Are You A Brother To Me Or Not?

Afanasios Zoitakis, candidate of historical science. Lecturer at the department of church history at the History Faculty of Moscow State University.

Afanasios Zoitakis, candidate of historical science. Lecturer at the department of church history at the History Faculty of Moscow State University.

Throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries the Church in many Orthodox countries was under the thumb of the state which aimed to make her part of its bureaucratic apparatus. Parish priests were obliged to fulfill the functions of officials: to register births and marriages, help in compiling the census and in holding elections. And quite often, moreover, church land and valuables were often confiscated and monasteries were close.

The phenomenon known as ‘secularization’ touched upon the Orthodox peoples of the Balkans, that is, the Greeks, Serbs, Romanians and Bulgarians. State policy tied the hands of the Church and seriously curtailed the possibilities for missionary work. One of the Greek hierarchs did not beat around the bush when he declared that “the Church is squirming under the heel of the state… and even in order to sneeze she has to ask permission off some government minister!” Is this not the case that this seems to be what is happening in some countries today?!

The Church’s missionary work practically died out in this period, although there was an acute need for it as society had experience an influx of modern philosophical tendencies and had become rooted in godlessness. The answer to these challenges was the creation of Orthodox brotherhoods – a unique phenomenon in the history of the Orthodox Church. The Christians of the Balkan countries organized themselves into powerful public organizations which for a number of decades had an influence not only upon the Church but also upon affairs of state. It was the Orthodox brotherhoods of Serbia and Greece that had the greatest power. It is they, albeit under different names, who continue to make the history of their countries.

Zoe and other organizations

It was the ‘people’s theologians’ who became the pioneers of the religious renewal – itinerant preachers (laity and monastics) gathered people together in the squares and spoke to them about God and the Church. It was these popular theologians who set up the first Greek Orthodox brotherhoods.

The largest of these was the Zoe (‘Life’) society of brotherhoods, founded in 1907 by the priest Eusebius Matthopoulos (1849 – 1929). Zoe enjoyed its zenith during the time of archimandrite Seraphim Papakostas, who led the organization from 1927 to 1954. Its official periodical Life (Zoe) came out weekly in this period with a print-run of 165 thousand copies. Zoe was distinguished by its genuinely ‘German’ discipline, which allowed the organization to found branches in almost every Greek city and village.

Copied from analogous institutes in England and France, the Greek ‘catechism schools’ were not the invention of Zoe; it was, however, the ‘society of theologians’ which carried out a wide-scale implementation of this idea. Beginning with seven schools in 1926, by 1958 Zoe had under its jurisdiction 2216 schools with 147750 students in Greece and 139 schools with 7747 students on the island of Cyprus.

There were also set up ‘parents’ unions’, a ‘society of Christian mothers’, associations of students, scientific workers, housewives and similar organizations. All of them published periodicals and books in large numbers. A network of printers, libraries and cheap bookshops was extended throughout all of Greece.

Thus, Zoe immediately set to working among various part of society, emphasizing above all social ministry, openness to the world and a conscious endeavour to be close to people with various experiences of life, values and needs.

Zoe sent preachers into the factories and plants and published special educational literature for the workers. The organization’s members went into peoples’ homes and apartments as they preached Christ.

Zoe did not propose any dogmatic or canonical innovations, even though certain aspects of Orthodox tradition were subject to revision by the organization. This manifested itself in its relationship with monasticism. Zoe’s headquarters were located in the centre of Athens and its top floors were occupied by ‘modern’ monks who observed all three monastic vows of poverty, chastity and obedience but who did not wear monastic garb. The organization believed that the life of a monk ought to be orientated towards mission. Prayer was viewed as an inadequate form for a monk to minister to the world, so the need for practical mission and material offerings to the human race was declared.

Another pillar of Zoe’s programme was liturgical reform and it proposed a number of innovations. For Zoe, preaching in effect became the heart of liturgical worship, while prayer occupied a secondary place. What is more, the need to sit during worship was affirmed so that people could concentrate their attention and the so-called ‘secret prayers’ of the priest were, it was suggested, to be read aloud.

Zoe considered moral behaviour to be the cornerstone of society. The organization’s members were to serve as an example of the loftiest and most decent persons, which would be manifested in their external appearance: there was a strict dress-code, control over their gestures and gait and the way they talked.

