The Canopy of Hitler

Hitler and a new religion for the Eastern Slavs

By Michael Shkarovsky, PhD, Leading Researcher and Chief Archivist of the Central State Archives of St. Petersburg, Lecturer at the St. Petersburg State Institute of Culture, Professor of the St. Petersburg Theological Academy

In undertaking an attack on the USSR, the Nazi planned to trade actively on religion. They already had a rich experience of using this policy in both Germany and the territories they had captured in Europe. The methods and practices of the Nazi’s church policy were tested before 1941 in various European countries they had subjugated and extended to religious organizations in the Soviet Union. In addition, this policy here was defined largely by their overall negative attitude to the Slavs, in particular Russians. At the same time, the policy of Nazi Germany concerning Orthodox Churches, primarily the Russian Church, was considerably evolving to be divided into two different stages: before June 1941 and after.

There were many factors defining the stand taken by German departments in this matter, i.e. propagandistic, ideological, military (the situation on the Eastern front), international, etc. For all the difference of these positions, the decisive role was played by directions of the Nazi Party leaders and personally Hitler, which makes it possible to speak of the existence of a guiding line.

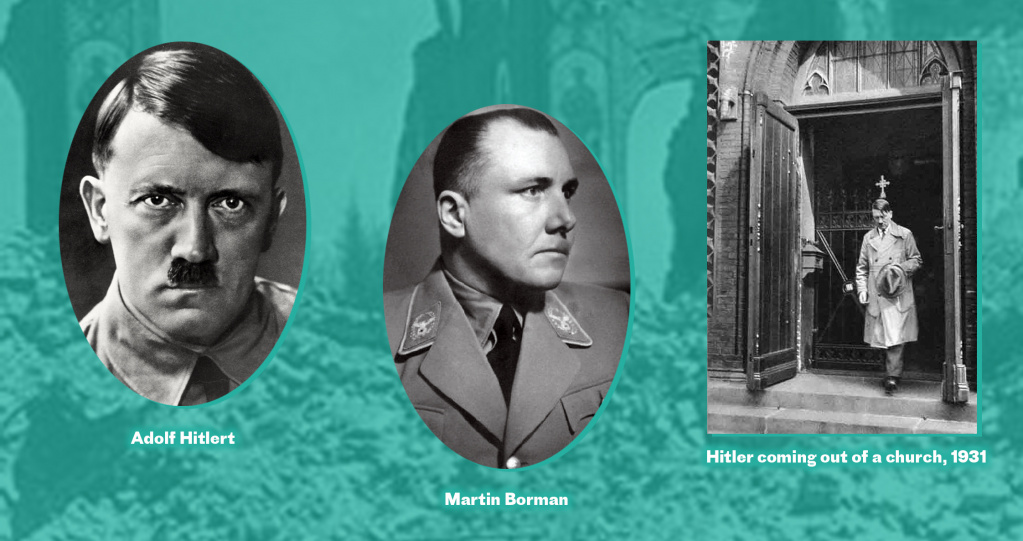

There were several German governmental organizations engaged in the affairs of the Russian Church. The severity of their attitude can be classified as follows: the softest one was shown by the Reich Ministry for Church Affairs, then after it by the Wehrmacht High Command and the Military administration in Russia to be followed by the Reichskommissariats of the occupied Eastern territories (PMO), which was to make with time some concessions to Orthodox Churches; much more severe was the the Reich Main Security Office (RSHA), and the openly hostile was the attitude of the Nazi Party leaders - head of the Nazi Party Chancellery M. Borman and A. Hitler himself.

At the first stage, the German departments (mainly the Reich Ministry for Church Affairs) gave some protection to the Russian Church Abroad by pursuing a purposeful policy of the unification of the Orthodox diaspora in the Third Reich. The campaign launched with this aim was calculated for an international propaganda effect. The Nazi regime wished to appear in the public eyes as an antipode of the Soviet government, which precisely in the 1930s was the most active in persecuting the Russian Church. In addition, the aims were also to soften the ill effects of reports appearing abroad about a launched persecution against the Lutheran and the Catholic Churches and to win the favour of the Balkan states - Bulgaria, Romania, Greece and Yugoslavia populated with Orthodox Christians.

