From Pentarchy To Diptychs

How the ‘order of honour’ is determined in the Orthodox Churches

By Pavel Kuzenkov, Candidate of Historical Sciences, Associate Professor

In the Orthodox Church it is the Lord Jesus Christ who is venerated as the one true Head to whom was “given all authority in heaven and on earth” (Mt 28.18). If in the Catholic Church the Pope enjoys “full, supreme and universal authority over the whole Church” (The Catechism of the Catholic Church), then in the Orthodox tradition the primates of the autocephalous Orthodox Churches are considered equal in their episcopal dignity. At the same time, there exists between them an established order of honour according to which they are commemorated in the liturgical diptychs. How was this centuries-old tradition formed?

Christ and the apostles on primacy in the Church

The gospels show that the Lord did not choose any of the apostles as a “leader” who would enjoy special rights over the others. Moreover, Jesus Christ cut short all attempts by his disciples to determine which of them enjoyed any advantage (Lk 22.24-30; Mt 18.1-2) and said to them: “The greatest among you must become like the youngest, and the leader like one who serves” (Lk 22.24-26; cf. Mt 23.11-12). Upon this he gave them an example of this unusual understanding of authority by washing the feet of the apostles at the Last Supper.

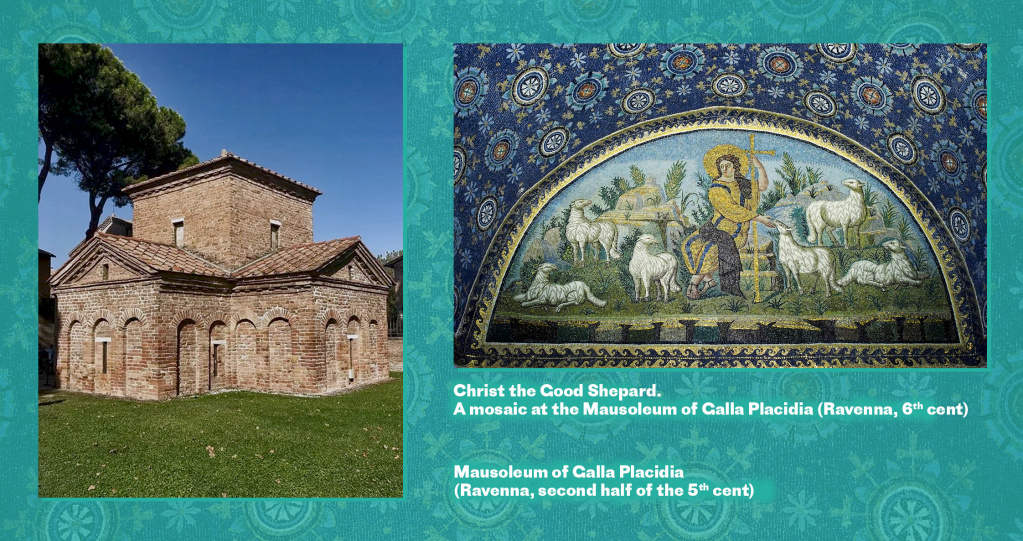

A system whereby the higher one is in authority then the greater the number of subordinates oneserves was incomprehensible to the pagans. And indeed, in the context of “this world” it is unthinkable. But in Christ’s Church for two millennia this principle of love has reigned supreme, a principle opposed to that based on the force and pride of the provisions of worldly power. The ideal of ecclesiastical leadership is the biblical Good Shepherd who lays down his life for those who have been entrusted to his care (Jn 10.11-16; cf. Is. 40.11 et al.).

The Birth of the Hierarchy

The apostle Paul early on mentions the ecclesiastical ministry of a bishop (literally, ‘supervisor’, ‘overseer’) and a deacon (literally, ‘servant’) (1 Tm 3). At first the bishop was barely distinguishable fr om the presbyters (‘elders’) who administered communities in the apostolic period (Acts 15.23, 16.4 et al.). Fr om the second century onwards, bishops received the exclusive power to “bind and loose”, headed the eucharistic assemblies and led the worship of the faithful as the successors to the apostles.

