“In recognizing the fullness of the exceptional competence of Your Most Holy Russian Church…”

1.

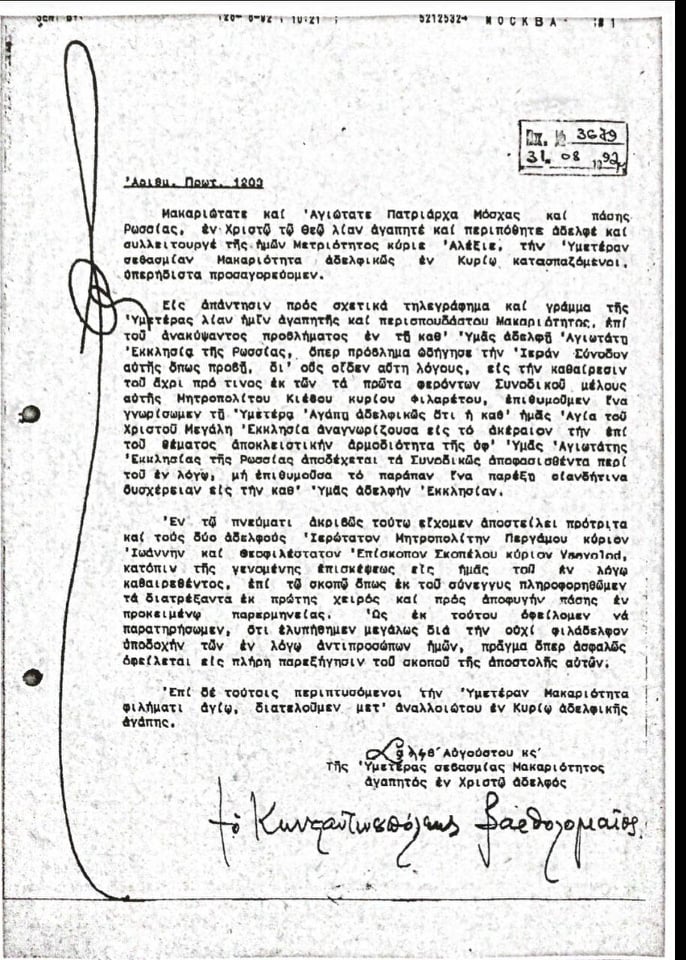

The Declaration of the Holy Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church on the claims by the Patriarchate of Constantinople to the territory of the Russian Church, dated 15th October 2018 (http://patriarchia.ru/db/text/2583708.html, subsequently the Declaration of the Holy Synod) quotes fr om the letter of His Holiness the Patriarch of Constantinople Bartholomew on 26th August 1992 sent to His Holiness Patriarch Alexy in reply to information sent on the ecclesiastical court of the Episcopal Council of the Moscow Patriarchate on 11th June 1992 concerning the deposition of the metropolitan of Kiev Philaret (Denisenko). The original of the letter is kept in the archives of the Department for External Church Relations of the Moscow Patriarchate and is important evidence of the canonical inconsistency of the act of the Holy Synod of the Patriarchate of Constantinople of the 11th October 2018 receiving the deposed and anathematized former metropolitan Philaret (Denisenko) and which recognizes the canonical validity of the “ordinations” performed by him and his followers in the abolished “Kievan Patriarchate”.

Patriarch Bartholomew has repeatedly stated that the most important task of his ministry is the defense of the primacy of the Patriarchal Throne of Constantinople with regard to the other Primates of the Local Orthodox Churches and the privileges linked to this primacy of the Patriarchate of Constantinople. This notion would appear to mean the right to intervene and resolve the dogmatic and canonical controversies which arise in the other Local Orthodox Churches and the sole right to grant autocephalous status to newly-formed Local Churches. Moreover, according to the Patriarchate of Constantinople, only they have the right to organize and administer Orthodox communities in the “diaspora” – that is, in those countries which are not part of the established canonical responsibility of the other Local Churches. Accordingly, the whole world (with the exception of a limited number of countries upon which the jurisdiction of the other Local Orthodox Churches extends) are to come under the direct jurisdiction of the Patriarchate of Constantinople. However, upon these other countries there is also extended the jurisdiction of the ecclesiastical court of the Patriarchate of Constantinople as to it that there belongs the “right to judge throughout the whole Church” (dikaiomata dikastika ti katholou Ecclesia). The Moscow Patriarchate contends this theory and believes the privileges of the Patriarch of Constantinople to be “non-existent”. “These claims, as they are realized today by the Patriarch of Constantinople, have never enjoyed the support of the fullness of the Orthodox Church” (Declaration of the Holy Synod).