With time the Reich Ministry for Church Affairs also started pursuing its aim not shared by other departments, i.e. the creation of an independent national German Orthodox Church.

After the beginning of the Reich’s military aggression in the Balkans in early spring 1941 and against the USSR in July, the previous policy underwent a great change (the first signs of these changes were already visible in the Polish General Government in 1939-1940). The negative attitude to the Russian Orthodox Church prevailed. It became subject to even reinforced methods of pressure that had been already tested in relations to other confessions within Germany itself where the guiding line in solving ‘the religious problem’ was directed towards the destruction, internal and external, of the established traditional stable structures, i.e. the ‘atomization’ of Churches. There were also attempts to break the Russian Church into several unconnected parts (mainly ethnic ones) and to put these parts under full control and, in doing so, to use church organizations for assistance to the administrations of occupied territories and for propaganda. It also affected the attitude to émigré Russian clergy as these administrations sought to isolate them fully from events in Russia and from war-prisoners and Russians brought to Germany for labour.

Since July 1941, the problem of Orthodox Churches fell into the sphere of interests of the major Nazi departments, i.e. the Party Chancellery, Main Security Office, Reich Ministries for the Occupied Eastern Territories and Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The Reich Ministry for Church Affairs was ‘pushed into the background’ as it was not altogether let into the occupied territories in the USSR. In case of a military victory of the Third Reich, the Orthodox Church would have had to encounter a new, third stage of the Nazi church policy. In the RSHA and the Party Chancellery, plans were developed to gradually liquidate this Church and create a new religion for occupied Eastern territories.

Given the initial entire external difference between the Nazi and the pre-war Soviet religious policy (1920-1930), they had much in common. It is quite evident from the example of Warthengau (Pozan region), which was chosen in 1939 as a ‘proving ground’ for Nazi church experiments. Just as in the USSR, the monasteries were closed there, and all the religious activity was reduced to the activity of communities.

Since the beginning of the war in the USSR, the Nazi decided to allow small indulgences to the Orthodox faithful in the occupied territories. It is stated in some instructions that the religious activity of the local population should not be obstructed but nothing is encouraged either. There was even a draft law on freedom of religious activity in the East, which was never adopted though. It is likely that it was too much for Hitler to sign this law because of his inner anti-Christian position, not only because of the Nazi’s fear that this decree would make a negative impact on the Church in German itself. The real religious policy of the German occupational administration also had much in common with the pre-war Soviet policy. In his order of 16 August 1941, RSHA head Heydrich ordered the security police and SS units to keep reporting about developments in the church sphere in the occupied part of the USSR.

One of the peculiarities of the Nazi religious policy lies in the fact that, unlike Soviet figures, all the leaders of the Third Reich were mystically, pseudo-religiously oriented and gave an apparent attention to this aspect. Since the end of the 1930s, they also developed plans for creating ‘a new religion’. One of these plans, probably obtained by the American intelligence, is mentioned in an official statement made by President Roosevelt in the end of 1941. Roughly in 1939, another detailed, stage-by-stage ‘Plan of National-Socialist Religious Policy’ was developed by Reichsleiter Rosenberg’s service. It stated the need to establish in 25-years-time a Nazi state religion obligatory for each citizens. Thus, if this plan had been implemented, traditional confessions would have awaited a sad fate.

Already in August 1941, two months after the beginning of war with the USSR, a basic guiding line for the church issue in the East was developed in compliance with Hitler’s instructions. The German government bodies were only to tolerate the Russian Church while promoting its maximum possible fragmentation into separated trends in order to avoid a possible consolidation of ‘leading elements’ for a struggle against the Reich. It also contained the tasks to use Orthodoxy for propaganda purposes as a spiritual force persecuted by the Soviet power and potentially hostile to Bolshevism and to use church organizations for assisting the German administration in occupied territories.