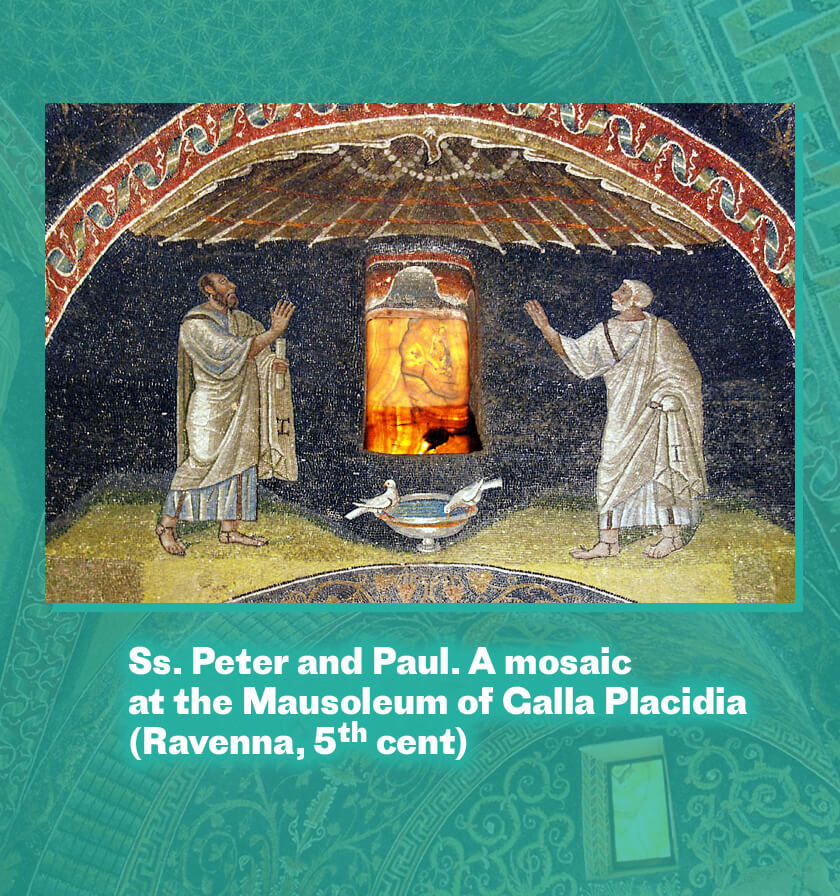

The bishop of Rome – the imperial capital and burial site of the most authoritative apostles Peter and Paul – enjoyed special prerogatives. By the second century he was already considered to be the most influential bishop not only within the Roman empire but also beyond its confines.

Councils and Conciliarity

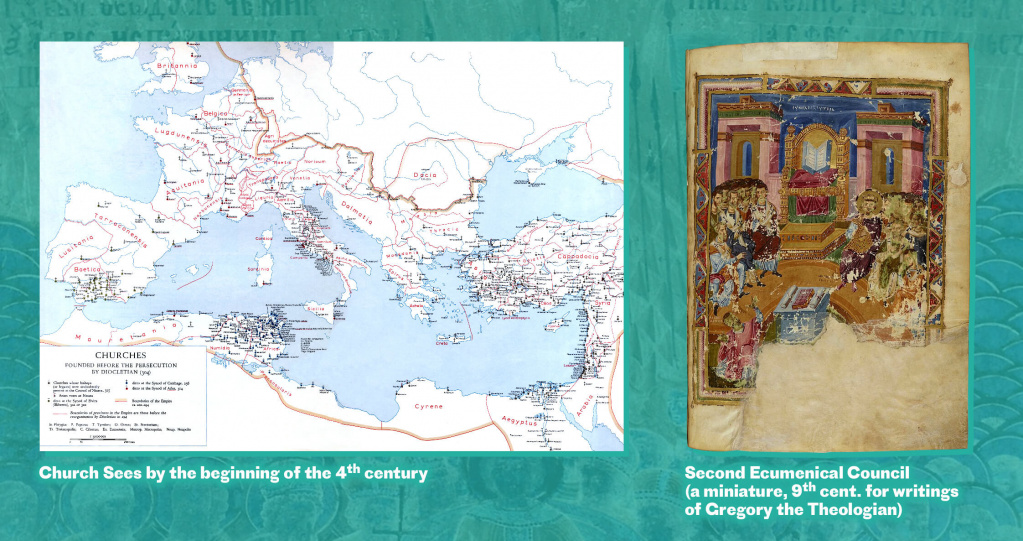

By the third century there appeared assemblies (councils) of bishops in cities of a particular Roman province (in Greek, eparchia) under the presidency of the bishop of the main city, the metropolis. The senior bishop (metropolitan) was obliged to take counsel from the bishops within his province and they in turn would respect him as their head. At the same time, within their own districts the bishops remained masters with full powers (34th Apostolic canon; 9th canon of the Council of Antioch).