As a result of internal disagreements, forty five of the 135 members of the brotherhood left Zoe and some time later formed a society by the name of Sotir (‘The Saviour’). Towards the end of the 1950s there were already dozens of such brotherhoods in Greece (‘Orthodox Christian Unions’, ‘Redemption’, ‘Three Holy Hierarchs’, and so on). In spite of some differences in their ideology and structure or a greater or lesser degree of traditionalism and radicalism, they on the whole were all constructed on a similar basis.

Non-Church brotherhoods – a blind alley or the path to renewal?

The Greek Orthodox brotherhoods were often labelled ‘non-Church organizations’. Their founders proceeded from the best motives and wanted to ‘renew Orthodoxy and cleanse the Church’. So why then, in spite of this, did their opponents stick the label of ‘non-Church’ upon them? The representatives of the brotherhoods themselves were partly to blame. The societies existed as being registered by the state as secular associations. This was a logical choice as the brotherhood’s members wanted to be autonomous from the bishops and from the parochial clergy. Subsequently, clergy and laity were divided into ‘ours’ and ‘not ours’ when belonging to the brotherhood became the criterion of ‘progressiveness’ for a particular priest.

The pathos of ‘transforming’ the Church, the educational system, culture and even political circles began to occupy an important place in the organization’s rhetoric. For these aims political works were considered to be the best genre. A great part of the independent works of the theologians from Zoe were books written against something or someone, whether it was the masons, ecumenism, heresies, prejudices and even the Olympic games. The members of the brotherhoods became implacable enemies of communism, which they viewed as a moral threat.

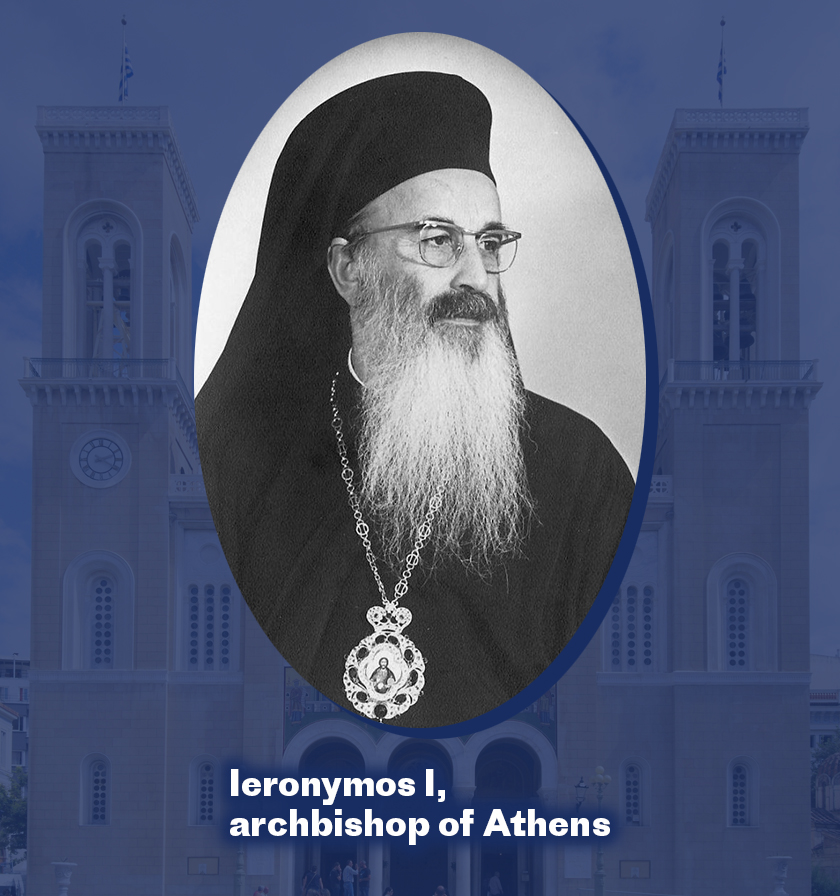

The ideologization of the movement ensured its promotion to the forefront of Greek politics, and subsequently led to the disintegration and collapse of the organization. In 1967 members of Zoe already comprised the leadership of the hierarch of the Greek Church: the archbishop of Athens was the longstanding leader of Zoe Ieronymos (Kotsonis) and the bishops were also notable faces within the organization. A reform programme was begun, inspired by the spirit and ideals of the ‘brotherhood of theologians’. Along with the state authorities (the dictatorship of the so-called ‘Black Colonels’), the hierarchy of the Church implemented a broad programme for the improvement of the ‘moral climate’ of Greece and a special type of citizen – the ‘Greek Christian’ – was created. (Files on Greek schoolchildren detailing their ‘spiritual and physical health’ say a lot about the spirit of the measures that were carried out.)

