“The Third Rome”: From Eschatology to Political Myth

Pavel Kuzenkov, candidate of historical sciences, specialist in Church history and historical chronology. Docent at the history faculty of Moscow State University and Sretensky Theological Seminary, lecturer at Sretensky Theological Academy.

“Moscow – the Third Rome.” This expression is to be heard often in various contexts. Some see in it Russia’s claims to be a world superpower, while others view it as an attempt to ascribe primacy to the Moscow Patriarchate, while others still see in it a link in the continuity between Russian and Byzantium and the latter’s predecessor the Roman empire. But if we investigate the history of this “formula”, we discover that its meaning is far deeper and bears no relation neither to political supremacy, nor, even more so, to any claims to a special status on behalf of the Russian Orthodox Church. The meaning of the “Third Rome” is profoundly mystical and hidden, and it is rooted in biblical eschatology.

The Prophet Daniel and Worldly Kingdoms

The idea of human history as a procession of “worldly kingdoms” begins with the Old Testament Book of Daniel. This book tells of the life and prophecies of St. Daniel, a Hebrew who lived at the time of Babylonian captivity and who served at the court of king Nebuchadnezzar II (605-562 BC) and his heirs.

Among other stories in the Book of Daniel, we find the tale of the prophet’s interpretation of Nebuchadnezzar’s dream of the great statue (Dan 2.1-49). The Babylonian king experienced a strange dream which alarmed him, yet none of the wise men could explain its meaning. And Daniel alone not only could tell Nebuchadnezzar in detail what he had dreamt but also explained its meaning to him: the golden head of the statue made fr om fine gold, its chest and arms of silver, its middle and thighs of bronze, its legs of iron and its feet partly of iron and partly of clay symbolized the kingdoms which would replace each other. And the stone which “without help by human hands” tore away from the mountain and crushed the chaff signifies the kingdom which will be raised up by God and which “will never be destroyed.”

The seventh chapter of the same book speaks of Daniel’s own vision (Dan 7.1-28). The prophet saw four beasts emerging from the stormy sea: a lion with the wings of an eagle, a bear with three fangs, a leopard with four wings and four heads and a great beast with iron teeth and ten horns. Among these horns there grew a new horn which pushed aside the three other horns and had upon it “human eyes and a mouth speaking arrogantly.” Then there sat upon the throne of fiery flames the Ancient of Days in clothing as white as snow, “and the court sat in judgment, and the books were opened.” The terrible beast with the horn that spoke was killed and burnt, while power was taken away from the other beasts. Daniel saw how “one like a human being was coming with the clouds of heaven. And he came to the Ancient of Days and was presented before him. To him was given dominion and glory and kingship, that peoples, nations and languages should serve him. His dominion is an everlasting dominion that shall not pass away, and his kingship is one that shall never be destroyed.”

One of those present explained to Daniel: “As for these four great beasts, four kings shall arise out of the earth. But the holy ones of the Most High shall receive the kingdom and possess the kingdom forever – for ever and ever.”

Daniel’s prophecies evoked lively debate as he had after all foretold the time of Christ’s coming (Dan 9.25-26). The four kingdoms he described fit well into world history: the new Babylonian kingdom (the golden lion) replaced Persia (the silver bear), it was consumed by the kingdom of Macedonia ruled by Alexander the Great, which was divided after his death (the bronze leopard crushed upon the four heads). And then all of the universe was united by the iron embrace of the almighty Roman empire. It was distinguished from all the others by the absence of a ruling ethnos (which explains the lack of similarity to any other beast of the beast which personified it), and the mixture of clay and iron was easily explained as the gradual merger of the militant Romans with the peoples they had subjugated. The horns could be attributed to the emperors’ struggle for power, and the “arrogant mouth” suppressing the “nation of the holy ones” could of course be identified with the advent of the Antichrist, which would then be followed by the kingdom of God.