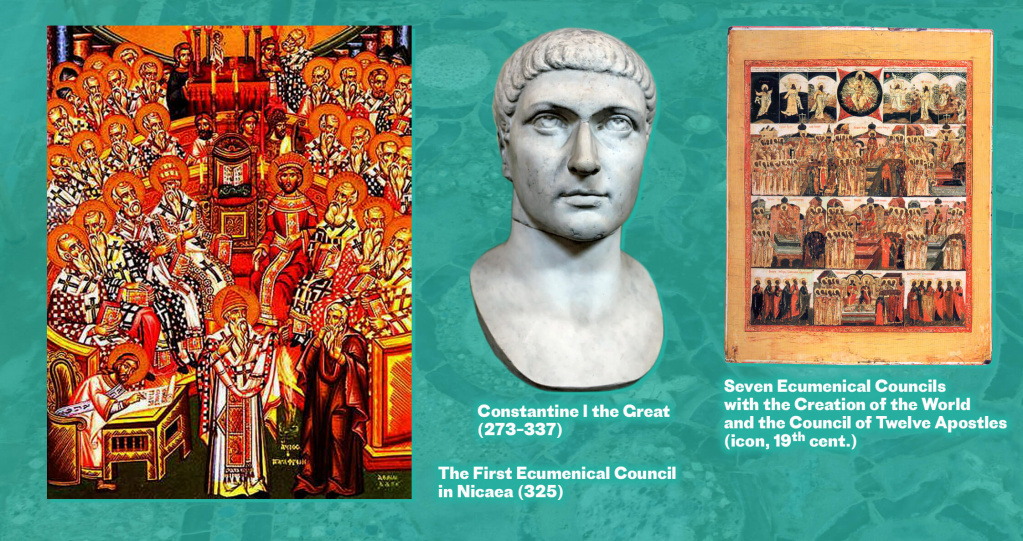

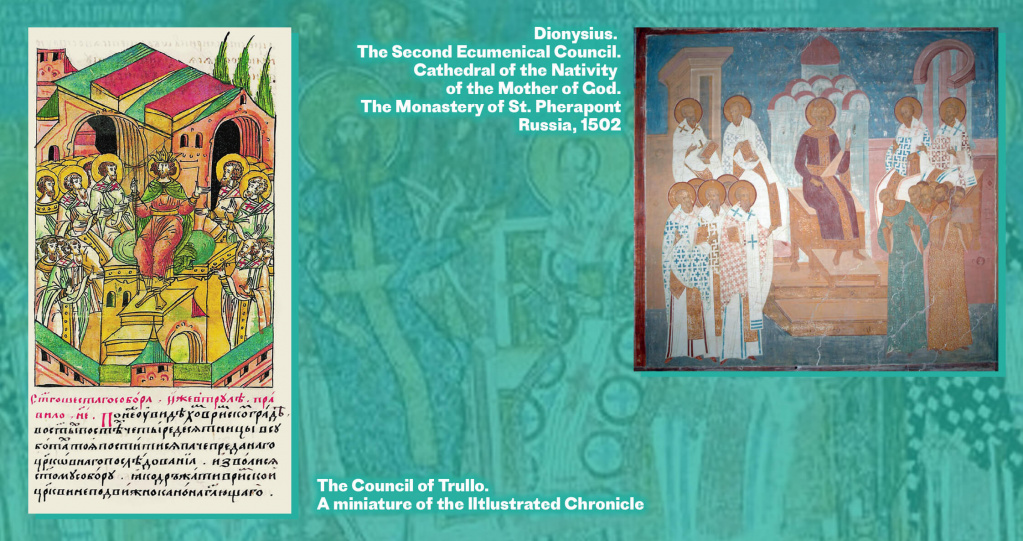

In 325 AD the first Christian emperor Constantine the Great invited bishops to Nicaea to celebrate the jubilee of his reign. The gathering was the first of a number of assemblies of bishops convoked by the state to regulate disagreements within the Church. The seven Ecumenical Councils from the fourth to the seventh centuries formulated the dogmatic and doctrinal foundations of Orthodoxy and catholicity.

