidation of the autonomous EAOC on the territory of Estonia that happened, as metropolitan Stephan asserts, but its transformation.

The transformation into a regular diocese for its survival in “certain circumstances”. Yes, autonomous status was lost for many long years; yes, there was a change of name; yes, the structure changed (one diocese instead of two), but all of this was done so that the Local Church, the kernel of which is the diocese, could continue her work and mission. Therefore, the assertion that the communist system “closed our Church, liquidated it and in an uncanonical manner installed a metropolitan from Russia, and it was then that persecution began” is a lie from beginning to end as there was no closure or liquidation, while persecution, as we have already noted, began directly after the installation of the Soviet regime in 1940 and merely continued after the war.

I consider it of separate importance to examine the assertion that the communist system “in an uncanonical manner installed a metropolitan from Russia”. We will let metropolitan Stephan’s conscience deal with the identification of the Holy Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church with the “communist system”. We will only clarify that the Holy Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church installed not a metropolitan but an archbishop, and not from Russia but from Estonia, and not just anybody but a good pastor – archbishop Paul (Dmitrovsky), who up until then had headed the diocese of Narva that had been liquidated in the transformation process.

But why, then, does metropolitan Stephan in his interview not explain what is meant by the “uncanonical nature” of installing archbishop Paul to the diocese of Tallinn? He would not happen to have in mind the metropolitan installed from Turkey, who, according to the 16th Canon of the local Council of Constantinople of 861, had been wrongly installed while the ruling bishop was still alive, that is, metropolitan Alexander who fled abroad in 1944 with about twenty-two other priests (the exact number is not known)? More interestingly, has not metropolitan Stephan shown his own hand here? It was precisely he, metropolitan Stephan (Charalambidis), who was installed in 1999 by Patriarch Bartholomew to the see of metropolitan of Tallinn and All Estonia, which was occupied at the time by the hereditary citizen of Estonia metropolitan Cornelius (Jakobs), who was still alive at the time and living not somewhere in emigration but in Tallinn.