The popularity of the brotherhoods among the people undoubtedly testified to the fact that Orthodoxy had remained the nucleus of the way Greeks perceived life throughout the twentieth century. In spite of individual instances of controversy in the ideology and practice of the movement, the Zoe brotherhood remained a community of engaged radicals who tried to ensure that Orthodoxy would become the heritage and faith of everyone. The active missionary work of Zoe enabled the birth of a new generation of people who would take an interest in the life of the Church.

Young men who had become disillusioned with the ideals of secular organizations breathed new life into Greek monasticism. The members of Zoe Vasileos Gondikakis and Gregorios Khadziemmanuil abandoned the organization in 1966 and headed for the Holy Mountain of Athos where they inspired the rebirth of the monastic houses of Stavronikita and Iberia. The monastic fraternity was added to by former members of Zoe under the guidance of archimandrites Emilianos (Vathidis) and Georgios (Kapsanis) who had revived the empty Athonite monasteries of Simonopetra and Gregoriou.

The peasant revival

At the beginning of the twentieth century there began to appear in Serbia people who were markedly distinguished by their religiosity. These were mainly peasants who preached the Gospel and were noted for the purity of their lifestyles. They always attended divine services, regularly went to confession and took communion, loved to visit holy places and often went on processions of the cross. These people were soon to be known popularly as ‘the pilgrims’, ‘the pious’ or ‘the evangelizers’.

The seeds of the pilgrimage movement appeared in the latter half of the nineteenth century and initially remained confined to a small number of Serbs. Various groups of pilgrims arose spontaneously in different parts of the country without communicating with each other and without informing each other of their activities.