Since the episcopate at the Ecumenical Councils had gathered from all over the empire, there arose a need for a ceremonial hierarchy for the higher clergy. Originally the status of the bishops depended upon their personal authority. But by the Council of Nicaea in 325 the 6th canon of the First Ecumenical Council laid down that

“The ancient customs be maintained in Egypt, in Libya, and in the Pentapolis so that the bishop of Alexandria has authority over all these territories, since for the bishop of Rome there is a similar practice and the same thing concerning Antioch; and in other provinces, let the prerogatives of the churches (of the capitals) be safeguarded.”

It was precisely this canon that would later be used by the popes as the basis for their claims to so-called primacy. It is a curious fact that in the ancient Latin versions this canon begins with words that are absent in the Greek original: “The see of Rome has always enjoyed primacy.” But in reality, the canon speaks only of the recognition of the rights of the bishops of the largest cities in relation to the bishops of the surrounding provinces.

The Two Romes

The founding in 330 AD of the city of Constantinople threw down a challenge to the former political and ecclesiastical tradition in which Rome did not have nor could have any competition. The ‘eternal city’ was viewed not only as a symbol of the might of the Roman ‘super state’, but also as the sacred guarantee of the existence of the world itself. Christian writers, too, believed that Rome’s waning would lead to a universal catastrophe. There then appeared in the east a New Rome to which the emperor moved. The emergence of a new capital demanded a re-examination of the system fixed at Nicaea of the ‘prerogatives’ of the ecclesiastical sees. The bishop of the small city of Byzantium, upon which Constantine the Great built the New Rome, was an ordinary bishop of the province of Thrace which was subject to the metropolitan of its capital Heracleia. But this status could not correspond to that of an imperial capital which had rapidly developed into a megapolis. And so, at the Second Ecumenical Council in Constantinople (381 AD) the following 3rd canon was adopted:

“As for the bishop of Constantinople, let him have the prerogatives of honour after the bishop of Rome, seeing that this city is the new Rome.”

The New Rome was equal to the Elder Rome not only according to political but also to ecclesiastical status. However, the nature of the “prerogatives of honour” of those subject to her were not set out, which sparked a series of conflicts. The bishops of Constantinople, who had no province of their own, started to extend their authority as far as circumstances would allow, which evoked protests from the neighbouring metropolitans. Particular acute was the reaction of Ephesus, a megapolis in Asian Minor, proud of its status as the see of St. John the Theologian.