2.

The question of appeals and rights of judgment of the Patriarch of Constantinople is one of the most controversial in canonical law. The dispute is marked, inter alia, by differences in the interpretation of a number of canons (the 3rd, 5th canons of the Council of Serdica; the 9th, 17th, and 28th canons of the Fourth Ecumenical Council; the 36th canon of the Council in Trullo). Books and scholarly articles have been written on the topic. Endless discussions could be held on it by propounding arguments for both ‘for’ and ‘against’ from the perspective of church history and by arguing over the consistency of the evidence. It is undoubtedly an important issue for theological and ecclesiastical canonical scholarship. But in the context of the schism in Ukraine arguments on whether Patriarch Bartholomew had the right to receive an appeal by the former metropolitan Philaret are devoid of meaning as there was no appeal on the case of Philaret either in October of 2018 or at any other time.

The aim of this present article is to demonstrate the absolute lack of consistency in the actions of Patriarch Bartholomew in relation to the holy canons of the Church, even in the interpretation in which they are presented in the “theory of extra-jurisdictional privileges” which proposes that the Patriarch of Constantinople in reality does have the right to “receive petitions from bishops and other clergy from al the autocephalous Churches” (Communiqué of the Holy Synod of the Ecumenical Patriarchate on the 11th October 2018 (http://ect-patr.org/nakoinothen-gias-kai-s-synodoy-11-okt-2018).

The archival document allows us with full conviction to state that the topic of Philaret’s appeal was in fact closed by Patriarch Bartholomew as far back as in 1992 when he wrote: “In reply to the corresponding telegrams and the letter of Your Beloved and Esteemed Beatitude regarding the problem that has arisen within the sister Church of Russia which have caused the Holy Synod for well-known reasons to depose the until recently leading member of the Synod the metropolitan of Kiev the Lord Philaret, we desire fraternally to inform Your Holiness that our Holy and Great Church of Christ, in recognizing the fullness of the competence of Your Holy Russian Church in this issue, will take a decision on the level of the Synod on the aforementioned without wishing to create any difficulties for Your Sister Church.” In spite of the fact that judgment of a bishop, even the most senior, is the internal matter of each Local Church, His Holiness Patriarch Alexy II sent official communications on the judicial act of the Episcopal Council to Patriarch Bartholomew and the Patriarchs of Alexandria, Antioch and Jerusalem, as well as to the other Primates of the Local Orthodox Churches. In the Circular Letter of the Eastern Patriarchs (1848) it is stated that there is a custom whereby the Patriarchs of Alexandria, Antioch and Jerusalem “in the instance of unusual and complex matters” “write to the Patriarch of Constantinople for fraternal help,” but “this fraternal aid in the Christian faith is not to be at the expense of the freedom of the Churches of God” (ch.14). Along with the communication from the Moscow Patriarchate, at the same time Patriarch Bartholomew received the appeal from the already deposed metropolitan Philaret. What is more, Philaret after his deposition came to be received by Patriarch Bartholomew, who spoke about this in his letter. Before declaring on behalf of the Holy and Great Church of Christ on agreeing with the decision of the Moscow Council and the recognition of the fullness of the exceptional competence of the Russian Church, Patriarch Bartholomew sent to Kiev the metropolitan of Pergamon John (Zizioulas), a leading theologian and experienced hierarch, and bishop Vsevolod (Kolomytsev-Maidansky), a bishop of the ‘Ukrainian Orthodox Church in the USA’ within the jurisdiction of the Patriarchate of Constantinople. Consequently, his decision to agree with the deposition of Philaret had been weighed up and thought through.