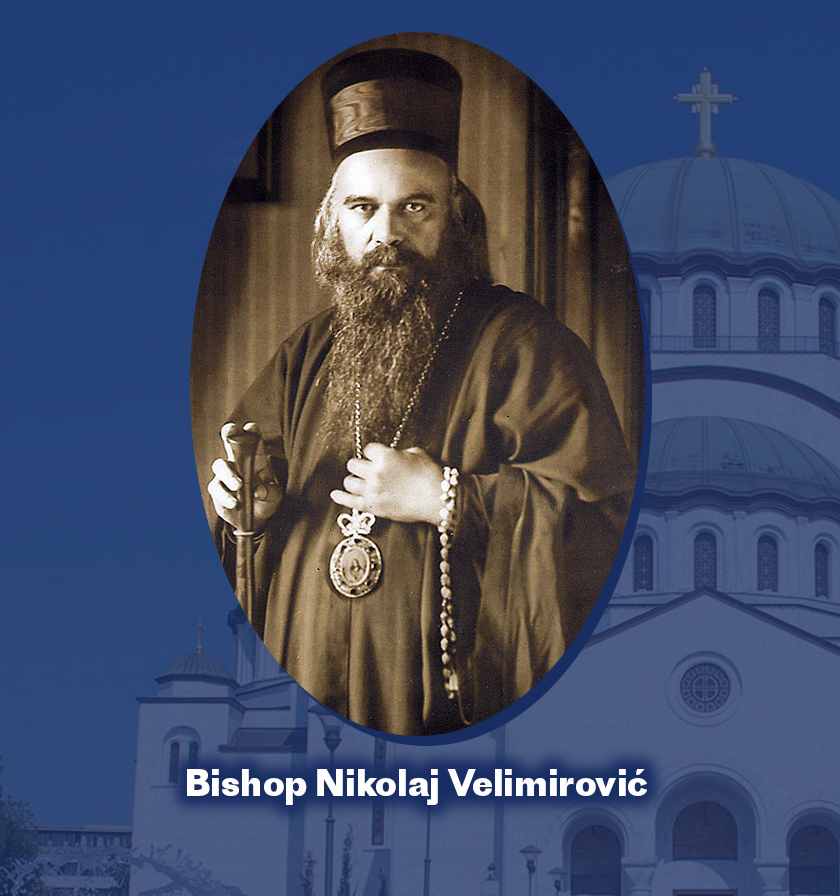

The man who was capable of consolidating these disparate groups into a single organization called the Orthodox Popular Christian Association (established in 1920) was the renowned missionary and writer bishop Nikolaj Velimirović. It is thanks to him that the attitude among bishops and priests towards the pilgrimage brotherhoods changed significantly.

“Try to understand the pilgrims. Refrain from casting stones at them as you may inadvertently cast a stone at Christ. Do not reject them, and they will not reject you,” wrote bishop Nikolaj.

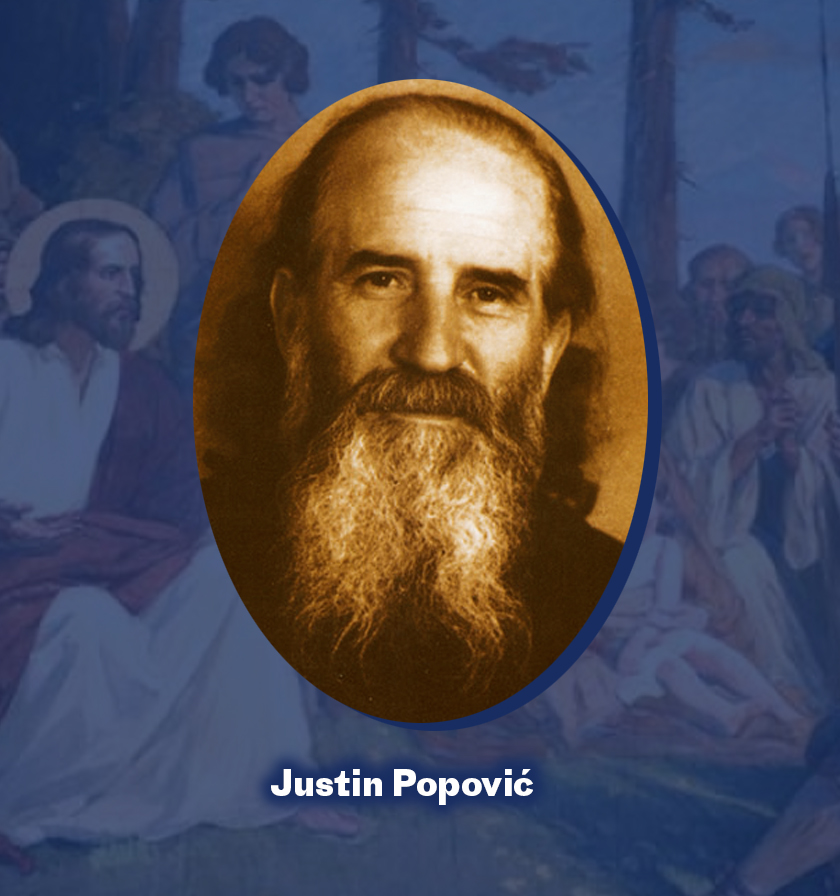

Contemporaries noted the main distinguishing feature of the pilgrimage movement which was its adherence to Church life as its participants had no desire to create a separate sect. The renowned Serbian religious author Justin Popović wrote: “This movement is a movement of spiritual heroism among the masses. True pilgrims strive to accomplish individual spiritual feats; this is especially important with regards to prayer and fasting… It is in this that they are specifically of Christ and specifically Orthodox…”

We know of the pilgrims’ way of life thanks to the numerous testimonies of contemporaries writing in periodicals. The pilgrims “simply enjoy being in the Church – it is never too long for them and it is always sweet.” “When they speak among themselves it seems as though they are conversing in some sacred angelic language because they speak only on sacred topics, while they speak of earthly things only in as far as it is necessary.” “Their life at home bears the imprint of permanent sanctity. Foul language or curses never trip off their lips.” “The pilgrims are the most cultured part of our people… From their love of Scripture they have all learnt to read it precisely and well practically of their own accord.”