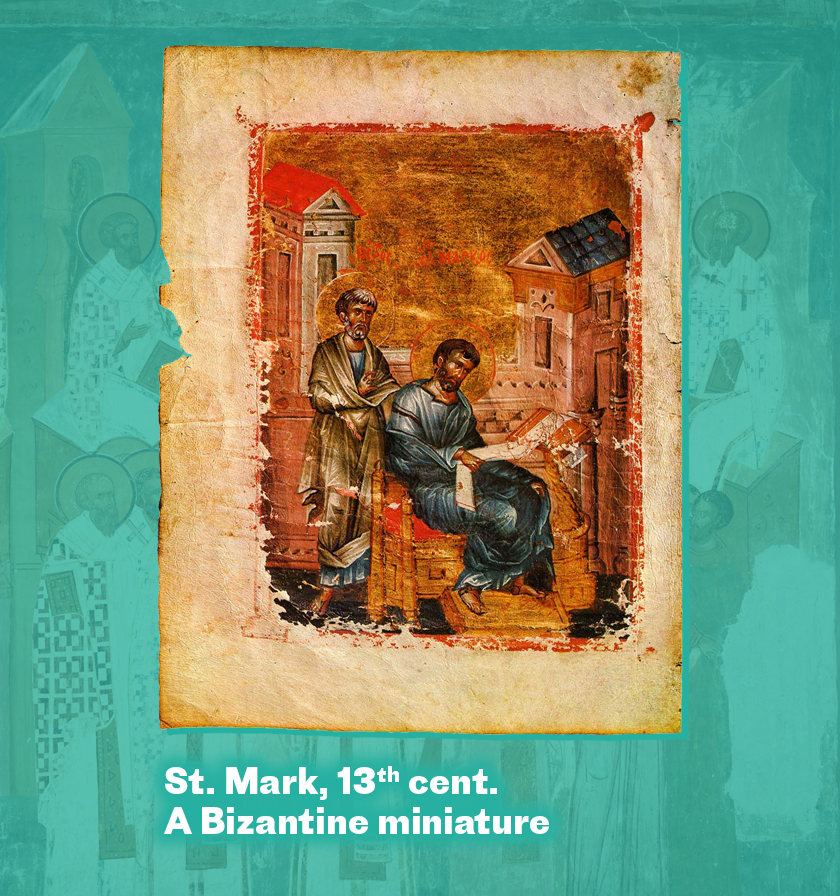

In the west the Second Council was not immediately recognized as an ecumenical council, and the aforementioned canonwas ignored by the popes who continued to regard the three sees listed in the canon of Nicaea – Rome, Alexandria and Antioch – as the most important ones. The leaning on ancient tradition, which was customary for Rome, and a tendency to elevate the authority of a particular see to apostolic times played a role in this. The Church of Rome was traced back to Ss. Peter and Paul; the two main apostles were also active in Antioch, while the see of Alexandria was founded by Peter’s disciple the evangelist Mark. But what could Byzantium boast of, which prior to this had been an insignificant small city? It was only many centuries later that there appeared the tradition that St. Andrew had once been here, which would transform Constantinople into an apostolic see, one founded by the first-called apostle, the older brother of St. Peter.

The 28th Canon of Chalcedon and the Jurisdiction of Constantinople

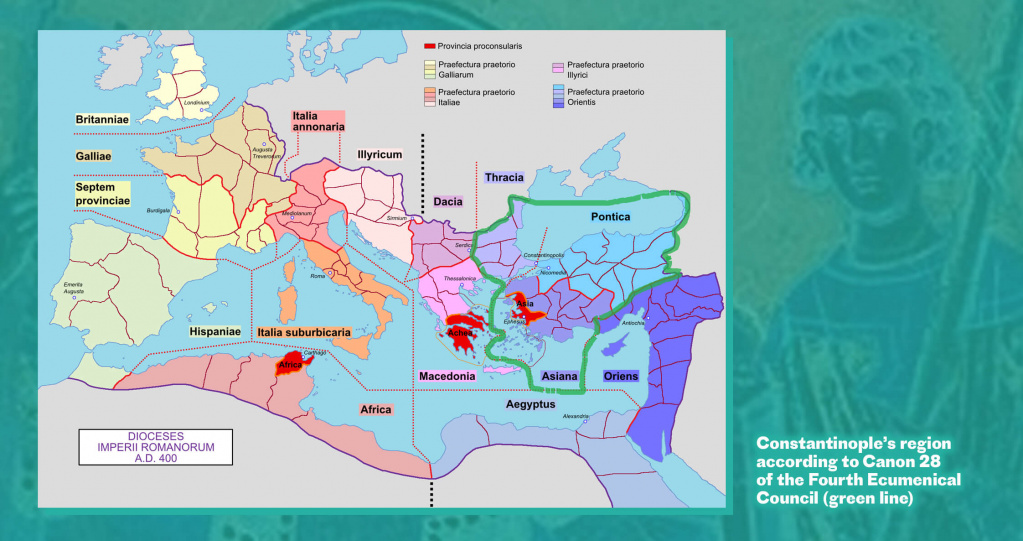

It was impossible to deny Constantinople’s ecclesiastical gravitas, especially after the division of the Roman empire into two halves in 395 AD and when its western half fell into further decline. Moreover, there was a requirement to define formally the confines of the jurisdiction of the New Rome so that its patriarch (this was how the main bishops were styled from the fifth century onwards) would not intervene in other provinces. So, in 451 AD the Fourth Ecumenical Council of Chalcedon adopted a number of important canons, among which special significance was attached to the 28th canon:

“Following in every detail the decrees of the holy fathers, and taking cognizance of the canon just read of the 150 bishops dearly beloved of God who gathered under Theodosius the Great, emperor of pious memory, in the imperial city of Constantinople, New Rome, we ourselves have also decreed and voted the same things concerning the prerogatives of the most holy Church of the same Constantinople, New Rome. For the fathers rightly acknowledged the prerogatives of the throne of the Elder Rome because it was the Imperial City, and moved by the same consideration the 150 bishops beloved of God awarded the same prerogatives to the most holy throne of the New Rome, rightly judging that the city which is honoured by the imperial authority and the senate and enjoys the same [civil] prerogatives as the imperial city of the Elder Rome, should also be magnified in ecclesiastical matters as she is, being second after her. Consequently, the metropolitans – and they alone - of the dioceses of Pontus, Asia and Thrace, as well as the bishops of the aforementioned dioceses who are among the barbarians, shall be ordained by the aforementioned most holy throne of the most holy Church of Constantinople. Each metropolitan of the aforementioned dioceses, along with his fellow-bishops of the province, ordains the bishops of the province, as has been provided for in the canons; but the metropolitans of the aforementioned dioceses, as has been stated, shall be ordained by the archbishop of Constantinople, after proper elections have been made according to custom and have been reported to him.”

