How the Greek Old Calendarists Became Radicalized and What the Result Has Been

Athanasios Zoitakis, candidate of historical science, lecturer at the Department of Church History (History Faculty of Moscow State University)

In November 1922 Stylianos Gonatas became the prime minister of Greece. A liberal politician, he was a consistent supporter of the modernization and westernization of Greece. In particular, he believed that the renunciation of the Julian calendar would bring Greece closer to Europe, which had long gone over to the new style.

In 1923 the leadership of the church changed. With the support of the authorities the renowned scholar Chrysostomos I (Papadopoulos) became the primate of the Greek Church. Many considered his election to be uncanonical with reference to the 30th Apostolic Canon which stated that “if any bishop obtain possession of a church by the aid of the temporal powers, let him be deposed and excommunicated.”

On 27th December 1923 archbishop Chrysostomos issued a degree on the transfer of the Church of Greece to the new style. He would subsequently regret his decision. He motivated his fatal step by claiming that he had been pressurized by the secular authorities and the patriarch of Constantinople Meletius (Metaxakis): “In vain did I do this… That accursed Meletius had me by the throat!”

Most of the clergy submitted to the innovation, but the people came with processions of the cross out onto the main squares of the cities, calling upon the authorities to cancel this innovation. For this, people were arrested beaten up and even tortured.

In spite of the repressions, many continued to campaign openly for the retention of the ancient Julian calendar (‘old style’), which led to a church schism and the setting up of the so-called ‘True Orthodox Church (Old Calendarist).’

At first, the Old Calendarist movement was spontaneous from 1924 to 1935, but the number of faithful who remained true to the Julian calendar were few. For the first six months of its existence not a single priest took part in the movement, but then there appeared two such clerics.

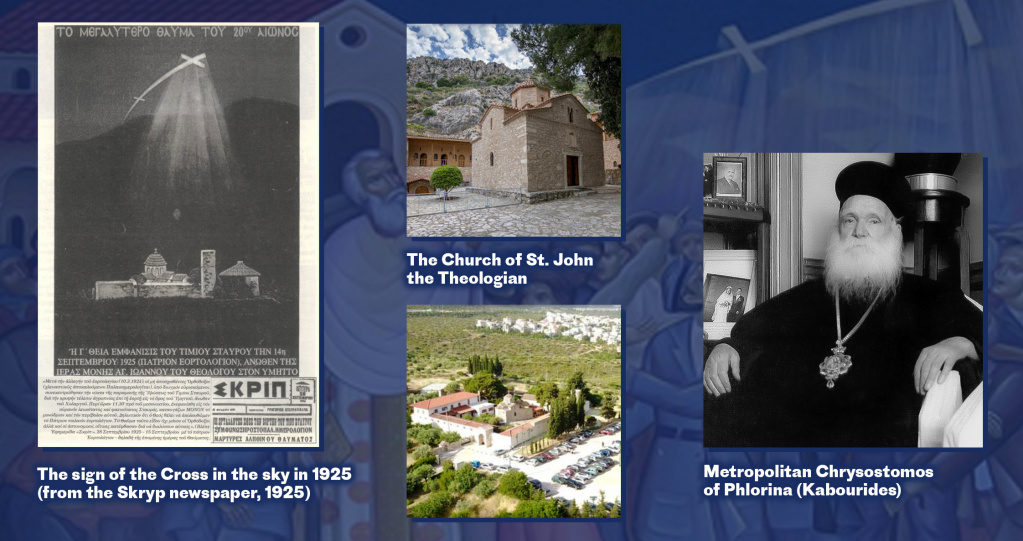

The well-known incident of the appearance of the sign of the Cross in the sky during the all-night vigil before the feast of the Exaltation of the Precious Cross (according to the Julian calendar) in 1925 over the small Old Calendarist Church of St. John the Theologian in Athens led to an increase in the number of adherents to the old style. (The Cross could be observed by both the faithful and the police, who had been sent to break up the prayer meeting, for a full hour).

From 1925 to 1935 there were founded around 800 Old Calendar parishes and periodicals began to be published. In 1931 a parliamentary law temporarily allowed the Old Calendarists to gather freely for liturgical worship. The official Church actively opposed this, and as a result Old Calendar churches were closed and their monks and nuns were expelled from monasteries.

At first, the movement had no bishops of its own, but by 1935 eleven bishops were already sympathetic to the idea of going over to the Old Style. Under pressure from the Greek Church, only three bishops carried their decision into effect, who then began to consecrate other bishops. The movement was headed by the metropolitan of Florina Chrysostomos (Kavuridis). Initially, the aim of the movement was not to set up a new Church; its participants merely wanted to influence the official Church of Greece through the position they had taken. They originally recognized the sacraments also of the new calendarists.