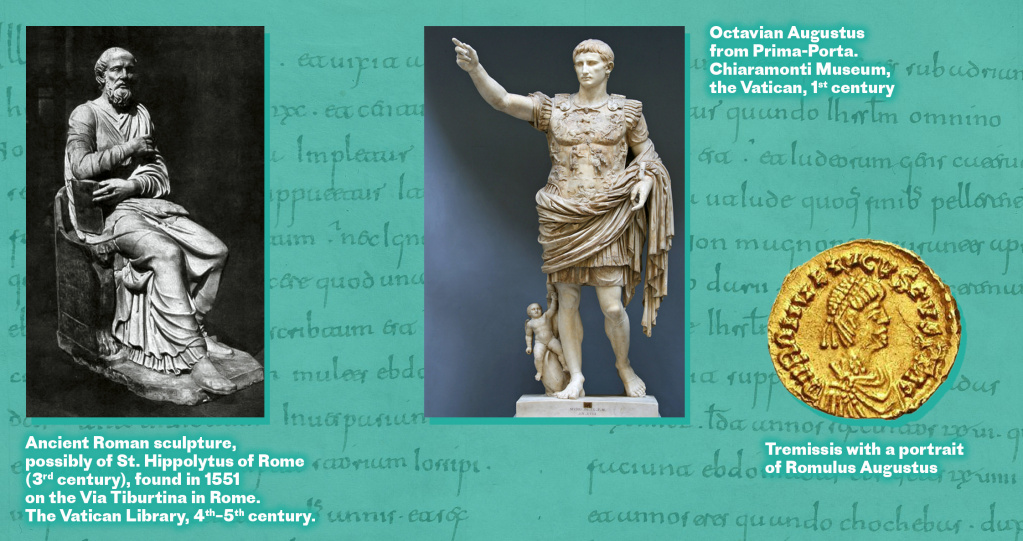

It was precisely this interpretation that St. Hippolytus of Rome (third century) gave to the Book of Daniel, which later gained currency. Interestingly, Hippolytus, who calculated the lengths of the kingdoms which had passed, came to an approximate calculation as how long the Romans actually ruled, that is, five hundred years. It is of note that between the establishment of the empire under Augustus (30 BC) and its fall under Romulus Augustulus (476 AD) there had passed almost the same length of time, that is five hundred and six years. Yet it was only the Western half of the empire that fell. The Eastern Roman empire, which we know as Byzantium, not only remained intact, it existed for almost another thousand years.

Constantinople the New Rome

In 324 AD the first Christian emperor Constantine the Great united under his rule West and East. And almost immediately he commenced the construction of the new capital of the Roman empire Constantinople – the New Rome. He was tasked with taking up the baton of the old Rome as the political centre of the world. Henceforth, the empire had become Christian and its rulers saw themselves merely as the earthly representatives of the heavenly king. In the sacral sphere the state conceded to Christ’s Church, the chief hierarchs of which formed a hierarchy headed by the five most authoritative bishops, the “patriarchs of the oikumene”.

Constantinople still went under its old name of Byzantium and hence our customary use of the name to denote the Eastern Roman empire. But the Byzantines themselves would call themselves “Romans” and were firmly convinced that they still lived in the Roman empire. Which is to say, in the last worldly kingdom which would precede the Second Coming of Christ and the establishment of the eternal kingdom of God. This endowed the Christian empire with a “political programme”: her earthly rulers were to prepare the people under them to meet Christ so that at the Last Judgment they should answer for the moral state of their subjects. This explains why the majority of emperors were so concerned with the issues of religion and showed care for the Church. Indeed, it was upon the purity of dogma and the godliness of the clergy that the well-being of the state and its subjects depended.

Military defeats and internal discord were perceived by the Christian consciousness in their eschatological dimension as tribulations to strengthen Christ’s nation in their fidelity to God. But the position of the state became gradually worse with the passing of the centuries. All of the East from the seventh century onwards found itself under the rule of another religion, Islam. And the West, which found itself under the rule of Germanic Barbarian nations, united itself around the Pope as the sole legitimate Vicar of Christ and broke away from the Greek world, transforming itself in the process from reluctant ally to an irreconcilable rival of Orthodox Byzantium. The New Rome found itself isolated. And when the Greeks, their heads turned by a nascent Hellenic nationalism, rejected their co-religionists the Bulgarians and Serbs, the days of the empire were numbered.