3.

The first provisions regarding the appeal process are contained in the canons of the local Synod of Antioch in Encaeniis, at the Domus Aurea, a huge basilica built in Antioch (6th January 341).

According to these canons, a cleric who has been condemned by his bishop has the right to appeal to the Synod of the bishops of the metropolitanate wh ere he “shall have appeared and made his defense, and, having convinced the synod, shall have received a different sentence” (6th canon). A bishop or cleric who has been deposed by the Synod of bishops is to “submit his case to a greater synod of bishops and to refer to more bishops the things which he thinks right, and to abide by the examination and decision made by them” (12th canon). The sentence agreed upon by the Synod of bishops of a province cannot be the subject of appeal (15th canon). The synods of bishops under the presidency of the metropolitan should be held twice a year and all court cases should be resolved at them (20th canon).

In 343 in Serdica (modern-day Sophia in Bulgaria) there was a Local Synod bringing together the bishops of the Western empire. It was initially proposed to hold an Ecumenical Council there, but the Eastern bishops, infected by the heresy of Arianism, departed and called a synod in Philippopolis. This is why the canons of the synod mention the bishop of Rome Julius, but “that which relates to the pope must be referred to the Patriarch of Constantinople as in different canons he is accorded the same honour as the pope” (Theodore Balsamon, Commentary on the 3rd Canon of the Council of Serdica). In the 3rd, 4th, 5th and 14th canons the fathers of the Council formulated the canonical procedure for appeals which was applied in the instances of the depositions of bishops and other clerics by provincial synods. A bishop or cleric deposed by a synod had the right to appeal to the bishop of Rome and present him with evidence of his innocence. The pope enjoyed the right of being the first to evaluate the justness of the sentence – “if he thinks that the bishops are sufficient for the examination and decision of the matter let him do what shall seem good in his most prudent judgment” (5th canon). “If it cannot be shown that his case is of such a sort as to need a new trial, let the judgment once given not be annulled, but stand good as before” (3rd canon). If, though, the bishop of Rome “be willing to give him a hearing, and think it right to renew the examination of his case, let him be pleased to write to those fellow bishops who are nearest the province that they may examine the particulars with care and accuracy and give their votes on the matter in accordance with the word of truth” (5th canon). In other words, at the instigation of the bishop of Rome the case is returned to be reviewed by the very same synod which pronounced the initial verdict but in an enlarged form. The pope had the right to appoint additional participants of the synod from among the bishops of neighbouring dioceses as well as the right to send his own legates from among the presbyters of Rome. In 1992 Patriarch Bartholomew recognized the legitimacy of Philaret’s deposition and did not consider it necessary to receive officially his appeal and so he recognized the case to be no longer in need of a secondary review.

Moreover, the 4th canon of the Council of Serdica lays down that if a deposed bishop intends to use his right of appeal, his see should remain vacant until the time when the case has been resolved. As is well-known, His Holiness Patriarch Bartholomew recognized the election as primate of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church the Most Metropolitan of Kiev and All Ukraine Vladimir (Sabodan) and in 2014 the Most Blessed Metropolitan of Kiev Onuphrius (Berezovsky). This fact, as well as the fact that Patriarch Bartholomew did not deem it necessary to allow Philaret to appeal officially, testifies that the Patriarch of Constantinople did not recognize at that time Philaret’s case to be in need of a second review.

4.