Hitler’s directions to prohibit the Wehrmacht military from assisting in any way the rebirth of church life in the East were not accidental. In the second past of 1941, some officers and the German military administration officials helped to open churches. A single decree proved to be insufficient for putting an end to such facts and in September, apparently worried by this, Hitler issued additional instructions. They were published together with the previous four directives on 2 October 1941 in the form of orders from the commanders of back areas in the North, Center and South army groups. Soon after additional instructions of the military leadership followed to explain to the troops the position to be taken with regard to the Orthodox Church. Gradually, though not at once, these orders made their impact and every kind of help to the Church from German troops was stopped.

In the first months of war with the USSR, using the fact that the civic administration had not yet been formed in the occupied territory, the police security bodies and the SS tried to gain prevailing influence on religious organizations. The views of the security police and those of the Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories did not coincide in everything. Thus, the RSHA began developing long-run post-war plans of the religious policy in the East. Already on October 31, 1941, an appropriate secret directive signed by Heydrich was issued. The total racism of this order leaves no doubt as to the fate of Orthodoxy in case of Hitlerite Germany’s victory. It would begin to be destroyed and a ‘new religion’ deprived of many basic Christian dogmata would be propagated.

The Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories was not engaged in such plans. It sought to resolve tasks that are more concrete: the ‘appeasement’ of occupied territories, exploitation of their production potential in the interests of the Third Reich, securing the local population’s support for the German administration, etc. Therefore, a considerable attention was given to propaganda, and the use of religious feelings of the population seemed to be very promising. It was the ministry and its Reich Commissars with their great independence shown since the end of 1941 who defined to a great extent the practical church policy of German bodies in Ukraine, Byelorussia and the Baltic states.