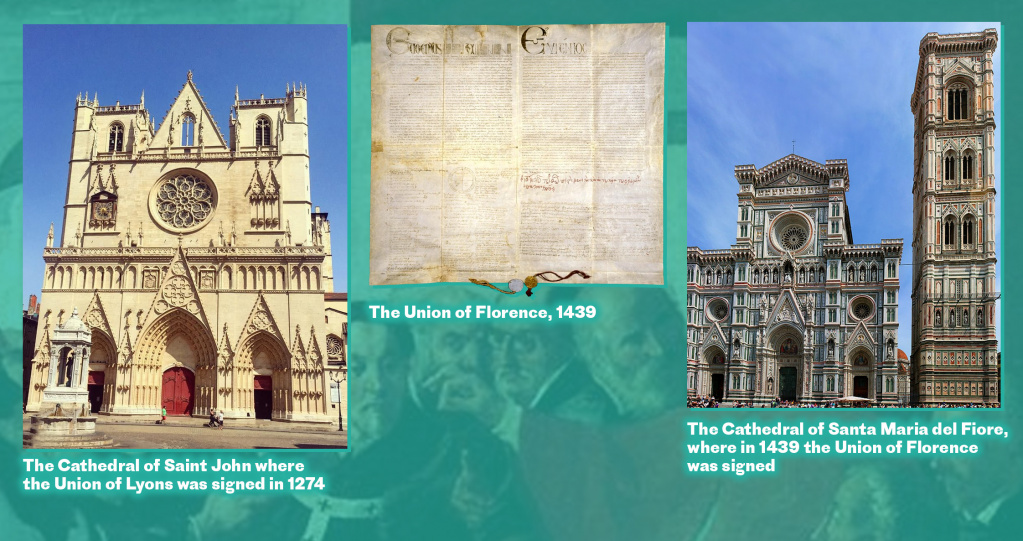

In the desperate hope of preserving the state, the Byzantine emperors and ecclesiastical politicians twice decided to pay homage to the West by accepting the conditions of the Unions of Lyons (1274) and Florence (1439), which had been dictated to it by Rome. But in both instances these ecclesiastical compromises did not only pay the expected external political dividends, but also provoked huge protests within the country.

This is how the Byzantine historian Doukas described the results of the Union of Florence:

“As soon as the bishops disembarked from the trireme, the people of Constantinople gave their customary greeting and asked: ‘How are our affairs? How was the council? Were we victorious?’ The bishops replied: ‘We have sold our faith and exchanged our piety for impiety, betrayed our way of worship and turned out to be Azymites...’ And if one of them asked: ‘Why did you sign?’ They replied: ‘Because we were afraid of the Franks.’ And when they were asked whether they were tortured by the Franks or whether the Franks had killed any of them or thrown any of them in prison, they replied: ‘No.’ ‘Then why did you do it?’ ‘Our hands were compelled to sign,’ they said, ‘as though they had been cut off! Our tongue gave its assent as though it had been cut out of our mouths!’ They could not think of anything better. Indeed, some of the bishops had declared when they signed: ‘We will not sign this until you have given us enough money.’ Money was given and so they dipped their pens in ink. A huge amount of money was expended on them that they gladly took. And then they repented of what they had done but did not return the silver. Having admitted that they had sold their faith, they thereby had committed a greater sin than Judas, for he at least returned the money. The Lord saw all of this and cast them out. Fire was raised up against Jacob and the Lord’s wrath rained down upon Israel” (S. K. Krasavina, ‘Doukas and Sfrandzi on the Union of the Orthodox and Catholic Churches’ (in Russian), Vyzantiisky vremennik, 1973, vol. 27, p.145).

The Elder of Pskov Philopheus and his "formula"