The fathers of the Fourth Ecumenical Council at its fifteenth session (on 31st October 451) adopted twenty-eight canons, among which two – the 9th and 17th – set out the general order of the court of appeal for the Church in the Eastern Roman empire. The 9th canon states: “If a cleric has a dispute with another cleric, let him not bypass his bishop and go to the secular courts, but let him submit his affair first to his own bishop or, of course, on the advice of his bishop, to some agreed-on third party who can judge the case. If anyone goes against this ruling, let him be subject to canonical penalties. If, on the other hand, a cleric has a dispute with his own bishop or with another bishop, let him appeal to the synod of the province. Finally, if a bishop or a cleric has something against the metropolitan of the province in question, let him appeal either to the exarch of the diocese (ton exarchon tis diokeseos) or to the see of the imperial city of Constantinople, and let him be given justice there.” The 17th canon, which deals with territorial disputes between bishops, repeats this adjunction: “If someone has been wrongfully treated by his metropolitan, let him make an appeal either to the exarch of the diocese or to the see of Constantinople, as has been said earlier.” As the canons of Serdica accorded the bishop of Rome the sole right to receive appeals but not to pronounce a final verdict on appeals, so too the canons of Chalcedon grant to the Patriarch of Constantinople the right to receive appeals for review but do not grant him the right to judge them personally. All court cases were examined at the synods of bishops under the presidency of either the metropolitan of the exarch of a large region, i.e., the patriarch or primate. The archbishop of Antioch Domnus enjoyed the title of exarchos tis dioikeseos tis anatolikis dioikeseos. The Council of Chalcedon legalized the practice of reviewing court cases, including those of appeals, at an endemic synod (synodos endemousa, permanent standing synod of bishops) (see: The 4th act of the Fourth Ecumenical Council on Photius of Tyre and Eustathius of Berytus. https://azbyka.ru/otechnik/pravila/dejanija-vselenskikh-soborov-tom4/1_1_8). The renowned German historian of canon law Karl Josef von Hefele interpreted the concluding sentence of the 9th canon of Chalcedon thus: “The enigmatic part of our canon may be explained in the following meaning: in Constantinople there was always to be found many bishops from various places who went there in order to resolve their disputes before the court of the emperor. The latter would often refer their cases for review by the bishop of Constantinople who, along with those bishops from various provinces permanently present (endemountes), would hold a synodos endemousa.

Indeed, a synodos endemousa under the presidency of the Patriarch of Constantinople as an organ of ecclesiastical jurisprudence has an extra-territorial jurisdiction and judged cases of bishops and clerics from various parts of the Eastern empire. In the post-iconoclast period endemic synods in effect replaced the ecumenical councils, which for well-known historical reasons were impossible to convoke in their earlier form. According to the authoritative Greek historian of canon law Spyros Troianos, “in this form, the synod quickly acquired great importance and replaced the other forms. Gradually, it extended its jurisdiction into the affairs of the other patriarchates, beyond those of the patriarchate of Constantinople. So, in addition to the metropolitans, archbishops and (starting with the ninth century) high-ranking patriarchal officers, others also not infrequently participated in the synod: metropolitans of the other patriarchates, and even patriarchs if they found themselves in the capital. Another factor which contributed to this expansion was that, after the appearance of the Arabs, many bishops of areas of the eastern patriarchates that were occupied by foreigners were unable to take up their positions on their sees and so resided in Constantinople. Canon 18 of the Quinisext Synod, addressing this situation, permits the ‘temporary’ absence of the bishops from their Church. Of course, in certain cases, when a large number of bishops from other patriarchates participated in a synod, it is not easy to distinguish whether it was a second Endousma synod or if it bore more of the character of an extraordinary synod. At any rate, under these circumstances it is not difficult to explain why the Endousma synod took the place of the ecumenical councils as the highest organ of the Church.” It is precisely for this reason that there were invited to participate in the patriarchal endemic synods primates and bishops from other patriarchates, as well as by reason of proximity to the emperor, whose laws and whose power extended widely over all spheres of church life, and that in the late-Byzantine era these synods expressed the voice of the entirety of the imperial Church. But in our time the patriarchal synod of the Patriarchate of Constantinople represents only that particular Local Church. Other bishops or representatives of the other Local Churches are not invited to take part in its work, and for this reason its jurisdiction cannot extend beyond the confines of the Patriarchate of Constantinople Proceeding from the contemporary principle of autocephaly, writes metropolitan John (Zizioulas), “the Orthodox Church in each country is administered by its own synod without any interference from another Church…”

5.