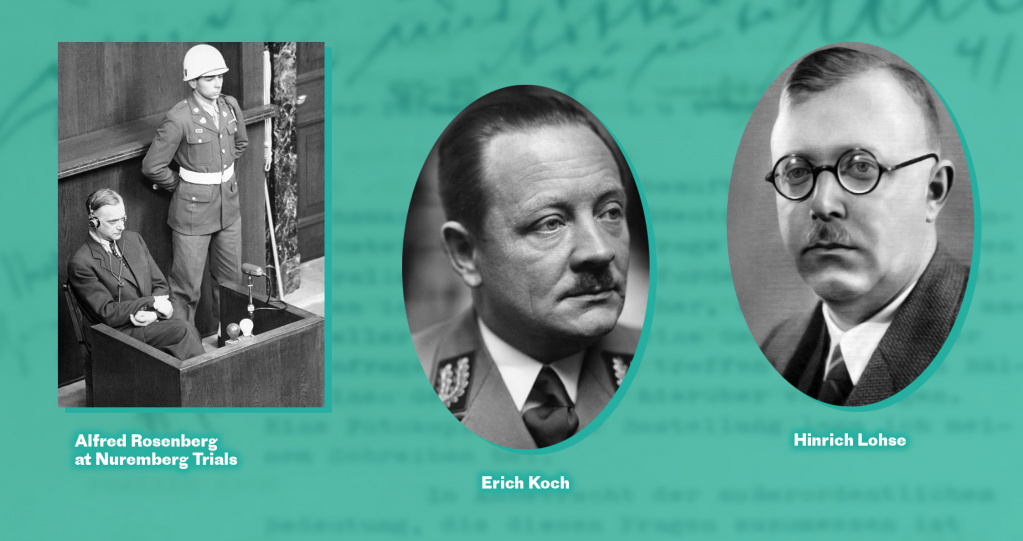

In his evidence given on October 16, 1946, during the Nuremberg Trials, A. Rosenberg stated: ‘After the German troops enters Eastern territories, the army, at its own initiative, granted freedom of worship services; and when I was made Minister of the Eastern Regions, I legally sanctioned this practice by issuing a special decree on ‘Freedom of the Church’ in the end of December 1941’. This decree was really drafted by Rosenberg but because of the opposition of influential opponents, first of all Borman and personally Hitler, it was never published. The development of a fundamental law on religious freedom in the occupied Eastern territories and negotiations about it continued for 7 months, since October to the beginning of May, and ultimately the last 18th draft was categorically rejected by Hitler. It has happened to be in the form of independent decrees of Reich commissars as an abridged version of explanatory instructions for the never adopted law.

The peak of the negotiations fell on summer 1942. By that time the religious upsurge necessitated taking up the church issue in Russia especially seriously. It should be noted that Hitler himself tackled religious problems in real earnest and believed them to be ones of the most important in the task of ‘governing the conquered nations’. On April 11, 1942, he set forth for his circle his vision of religious policy: forced fragmentation of the churches, coercive change of the nature of the population’s faith in occupied regions, prohibition of ‘building unified Churches for any sizeable Russian territories’.

Implementing Rosenberg’s instructions, head of the Reich Commissariat Ukraine (RCU) A. Koch on June 1 and Reich Commissar H. Lohse on June 19 issued identical decrees putting all the religious organizations under the permanent control of the German administration. Any mention of freedom of faith or church activity were altogether absent while priority was given to a procedure for registering associations of the faithful and permitting them to engage in carrying out purely religious tasks.

Thus, by the summer of 1942 the guiding line of the German church policy in the East had been finally worked out, based at that on the opinion of the Party Chancellery and Hitler’s personal instructions. All those who disagreed with their approach had to concede. From this point on this line was not changed in substance, though the Reich Ministry of the occupied Eastern territories and the Wehrmacht command periodically tried to mitigate it somehow.

To prevent a rebirth of the powerful and unified Russian Church, the Nazi, already since the autumn of 1941, gave their support to some Orthodox hierarchs in Ukraine, the Baltic States and Byelorussia who opposed the Moscow Patriarchate and declared their intention to form autocephalous church organizations. Admittedly, the Reich commissars did not share, to varying degrees though, this guideline of the ministry. H. Lohse was tolerant to the well-organized Russian Church and her missionary work in North-West Russia, but he forbade any ecclesio-administrative unification of the Exarchate of the Baltic States with Byelorussia where he, by all means without any success though, promoted the development of church separatism.