After the Second World War the influence of the Old Calendarists grew. They enjoyed the support of conservative political circles and well-known monarchist politicians regularly participated in events organized by the ‘True Orthodox Christians.’ The Church of Greece voiced its protest against this and called upon the Greek government to ‘chop down the Old Calendarist rebellion’ at its root. In spite of repression enacted by the state, the schismatics continued to gain popularity among the people.

The Old Calendarists’ reputation suffered greatly when in 1952 reports of torture in one of their monasteries appeared. But the main problem for the Old Calendarists were internal conflicts and the radicalization of the movement. In 1937 a group of extremists, headed by bishop Matthew (Karpathakis), broke away from the synod of metropolitan Chrysostomos. Matthew, in contravention of the holy canons, had consecrated a bishop unilaterally. This group refused to recognize the presence of grace in the sacraments of the official Church as well of other schismatic groups.

The Old Calendarists’ reputation suffered greatly when in 1952 reports of torture in one of their monasteries appeared. But the main problem for the Old Calendarists were internal conflicts and the radicalization of the movement. In 1937 a group of extremists, headed by bishop Matthew (Karpathakis), broke away from the synod of metropolitan Chrysostomos. Matthew, in contravention of the holy canons, had consecrated a bishop unilaterally. This group refused to recognize the presence of grace in the sacraments of the official Church as well of other schismatic groups.

After the death of Chrysostomos in 1955 his branch of Old Calendarists were left without a bishop. And then there participated in the consecration of two of its bishops, without the knowledge and permission of the primate and the Synod, two bishops of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia. The Synod of the ROCOR recognized these consecrations only in 1969 and declared their liturgical communion with the followers of the Old Style. But this communion was later broken off by the ROCOR and then restored, but this time with another group of Old Calendarists, the ‘Cyprianites’.

In the period from 1980 to 1990 the Greek Old Calendarist movement endured a time of internal disputes, discord, divisions and the formation of new synods.

The leading role was played by representatives of the radical wing headed by the ‘Matthewites’, who completely rejected the presence of grace in the Local Orthodox Churches. A more moderate position, but also with a negative attitude towards the presence of grace in the official Church, was that of the synod of archbishop Auxentius (1964 – 1985; died 1994).

A third group was organized in 1985 by the metropolitan of Oropos and Fyli Cyprian and the metropolitan of Sardis John. They hold to the opinion that there is of course grace present in the official Church of Greece, but her body has been incapacitated by the heresy of ecumenism and modernism. This is why they reject communion with the official Church, but at the same time they do not claim that they are the sole true Church of in the land of Greece. For these views the more radical Old Calendarists call them ecumenists and traitors.

As a result of the very stringent position of the radical groupings among the Greek Old Calendarists, all of the Old Calendarist movement on the whole remains compromised: by its “zeal not according to knowledge” they have laid a foundation for criticizing all opponents of ecumenism. If we classify the Old Calendarists according to groupings, then we observe an interesting peculiarity in that we can ascribe to each of the three groups not one but several synods (at times there have been between ten and twelve).

The Zealot Schism on Mount Athos

The decision to go over to the new style was provoked by the schism on the Holy Mountain of Athos.

The calendar reform, begun in 1923 by the patriarch of Constantinople, was supported by only one Athonite monastery, that of Vatopedi, but in time it rejected the reform. The Athonite monasteries took the conciliar decision to retain the old style, while at the same time they did not break communion with Constantinople. This decision did not satisfy the radicals who then formed the Zealot movement. The state authorities began to persecute the rebels: the Zealots were expelled from the Holy Mountain and their cells handed over to new inmates. Nevertheless, there are many on Athos to this day who refuse to commemorate the Ecumenical Patriarch. In particular, they control the monastery of Esphigmenou.

Orthodox Traditionalists and the Old Calendarists Movement

Why did the Old Calendarist movement fail to become a mass movement? We can answer this question by turning to the legacy the Greek ascetics of piety who are well-known in Russia. Most of them did not support the transfer to the new style and spoke out against ecumenism, but did not separate from the Church, believing that schism was a far greater calamity.