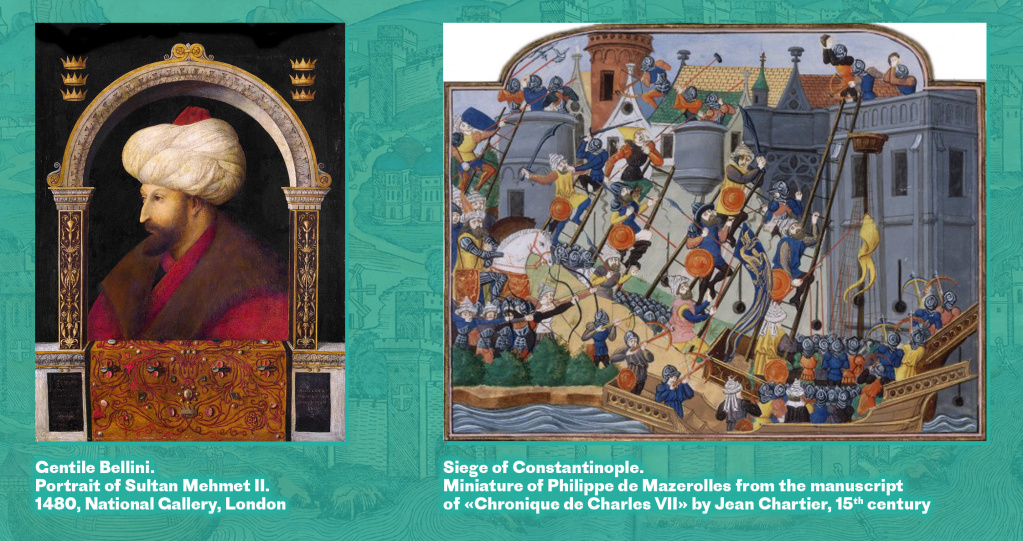

The fall of Byzantium in 1453 was viewed in the eyes of contemporaries as a terrible event which nonetheless had its own logic and was long awaited. Even a significant part of the Byzantine elite admitted that it was “better to see the Turkish fez than the Latin biretta” in Constantinople. And when Mehmed II’s troops entered Constantinople, which defended herself desperately, many people viewed this as deserved retribution for the betrayal of the Orthodox faith.

By the mid-fifteenth century there was not a single Orthodox country left in the world. The New Rome had fallen under the heel of the Turks. Bulgaria, Serbia, Walachia and Moldavia had long been captured by the Ottomans. The last remnants of the Byzantine world, Trebizond and the Crimean principality of Theodoro, fell in 1461 and 1475. There remained only Georgia and Russia. But they, divided into several parts, eked out a pitiful existence under the yoke of Muslim powers. Who then would pick up the fallen banner of the Last Kingdom? Many believed that the fullness of time had come and that the world stood on the verge of the Second Coming, even more so as the 7000th year anniversary of the creation of the world was drawing near.

Yet not all were so apocalyptically inclined in their passive acceptance of the end of the world. Some bishops turned their gazes towards the sole corner of the Orthodox world wh ere the Union of Florence was openly condemned by both the secular authorities and the Church. It was there, to distant Moscow, that there set off in the 1460s the Patriarch of Jerusalem Joachim, who had condemned the naivety of expecting help from the West against the Turks by joining the Union. Joachim died in Crimea without reaching Moscow. But soon after him there would make their way to Russia entire queues of petitioners and intercessors from all over the Christian East. And among Russian thinkers the notion of the special role which Muscovy would play began to gain traction.

In 1472 the Grand Prince of Moscow Ivan III Vasilievich entered into a marriage with Sophia (Zoya), the niece of the last Byzantine emperor Constantine Paleologos. And soon afterwards, in 1480 Muscovite Rus was finally free from paying tribute to the Golden Horde, and from 1493 Ivan III was titled the ‘sovereign of all Russia.’ The 7000th year since the creation of the world, which evoked so much fear, came and went and there began a new millennium dating from the creation of the world which would become an epoch of the rapid growth of a new Orthodox power in the form of the Russian state.

Spiridon-Savva, author of the Letter on the Gifts of Monomachus (c.1503), places in the mouth of the eleventh-century emperor Constantine Monomachus the following exhortation to his grandson, the Russian prince Vladimir Monomakh: “May the Churches of God never know unrest and may all the Orthodox kingdoms abide in peace under the authority of our kingdom and your sovereign autocracy of Great Russia. From this time forth you will be called the God-crowned Tsar, crowned by this imperial crown by the hand of the most holy metropolitan Neophyte and the bishops.”

It is noteworthy that here the emperor does not give his title or his central place as the protector of all the Orthodox world but rather includes it in his service as a Russian prince recognized as the “sovereign and autocratic” tsar of Great Russia.

The most famous text containing the concept of the new mission of the state of Muscovy was the letter, composed in 1523, of the monk of the St. Eleazar Monastery Philopheus to the Muscovite secretary of state Mikhail Misiur Munekhin. At the end of his letter (dedicated to a very relevant topic of the day, which was the refutation of the prophecies of Western astrologers), the learned elder tells his recipient “something of import on the present Orthodox realm of our most radiant and lofty sovereign” (that is, the Grand Prince Vasily III Ivanovich).