The Russian Orthodox Church rejects the canonical validity of the ordinations and other sacraments performed by Philaret, as well as by his followers from the former ‘Kievan Patriarchate’ who now comprise the majority of the ‘episcopate’ and ‘clergy’ of the so-called Orthodox Church of Ukraine (OCU), including its head ‘metropolitan’ Epiphanius, in being guided by the logic of the judicial acts of the Moscow Episcopal Councils of 1992 and 1997. Philaret was deposed and defrocked and then anathematized. Therefore, his followers too cannot be recognized as being worthy of the grace of the priesthood. The Church can change or abolish these judicial acts with regard to the schismatics by being guided by the principle of economy (leniency) only in the instance of their repentance and willingness to reconcile. This right, however, belongs only to the Episcopal Council of the Local Church from which the schismatic group has fallen away (“Concerning those who have been excommunicated, either among the clergy or the laity, let the sentence that was given by the bishops of each province remain in force; let this be in conformity with the regulation which requires those so excluded by some bishops must not be received by others” [5th canon of the First Ecumenical Council; see also the 32nd Apostolic Canon and the 6th canon of the Synod of Antioch]). “The synod of the Church of Constantinople does not have the canonical right to annul judicial sentences brought by the Episcopal Council of the Russian Orthodox Church” states the aforementioned Declaration of the Holy Synod. In reality, the synod of Constantinople did not even bother to state that these sentences had been “annulled’. The synod simply ignored them as having no importance whatsoever, deeming sufficient reason to “restore” the schismatics to their hierarchical rank merely the fact that they had gone into schism “not for reasons of dogma”. Schism “for reasons of dogma” is called heresy. The Moscow Patriarchate has never accused Philaret or his adherents of heresy. But are not the aggressive schismatic actions which the ‘Kievan Patriarchate’ has carried out not only in Ukraine, but also in Russia and Moldova, that is, within the canonical borders of the Russian Orthodox Church and the various interferences within the confines of the other Local Orthodox Churches of Greece, Serbia and Bulgaria, are they not a grave sin and transgression against the unity of Christ’s Church?

The Patriarchate of Constantinople declares that the purpose of its actions in Ukraine is the overcoming of schism and the realization of church unity. In reality, however, they have led only to a worsening of religious contradictions. Until 2018 the schism bore a mainly regional character. But now division has appeared between the Local Orthodox Churches and within some of them. The actions taken by Constantinople not only violate the principles of the canons upon which the life of the Church has been built for centuries but also clearly contradict the stated aim of “healing the schism”. Firstly, Patriarch Bartholomew has chosen a dictatorial style in relation to the Primate and bishops of the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church in completely ignoring their opinion, beliefs, views and will. Secondly, the Patriarch has forced the canonical bishops to enter against their pastoral and Christian conscience into ecclesiastical communion with and unite into a new ‘Local Church’ with those whom these bishops rightly believe to be unrepentant self-consecrated schismatics who do not have the grace of the priesthood. This stance is based on the judicial resolutions of the Episcopal Council of the Russian Orthodox Church, the legitimacy of which was officially confirmed by the very same Patriarch Bartholomew and has never been recalled.

6.

In conclusion we may formulate a number of theses proceeding from the above.

1. On the basis of the 3rd and 4th canons of the Council of Serdica the documentarily affirmed agreement with the decision of the Episcopal Council of the Moscow Patriarchate and the refusal to receive the appeal by Philaret ought to be deemed official confirmation of the judicial act of the deposition and defrocking of Philaret. If Patriarch Bartholomew in 2018 decided to recognize his decisions to be an error, then he should have in accordance with these canons called for an episcopal council of the Moscow Patriarchate to hold a new trial on this case and appoint, at his wishes, his representatives to take part in this council. Or convoke a Pan-Orthodox Council similar to that which elected the Patriarch of Jerusalem Irenaeus.