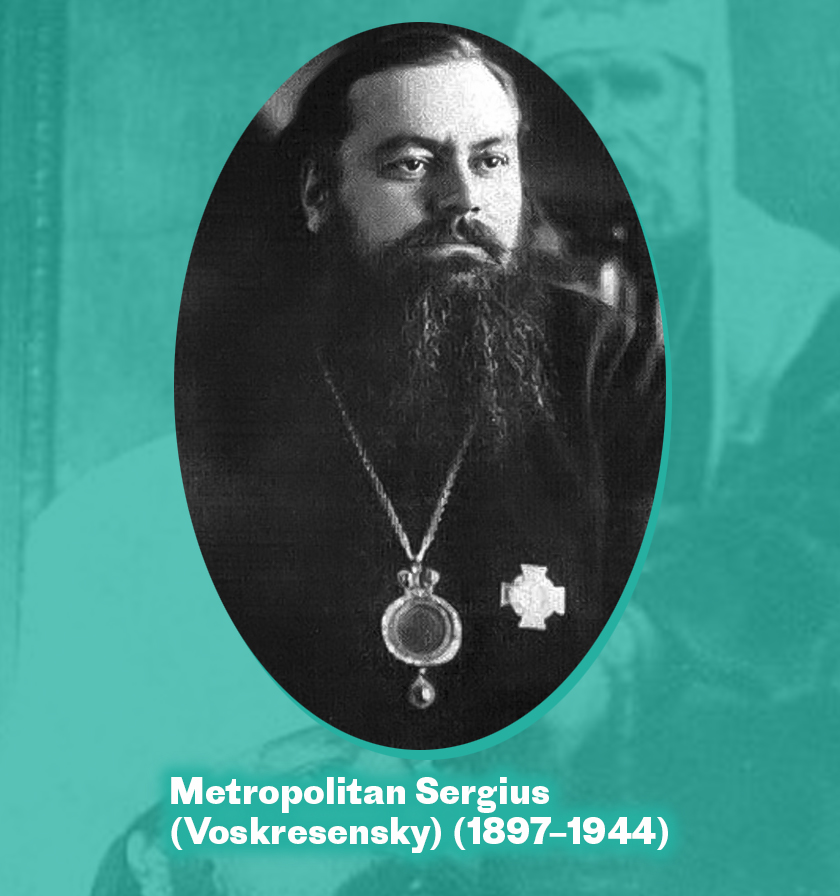

As for the occupancy in 1945 of the see of Tallinn by metropolitan Alexander (Paulus), then in reality it had been canonically vacant since 5th November 1942 when, by decree of the Patriarchal Exarch of the Baltic Countries metropolitan Sergius (Voskresensky), and in essence the decision of the episcopal council of the Exarchate of the Baltic Countries (since the degree was signed by the bishops of Mitau, Narva and Kovno), metropolitan Alexander had been suspended from priestly functions as a result of repeating the schism and dismissed from administering the diocese of Tallinn (with the result that the condition of the 16th Canon which forbids transferring a bishop from his see before his guilt has been ascertained had been fulfilled).

And his fleeing his see in 1944 and the absence of all correspondence with his flock that had remained in Estonia (which would testify to the fact that he looked upon it as his own as before) merely reinforced the widowed status of the diocese according to the same 16th Canon which states: “If any bishop in good standing of honour neither cares to resign nor to pastor his own laity, but, having deserted his own bishopric, has been staying for more than six months in some other region, without being so much as detained by an Imperial rescript, nor even being in service in connection with the liturgies of his own Patriarch, nor, furthermore, being restrained by any severe illness or disease utterly incapacitating him motion to and from his duties — any such bishop … shall be deprived altogether of the honor and office of bishop … and someone else shall be chosen to fill his place in the episcopacy”. Which is precisely what was done.

However, there is something else that gives cause for concern in the interview we are looking at. Metropolitan Stephan would appear to be speaking about martyrdom and expresses sorrow for the path that Estonian Orthodoxy has taken in confessing Christ, for all martyrs and confessors of Orthodoxy in the land of Estonia. And he is quite right to feel this sorrow. But the feeling still stays with me that in his sorrow metropolitan Stephan has surpassed those whom the Lord Jesus Christ denounced for constructing and decorating the tombs of the prophets. At least there we are dealing with the prophets who were killed by the ancestors of those who supposedly venerated the memory of the prophets, whereas metropolitan Stephan, without at all abandoning his abstract veneration of the memory of the confessors in word, for more than a quarter of a century has indirectly denigrated a concrete confessor of the twentieth century, that is, metropolitan Cornelius (Jakobs), who was imprisoned in a labour camp in Mordova, and all of his flock. For metropolitan Stephan we are nothing more than puppets who appeared in Estonia at a time of occupation and as a result of which we remain an instrument of “Russia’s imperial ambitions”. In depicting us in this manner he has at least shown exemplary consistency.

How easy do his praises of the confessors sit with their discreditation as collaborationists. This is what happens when he supports the myth according to which the Moscow Patriarchate is some sort of monster which in 1945 devoured the EAOC, the “true remnant” of which supposedly survived in exile whence it supposedly returned to its place in 1993 (when, in violation of the canons and state laws, our state registered this schismatic structure with its administration at that time located in Stockholm).