“Know, O lover of Christ and God, that all Christian realms have come to an end and have been gathered into a single realm under our sovereign, which is the kingdom of the Romans, according to the prophetic books. For two Romes have fallen and a third exists and there will not be a fourth. The apostle Paul oftentimes recalls Rome in his epistles and this is interpreted as meaning that Rome is all the world. For you see, O elect one of God, how all the Christian realms have been crushed by the infidels and only the realm of our sovereign stands by the grace of Christ. He who reigns should remain steadfast to this with great fear and with turning towards God, not putting his hope in gold and transient riches, but in God who grants all things.”

It is in these last words that we find the true meaning of the “formula of Philopheus”: the burden of the “Third Rome”, the last earthly realm, places upon the Russian ruler a great moral responsibility. Now he has to answer for the whole world and is to rule “with great fear”, putting his hope not in earthly riches but in God’s aid.

In spite of the widespread opinion to the contrary, the Russian grand princes and tsars never laid any claim to the so-called Byzantine legacy. The marriage between Ivan III and Sophia Paleologos, the niece of the last Byzantine emperor Constantine XI Monomachus, had no legal consequences as the heir was Sophia’s brother Andrew, who sold his legacy to the King Charles VIII of France (and then later to Ferdinand of Spain). So, if we are to call Moscow the heir to the Second Rome, then it is only in the sense that it is a spiritual heir and a mystical burden of the “last earthly realm.”

Jeremiah of Constantinople and Patriarchal Rule for the Church of Russia

The concept of the “Third Rome” found no expression in the laws and documents of the Russian state. It is evident that the rulers of Moscow treated the theory with circumspection. Misunderstood, this theory could have been taken to mean a claim to the heritage of Byzantium, which would inevitably have led to a worsening of relations with the Ottoman empire. War with the powerful sultan was not one of the plans of Russia’s rulers, even though their Western “partners’ encouraged them in this direction, as did too many Greeks who dreamt of liberation from the Ottoman yoke.

Surprising though it may be, Philopheus’ formula would be uttered more than once by the Greek bishop the Patriarch of Constantinople Jeremiah II. In the foundation document signed by him in 1589 on the establishment in Russia of a patriarchal throne we hear the following words from the lips of the Greek bishop addressed to Tsar Feodor Ioannovich: “Old Rome fell because of the heresy of Apollinaris; the second Rome, which is Constantinople fell as it was captured by the godless Turks and your Rome, O most pious Tsar is the realm of Russia, the Third Rome which has exceeded all in piety and all beneficent kingdoms have been gathered into one and you alone beneath the heavens are called a Christian emperor throughout out the whole world and Christendom” (Collection of State Documents and Treatises, vol. 2, p.97).

The Idea of the “Third Rome” in the Russian Empire

In the Petrine period of Russian history there was an acute crisis in Russian state ideology. Peter was no lover of Byzantium which had perished, so he believed, as a result of the sanctimoniousness of its rulers and their neglect of military affairs. He chose as his ideal not the second but the first Rome, as witnessed by his adoption of the title of emperor and the establishment of a state senate. And, although the Russian empire as before laid claim to the role of leader in the Orthodox world, this leadership had lost the mystical element of the “last earthly kingdom.” In the nineteenth century the concept of the Third Rome with its original eschatological meaning would seem to have been condemned to oblivion.

But in 1849 at the height of foreign policy successes under Nicholas I, the forty-five-year-old Russian diplomat Fyodor Tyutchev wrote a poem entitled Russian Geography in which he delineates the impressive boundaries of the “Russian realm” and comes to a conclusion clearly parallel to that of the ideas of the elder Philopheus: “Seven inland seas and seven great rivers… From the Nile to the Neva, from the Elba to China, from the Volga to the Euphrates, from the Ganges to the Dunai… here is the realm of Russia and it will abide for all the ages, as foreseen by the Spirit and foretold by the prophet Daniel.”

These hopes of a future imperial greatness were harshly cut short by the Crimean War, even though in the latter the notion of the heritage of Byzantium excited the minds of many Russian commentators and was transformed into the dream of erecting a cross over the Cathedral of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople.