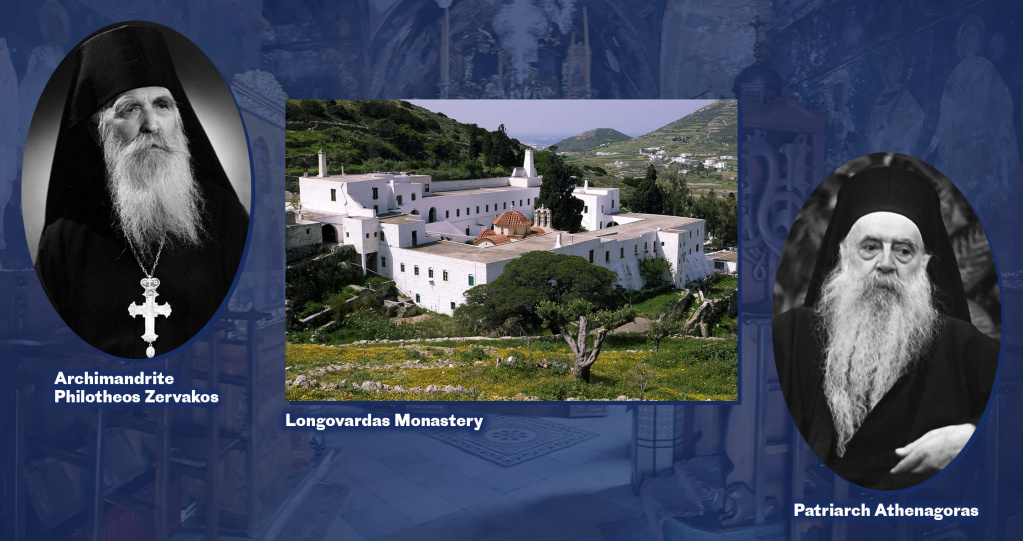

We can find out about these lesser-known pages of history by turning to the legacy of the abbot of the monastery of Longovardas on the island of Paros archimandrite Philotheos (Zervakos) – a renowned Greek father confessor, missionary and theologian. Father Philotheos enjoyed great authority. He corresponded with the patriarchs of Constantinople Meletius and Athenagoras, the primates of many Local Orthodox Churches, the prime ministers and presidents of Greece and the leaders of the Old Calendarist movement. The documents which we publish in this article have hitherto been unfamiliar to the Russian reader.

Zervakos believed that it was essential to observe firmly and with reverence the decisions of the Councils and Holy Tradition. Any distortions in the sphere of dogma were inadmissible, in the sphere of the canons ‘economy’ was possible, but even here it was preferable to adhere to strictness (‘acribea’). Archimandrite Philotheos recognized the authority of the church authorities and treated the church hierarchy with respect, but critically reacted to any distortion of church tradition, even the most insignificant.

Father Philotheos perceived negatively the change in the church calendar. He supported the position of the patriarchs of Alexandria and Antioch, who in 1923 insisted upon the convocation of a Council to settle the calendar issue. At the same time, it has to be noted that the patriarch of Jerusalem was also principally opposed to changes in the calendar.

Let us take a look at the unpublished letter by Father Philotheos of 11th February 1932 in which he speaks of the steps he will take to defend the old style: “I asked the ever-memorable patriarchs of Jerusalem and Alexandria, who rejected the calendar innovations, and they said to me: if you are permitted to keep to the old style, that is good; if they threaten or want to dissolve the monastery, then agree to the new calendar, as this is not a question of dogma. The elders of Athos and my spiritual father advised me to do the same.”