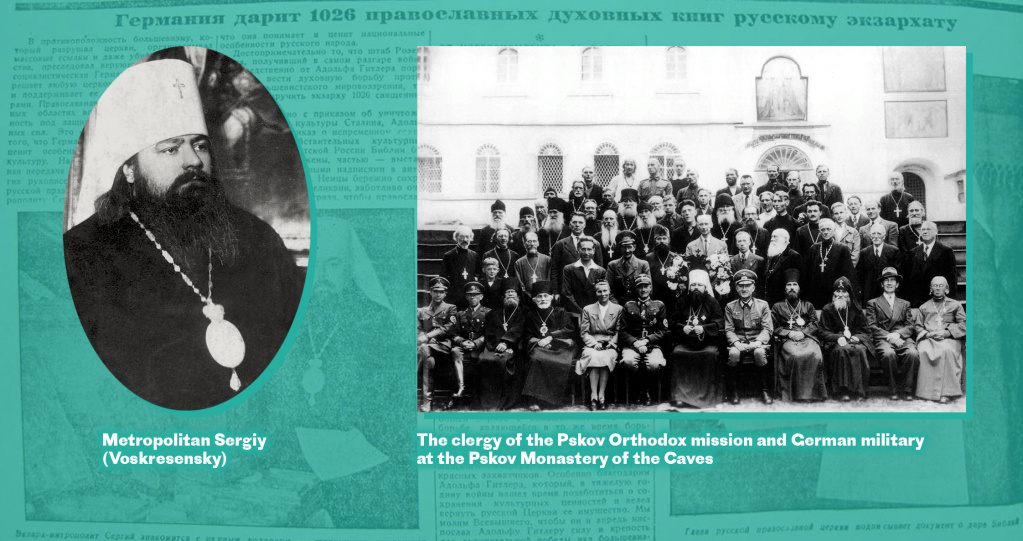

Almost all the Russian regions occupied by German troops were located in the forefront and were governed by the military administration, which in many cases of practical activities mitigated its Nazi guiding line towards the Russian Church. Especially favourable in contrast to other regions was the situation in North-West Russia where the Pskov Orthodox Ecclesiastical Mission worked with success. The head of the Moscow Patriarchate’s Exarchate of Baltic States, Metropolitan Sergiy (Voskresensky) managed already in mid-August 1941 to obtain the military command’s permission to establish the Mission and, up to his assassination (in April 1944), he gave considerable attention to the Mission’s work. The religious rebirth in various regions in Russia went off very actively and was closely connected with the growth of national self-awareness.

Some changes in the Nazi church policy took place in the end of 1943-1944. Wishing to oppose the Soviet propaganda, the RSHA, with the consent of the Party Chancellery, initiated a series of conferences, thus noticeably stirring church life. Initially, they sanctioned a conference to be held from October 8 to 13, 1943, in Vienna, by hierarchs of the Russian Church Abroad despite their very suspicious and hostile attitude to it since 1941. And later, in March-April 1944, a whole series of such conferences took place, two in Warsaw for bishops of the autocephalous and autonomous Ukrainian Churches, in Minsk for hierarchs of the Byelorussian Church and in Riga for the clergy of the Moscow Patriarchate’s Exarchate of the Baltic States.

At the same time, the Reich Ministry of the occupied Eastern territories returned to their old idea of support for national Churches and, in the first place, the creation of a unified Ukrainian Church with holding in future a National Ukrainian Local Council and even with electing the Patriarch, in which connection two suitable candidatures had already been selected. By May 1944, the hierarch of both the autocephalous and the autonomous Ukrainian Churches had already evacuated to Warsaw. In general, in 1944 the Nazi developed an activity in their church policy astonishing to be pursued in the end of the war.

In the beginning of 1945, the last months of the war, the Reich Ministry for the occupied Eastern territories was little engaged in church affairs. Thus, on January 29, Borman wrote to propaganda minister Goebbels that no point of view should be voiced either on radio or in the press concerning the election of a new Patriarch of Moscow (Alexis I). They tried to hush the election simply because they had no arguments for a counter propaganda.