It ought to be admitted, however, that Russian policy was quite pragmatic. The question of taking Constantinople and taking under control the Straits was often on the agenda. Yet behind them were almost exclusively geopolitical and economic interests. The mystical ideas of the Last Kingdom were alien to the empire of the Romanovs, who were orientated towards Westerns models of civilization. It was only under emperor Nicholas II that there was awakened a lively interest in the Byzantine political tradition, but this was a last spark before the disaster of 1917 and the ensuing radical changes in political ideology.

The “Burden of Rome” in the Modern-Day Context

It ought to be noted that the concept of Moscow – the Third Rome has often been seen in the role of a political scarecrow with which European leaders have often terrified their peoples.

It was viewed as particularly vexatious in the eyes of the Greeks, who themselves dreamt of Byzantium’s restoration. The formula of the Old Russian monk was fancifully intertwined by the ideologues of Greek nationalism with ideas of a mythic “pan-Slavism” and they saw in this Russia’s claims to establishing world domination build upon the Slav peoples, which of course would be to the detriment of the Greeks, who saw themselves as the true inheritors of the Second Rome. And, although there was no serious foundation to these fears, many Greek commentators in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries suspected Russia of planning to “usurp” the Byzantine heritage and the Russian Church of driving out the ancient patriarchates.

And yet, the Moscow Patriarchate has never laid claim to the role of “head” of world Orthodoxy. Even under Stalin, during the well-known events from 1945 to 1948, the plans of the Soviet leadership to take world Orthodoxy under the wing of the Russian Church for the purposes of exploiting foreign policy goals found no reflection in the official declarations or acts of the hierarchy of the Russian Orthodox Church, which was well aware of the tragic consequences of such adventurism for pan-Orthodox unity (officials materials for these years can be studied in the archive of the Journal of the Moscow Patriarchy at http://www.jmp.ru/ymarh4354y.php?y=54).

Even more so today there does no exist a single act, document or speech by any representative of the Russian Orthodox Church which expresses even a hint at desiring to subject to itself the sister autocephalous Churches and lord it over them. This fact has been pointed out, as has the irrelevance of the idea of Moscow – the Third Rome, for the modern-day church political situation by the chairmen of the Department of External Church Relations metropolitan Kirill (now the Patriarch of Moscow and All Rus) and metropolitan Hilarion. (See the letter to the metropolitan of Philadelphia Meliton of 23rd December 2004, the interview of 13th July 2019, the interview of 4th December 2020 and the interview of 13th December 2020).

The mirage of the “Slavic threat” has been so powerful that it has even influenced the decision by Greek scholars to no longer use the historical name of the Rusikon (“the Russian monastery”) to refer to the Monastery of St. Panteleimon on Mount Athos. And in his current destructive opposition to the Moscow Patriarchate because of Ukraine the Patriarch of Constantinople Bartholomew and those who think like him are aiming to play the card of “Hellenic solidarity” by insisting that the Greek bishops of the other Local Churches support him in his uncanonical acts.

At the basis of these phobias and suspicions – which, alas, are the determining factor in Constantinople’s destructive policies for world Orthodoxy – lies a complete failure to understand the essence of the idea of Moscow – the Third Rome, which some Greek bishops believe to be “idle talk”, “grossly offensive” and even “blasphemy” (the letter of the general secretary of the Holy Synod of the Patriarchate of Constantinople Meliton, metropolitan of Philadelphia, of 27th May 2004) and even call it a “satanic and imperialistic ideology” (https://www.orthodoxkorea.org/gr-interview-met-ambrosios-russian-orthodox-patriarchate-korea/ , https://www.archons.org/-/moscow-tramples-canons-undermines-korea).

The elder Philopheus, who proposed this formula five hundred years ago, was simply stating a historical reality of the time: the disappearance from the map of the world of all the Orthodox countries apart from Muscovite Russia and the subjugation of all the autocephalous Churches (including the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople) to the authority of infidel rulers. But the most important thing of all is that the concept of the “Last Kingdom” neither then, nor subsequently ever meant Russia’s claim to either the inheritance of Byzantium or, all the more so, to dominating the entire world.

Indeed, the opposite is true: the Third Rome is a mystical image of the “last country” of world history, the rulers of which would bear a lofty moral responsibility for the destinies of all humankind and who ought not to place their hope in the transient riches, power and glory of “this age”, but solely in God.