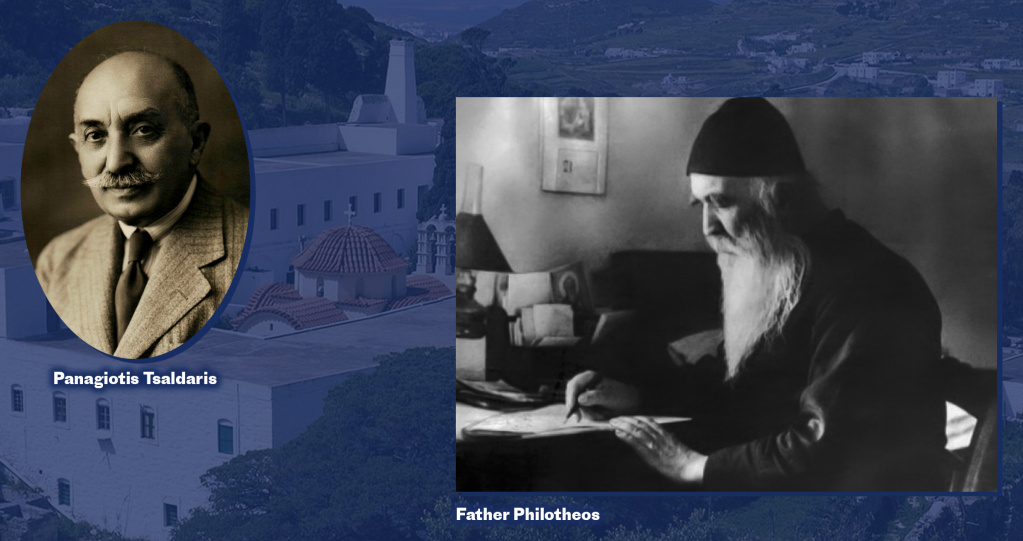

Subsequently, Zevarkos did not give up and for many years continued to fight for the return to the old style. On 20th February 1935 he sent a letter to the Greek prime minister Panagiotis Tsaldaris asking him to enable this return to the old style: “It has been ten years now that the Church of Greece has been in a state of division over the liturgical calendar… I ask you as the ruler of our homeland to ensure that this schism does not become irreversible. Unite the Church which has been so divided by folly… Return the church calendar which has been handed down to us as our legacy by our God-bearing fathers.”

In his letter to the head of state Father Zervakos proposed a compromise: the consecration of an archbishop who would serve on the Old Calendar while at the same time remaining within canonical submission to the Church of Greece. In this way, the Old Calendarists would receive a canonical pastor and their conscience would be pacified.

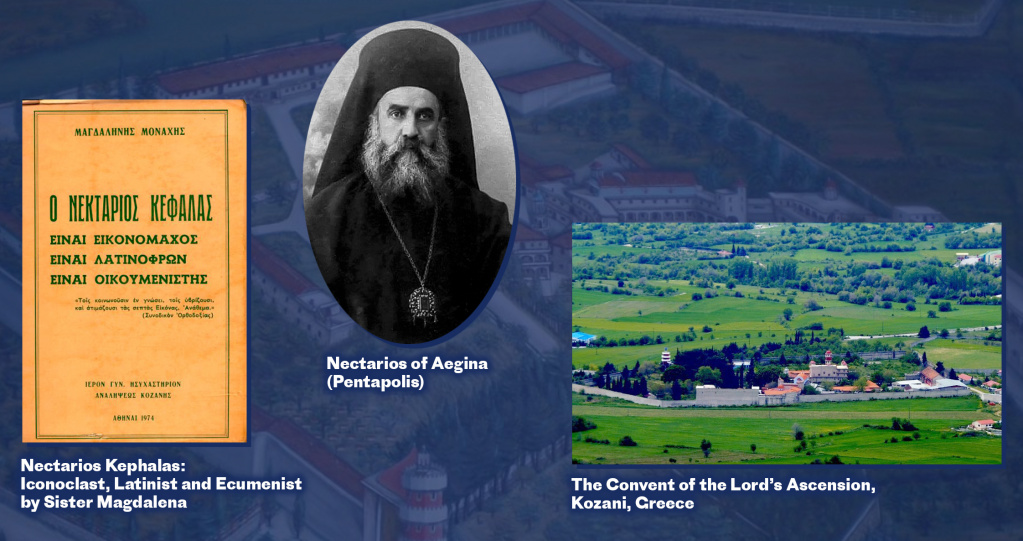

Archimandite Philotheos himself continued to serve according to the Old Calendar right up until January of 1976. The straw that broke the camel’s back was when he got hold of a book published by the abbess of the Old Calendarist convent of the Lord’s Ascension in the town of Kozani by the nun Magdelena.

Magdelena’s book, entitled Nectarios Kethalas: Iconoclast, Latinist and Ecumenist, contained absurd and base accusations laid against the great Greek saint Nectarios of Pentapolis.

Philotheos (Zervakos) attempted to call the nun to repentance and published a book refuting her fantasies. He concluded that it was impossible to be reconciled with the radical schismatics. Archimandrite Philotheos no longer wished to serve on the same calendar as those who believed that the Old Calendar is the only way to paradise while the adherents of the new calendar are on the path to eternal destruction: “The Old Calendarists, in order to retain their calendar, have fallen into many errors worse than those of the new calendarists… They have done away with the first and most important commandment of love, they have divided themselves up into numerous groups, they have begun to rebaptize Orthodox Christians, they have introduced new dogmas and began to worship their calendar… The fanatical zealots believe that the sacraments are invalid and that the Holy Spirit does not descend upon the new calendarists… When looking at the terrible errors of the Old Calendarists, many have chosen the lesser evil and have gone over to the new calendar.”