2. The Patriarch of Constantinople, as declared in the Communiqué of 11th of November 2018, enjoys the canonical prerogatives of the “Patriarch of Constantinople to receive petitions from bishops and other clergy from all the autocephalous Churches” on the basis of the 9th and 17th canons of the Fourth Ecumenical Council. But only a council under the presidency of the patriarch having corresponding jurisdiction can pronounce judicial sentence on appeals. In the Byzantine era this council was the synodos endemousa, its jurisdiction was recognized throughout the territory of all the empire and was also affirmed by the authority of the emperor. The jurisdiction of the modern-day Patriarchate of Constantinople does not extend to the other Local Churches. What is more, the appeal process is impossible without the presence and evidence of previous judges who had pronounced a sentence of guilt and the agreement with a new decision of the primate of the Local Church to which the condemned belongs.

3. The judicial acts of the Episcopal Councils of 1992 and 1997 continue to have judicial force since they were never annulled in a legitimate way. Patriarch Bartholomew has attempted to force the episcopate of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church to enter into communion with schismatics who do not possess valid ordination and sacraments. Therefore, these actions may be justly qualified as crudely contradicting the holy canons of the Church and going against Christian conscience.

In a letter addressed to the metropolitan of Thessalonica Anastasius St. Leo the Great thus denounced those bishops who lorded it over their brothers: “They who seek their own, not the things which are Jesus Christ’s (Phil. 2.21), easily depart from this law, and finding pleasure rather in domineering over their subjects than in consulting their interests (consulere subditis placet), are swollen with the pride of their position, and thus what was provided to secure harmony ministers to mischief” (Ep. XIV. I. Pl. 54. I. Col.669). Even when dealing with relations between the first (primus) bishop and bishops indirectly subordinate to him by jurisdiction, this relationship should be built upon the foundation of brotherly respect for hierarchical rights, dignity and freedom. It is upon this that the principle of conciliarity is founded. Even more so as delicacy and mutual respect for hierarchical rights are to define the relationships between bishops not bound by the same jurisdiction.

In the modern-day order of the Universal Church as a community of Local Orthodox Churches, the primacy of the Patriarchate of Constantinople could be recognized not only as a titular primacy of honour, but also as a moral primacy of authority based on a natural respect for the ancient canonical tradition of the Church and the one-thousand seven-hundred-year-old history of the Patriarchal see of the city built by the great emperor who is venerated as equal to the apostles. It could be so had not this authority and respect been undermined by the very same present-day Primate of the Church of Constantinople.

***

1. Photiadis Emmanouil, ‘Ex aphoris enos Arthrou’, Orthodoxia, 23, Athens, 1948, p.216

2. Information on the theory of the extra-jurisdictional privileges of the Patriarch of Constantinople is to be found in the article by Alexander G. Dragas entitled ‘The Constantinople and Moscow Divide: Troitsky and Photiades on the Extra-Jurisdictional Rights of the Ecumenical Patriarchate’, Theologia, v. 884 (2017), pp.135-190.

https://www.academia.edu/36576195/The_Constantinople_and_Moscow_Divide_Trotsky_and_Photiadies_on_the...

3. According to the bishop of Christoupolis Macarius, now the bishop of Australia, Philaret in the period from 1992 to 2018 six times appealed to the Patriarch Bartholomew.

(https://www.ukrinform.ua/rubric-society/2561256-episkop-makarios-hristopolskij-pomicnik-patriarha-va....

4. The fourteenth Act of the Fourth Ecumenical Council. J.S. Mansi, Sacrorum conciliorum nova et amplissima collection. Vol. 7, 1762, p.347.

5.Karl Josef von Hefele, A History of the Councils of the Church from the Original Documents, vol.III, Edinburgh, 1883, p.396

6. Spyros Troianos, ‘Byzantine Canon Law to 1100,’ in The History of Byzantine and Eastern Canon Law, edited by Wilfried Hartmenn and Kenneth Pennington, Washington, 2012, p.164

7. John (Zizioulas), metropolitan of Pergamon, Communion as Being. https://predanie.ru/book/121626-bytie-kak-obschenie/#toc43