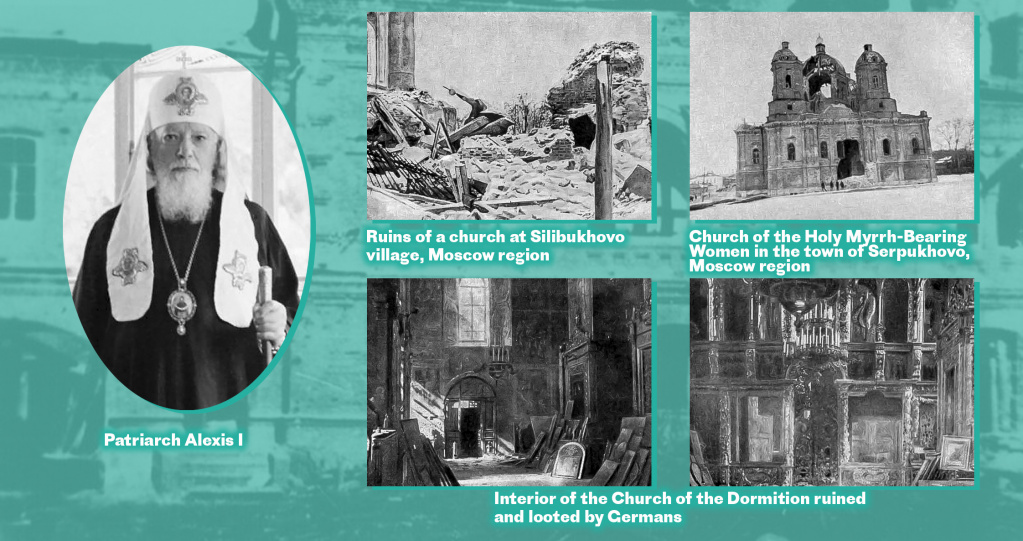

The Nazi actions before their retreat from the occupied regions consisted in the mass burning and looming churches up to the taking down bells, deporting and killing the clergy who spoke of the Nazi’s animosity towards Orthodoxy. In the Leningrad region alone the Nazi destroyed 44 churches, about 50 in the Moscow regions, etc. According to a report of the Extraordinary Commission for identification and investigation of the German invaders’ evil deeds, in total they destroyed and damaged 1670 Orthodox Churches, 69 chapels and 1127 facilities of other religions.

The rapid development of church life in the occupied territory of the USSR began spontaneously and at once acquired mass character. The Nazi policy boiled down to the fragmentation of the Church, using it for assistance to the German administration and liquidation of Orthodoxy after the end of the war. The urge toward ‘atomization’ and liquidation of religious life was manifested in support for the hierarchs who opposed the Moscow Patriarchate. However, the Russian Orthodox Church, though divided to a certain extent into three parts, was actually restored throughout the occupied territory. The attempt to create separatist national Churches failed everywhere except in Ukraine and even there it was followed by a minority of the clergy and faithful. It was not only the religiosity of Russians but also the Russian Church as an organization that proved to be much more powerful and tenacious than the Nazi authorities believed.

Opened churches turned into centres of Russian national self-consciousness and a manifestation of patriotic feelings. A considerable part of the population rallied around them. For only three years of occupation in a situation of starvation, devastation, absence of material opportunities, over 40% of the pre-revolution number of churches were restored. Their total number was minimum 9400. In addition, about 60 monasteries were restored, with 45 in Ukraine, 6 in Byelorussia and 8 or 9 in the RSFSR.

The consequences of the rebirth in the occupied territory of the USSR were great. Undoubtedly, it made a noticeable impact on the change made by the religious policy of the Soviet leadership in the war years. The religious upsurge showed that the 1920-1930 persecutions could not abolish people’s faith and foundations of parish life.

The religious life in the occupied territory of the USSR immediately became a sphere of acute ideological and propagandistic struggle between Nazi Germany and the Soviet State, on one hand, and the Moscow Patriarchate on the other. At the first stage of this struggle, the odds were in Germany’s favour but then it began losing it. The church work under the occupation was increasingly controlled from Moscow and Ulyanovsk (the residence of the head of the Russian Orthodox Church, Metropolitan Sergiy (Stragorodsky) from October 1941 to August 1943.

Since 1943, the Soviet command and the Patriarchate moved in coordination to offensive actions. There were increased attempts to broaden the influence on religious life in the occupied territory. And they were partly a success as relations were established with Metropolitan Alexander (Inozemtsev), Sergiy (Voskresensky) and several other hierarchs. Propaganda actions considerably increased. As a result, in the period from 1943 to 1944 the portion of supporters of the Moscow Patriarchate among the clergy in the occupied regions kept growing. And after the Nazi troops were driven away, an overwhelming part of Ukrainian, Byelorussian and Baltic Orthodox parishes relatively painlessly joined it. It was even easier to deal with monasteries. In the occupation period almost all of them claimed to belong canonically to the Moscow Patriarchate. Thus, by the end of the war Nazi Germany suffered defeat not only in the military and economic areas but also in the sphere of religious policy.