The pilgrims were strikingly different from other layers of society not only through their lifestyle, but also by their external appearance. Thus, the pilgrim-missionary was often described as an old man in folk costume with a long bear and hair who would walk barefoot.

The pilgrims wore pectoral crosses and the women headscarves, which had ceased to be a tradition during the five-hundred-year-long Ottoman rule.

With the setting up in 1920 of the official organization of pilgrims it became easier to identify them since now not everybody could call themselves a pilgrim, but only a member of the Orthodox Popular Christian Association.

Each member of the Association was accorded certain obligations reflecting all of the community’s striving for asceticism and prayer. People became pilgrims from various layers of Serbian society, but the overwhelming majority of them remained peasants.

There were regular congresses of the pilgrim movement. These gatherings, as a rule, took placed annually and were viewed as special places of prayer and decision-making for the future of the brotherhood.

Apart from publishing and the opening of reading rooms, the pilgrimage movement undertook active missionary work. This led to a growth in the number of brotherhoods organized in Serbia.

Like the Greek brotherhoods, the Serbian counterparts often engaged in charity work. They organized missionary foundations for the poor, the sick, orphans and widows. They opened courses for bee-keepers and weavers. The pilgrims cared for the sick and visited prisoners.

It is noteworthy that the pilgrims actively observed the work of the Greek Orthodox brotherhoods and considered their Greek confreres to be of one mind with them.

On 28th and 29th August 1933 there was a pilgrimage congress in the Kovilj monastery. It was attended by bishops and the head of the Serbian Church Patriarch Barnabas. The congress was the largest in the history of the movement – more than 5000 thousand people from all over the country converged on the monastery on the appointed day. The report of the Orthodox Popular Christians Association which was examined at the congress in Kovilj spoke about the compilers’ belief in the movement’s success: “The Church was full every Sunday and even more so on feast days. Consequently, we draw the conclusion that godliness within our country is increasing thanks to our movement…”

In 1939 approximately 450 brotherhoods throughout the country were registered at the headquarters of the Orthodox Popular Christian Association, while the print-run of the pilgrims’ journal The Missionary ran to 150 thousand copies. The number of pilgrims exceeded 200 thousand people. An ever-increasing number of priests took part in the work of the brotherhoods and took them under their wing.

Unfortunately, the incipient Second World War did not allow the movement to develop and consolidate the success which it had prior to the 1940s. Part of the reason for this was the position of some pilgrims who were politically active and supported radical anti-communist forces.

The pilgrimage movement could no longer continue its missionary activities in postwar Yugoslavia. The atheist authorities forbad the Church’s representatives from engaging in missionary work. Nonetheless, it was the pilgrimage brotherhoods which became the spiritual leaven allowing the Serbian Church to survive the many years of state interdictions and repression. In the initial postwar years all candidates for the Serbian theological seminaries emerged from the families of members of this movement. The same may be said of the novices in the monasteries, especially of the new inmates of the convents.

After the Second World War there existed a number of pilgrimage brotherhoods, but as a result of the limitations placed upon them by the state their activities could not be considered equal to those of the pre-war movement. The one thing that remained unchanged was the personal piety of these people that had become a fount sustaining the Church of Serbia after the war.

***

Religious maximalism was characteristic of both the Greek and Serbian brothers, as well as a strong desire to observe the divine commandments.

The Greek and Serbian brotherhoods preached Christ in both oral and written form. They visited the cities and villages, published literature, set up missionary courses and Sunday schools and opened reading rooms.

The brothers engaged in charity work in rendering much aid to prisoners, the elderly and orphans.

And today?

In Greece there exist to this day Orthodox brotherhoods, while in Serbia the heirs of the pilgrimage movement continue their activities. But their renown and influence cannot be compared to that of their powerful predecessors.

In recent years, however, the Orthodox brotherhoods around the Serbian Church have begun to strengthen their position. This has come about as a result of the strong political pressure exerted on the Orthodox Church. This concerns too the situation in Kosovo and the recent events in Montenegro.

In Russia the phenomenon of Orthodox brotherhoods has also become widespread. Yet they have not attained the same position of might as those in the Balkan countries (especially those which existed before the Revolution of 1917). In terms of influence and scale the Russian Orthodox brotherhoods of the nineteenth century cannot simply be compared to their Balkan counterparts.