Father Philotheos was obliged to take the decision to go over to the new calendar (it has to be said that this was not an easy decision for him after many months of fervent prayer and fasting) by the constant schisms among the Old Calendarists: they anathematized each other and rebaptized new adherents who came over to them. Moreover, many bishops were self-consecrated (that is, their consecration was canonically invalid).

***

Today the Church of Greece is not taking anything serious measures to heal the schism. This is because any attempt to become closer to the radical schismatics is hardly possible as they reject the presence of grace in the sacraments of all the Local Orthodox Churches. Whether the return of moderate schismatics to the bosom of the Church will ever happen is a question open to discussion.

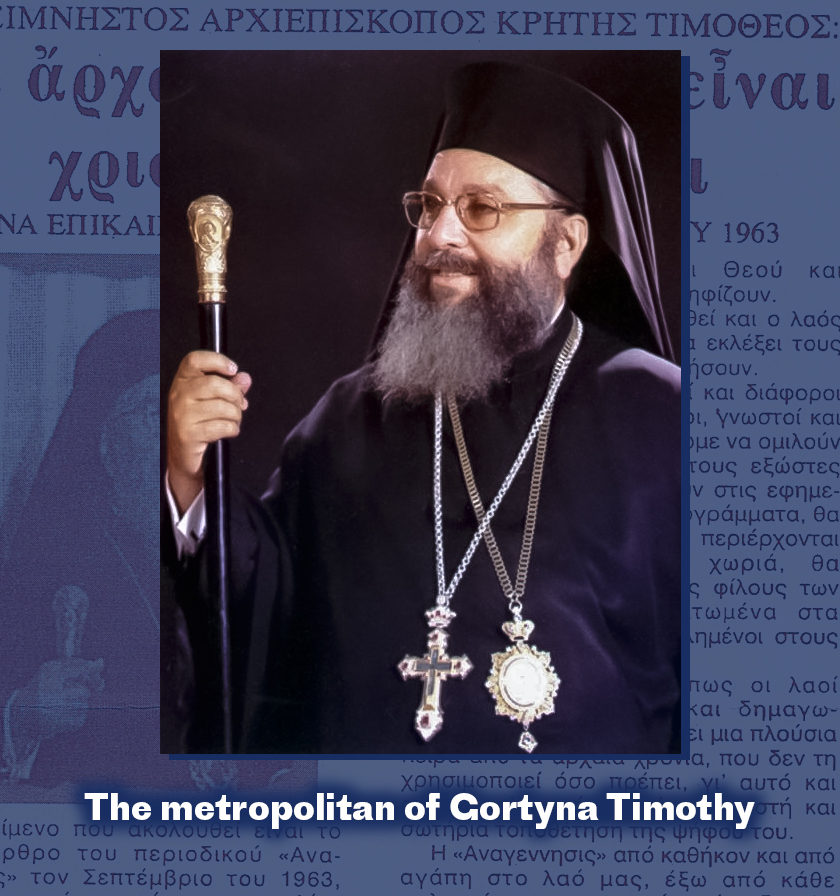

Similar precedents have already taken place in Greece, but happened at a time when alienation between the schismatics and the Church had not yet become irreversible. Above all, we should note the example of the monasteries of Mount Athos and their metochions – all of them worship according to the Old Calendar and yet at the same time are in full communion with the adherents of the new style. Especially successful was the example of the metropolitan of Gortyna Timothy: the bishop initiated negotiations with the Old Calendarists and offered to ordain any priest from the Patriarchate of Jerusalem in order to sustain spiritually their flock – in this way they returned to the bosom of the Church.

Similar precedents have already taken place in Greece, but happened at a time when alienation between the schismatics and the Church had not yet become irreversible. Above all, we should note the example of the monasteries of Mount Athos and their metochions – all of them worship according to the Old Calendar and yet at the same time are in full communion with the adherents of the new style. Especially successful was the example of the metropolitan of Gortyna Timothy: the bishop initiated negotiations with the Old Calendarists and offered to ordain any priest from the Patriarchate of Jerusalem in order to sustain spiritually their flock – in this way they returned to the bosom of the Church.

The schism may be likened to a gradually widening crack: as the years go by it widens ever more and may become irreversible. Often, the removal of the causes of divisions and disagreements does not lead to restoration of communion: old grievances and pride for the schismatics are more important than church unity. Let us hope that the restoration of the unity of the Orthodox Church is still possible, and at present we are to be guided by the words of St. Paisios the Hagiorite: “We are to love the zealot-schismatics, we are to feel their pain, we must never judge them. Most of all, we are to pray that God should enlighten them, and should any of them ever ask for our help in being well-disposed towards us, we can then tell them what we know.”