Those who have suffered persecution, confessors known and unknown (whom metropolitan Stephan reveres in word) turn out to be, according to this myth, not confessors at all but “invaders from without” who, though, after the schismatics had received their registration, were granted the kindness of receiving all the same rights as long as they agree to a betrayal…

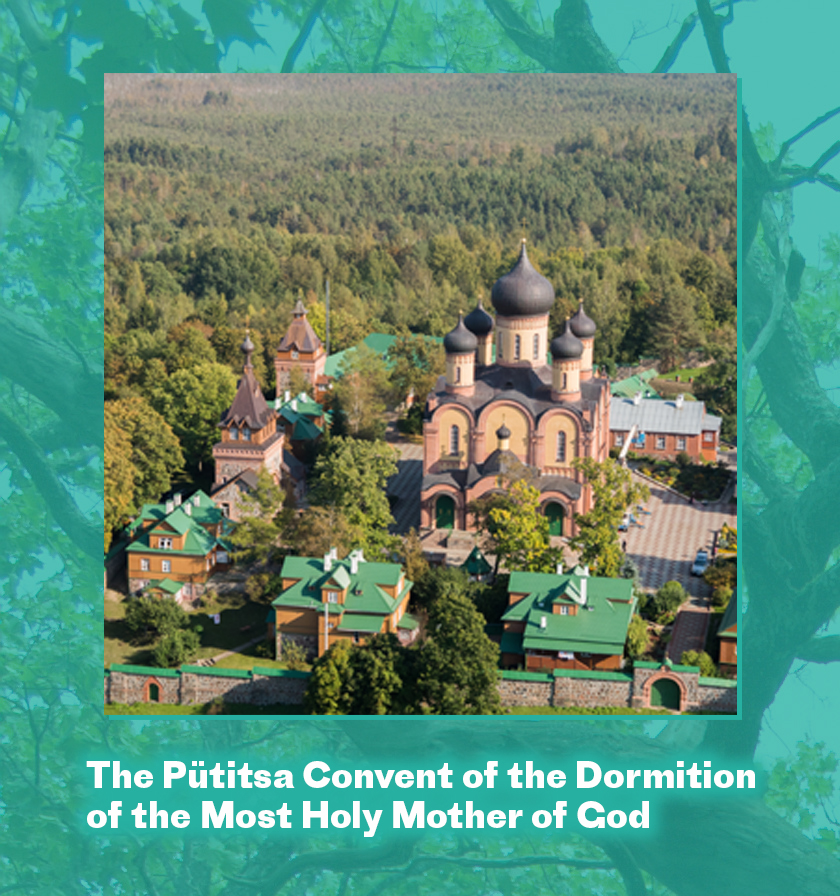

All that had to be done was to agree with their myth and recognize the fact that the Estonian Orthodox Church under the Moscow Patriarchate, which claims to be the EAOC that had not only not ceased to exist but moreover at the Council at Pütitsa Convent on 29th April 1993 had already restored its autonomous status and historical name, is not at all the same EAOC which was transformed into the diocese of Estonia but a creation of the Soviet secret police. This recognition would automatically have proceeded from both means that had been proposed to us of receiving our registration: either become a part of the already registered schismatic (albeit legal) religious organization recognized by the state to be the rightful successor to the EAOC or, since the Mother Church of Russia is so precious, get registered as a newly-formed structure (a sort of remnant of the Soviet occupation) without any right to lay claim to property since nationalized…

We rejected both of these options of either self-condemnation or betrayal. After eight years of legal defeats, the state finally registered our Church in 2002 as a historical and not newly-formed structure but that, as they say, is a different story.

If we look at this part of the interview which His Eminence Metropolitan Stephan gave and, in particular, at his veneration of the path Estonian Orthodoxy has taken in confessing Christ, then we are left with a sense of bewilderment: does he not really understand that the very same people who, thanks to political deceit unfurled by our state officials in the 1990s in tandem with the Patriarchate of Constantinople who now suddenly became merely the tenants of their own church buildings, are the very same confessors and successors who have preserved their faith and looked after these church buildings during the period of atheist persecution in the Soviet Union? It would appear that the head of the substructure of the Patriarchate of Constantinople in Estonia sees as confessors of the faith only those who thought of themselves as being outside of the Moscow Patriarchate and if they were part of the “occupation structure”, then they would break their ties with it at the first opportunity without the slightest regard to their oath before the Cross and Gospel…