These canons are extremely important as it is upon them in the twentieth century some theologians will attempt to construct a theory of the ‘universal’ ecclesiastical jurisdiction of Constantinople (Istanbul). But it is enough to read these texts attentively to realize that they do not speak of ‘universal jurisdiction’. On the contrary, the fathers of the council lim it the powers of the archbishop of Constantinople in according him the right to ordain metropolitans of three dioceses as well as bishops for the barbarian peoples of these particular dioceses. Within the Roman empire of this time there were many Germanic and other tribes who had settled within the empire as allies (foederati); they were not part of the imperial administrative structure and their ecclesiastical structures were headed by special bishops who were in direct submission to the patriarch.

Thus, the 28th canon of Chalcedon made Elder Rome and New Rome equal in their privileges and determined for Constantinople’s ecclesiastical sphere the three dioceses of Asia, Pontus and Thrace.

The Five ‘Patriarchates of the Ecumene’

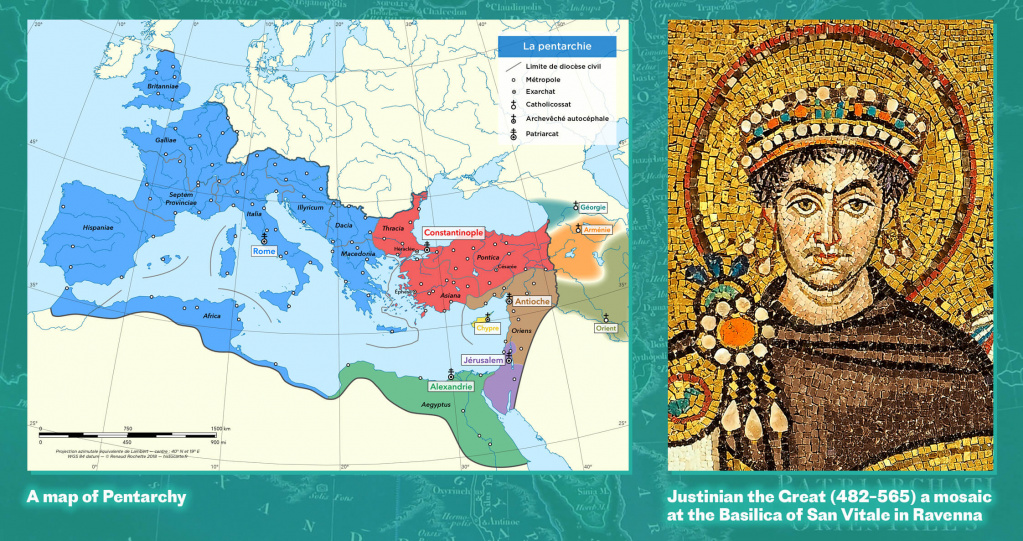

The same Council of Chalcedon took yet one more important decision. The holy city of Jerusalem was finally transformed into a special church district. Thus, there emerged the five main sees of the Roman empire whose primates were accorded the title of patriarch: Rome, Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch and Jerusalem. Their areas of jurisdiction were extremely varied in their administrative divisions: from the entire western empire with the adjoining prefecture of Illyricum near Rome to a number of small provinces under Jerusalem. And yet, the ‘western patriarchate’ was a conditional fiction: in the fifth century the western Roman empire had ceased to exist and Rome’s control over her ecclesiastical structures which had arisen upon the ruins of the barbarian kingdoms was tenuous. Moreover, the Church in Latin Africa forbad appeals ‘beyond the sea’, that is, to Rome (the 32nd, 37th 118th and 139th canons of Carthage), while the archbishop ofAquileia (Grado, Venice) also laid claim to the title of patriarch.

The emperor Justinian the Great appealed to Rome and Constantinople as the main sees of the empire (edict of 533; 131st novella of 545), while the fullness of the Catholic and Apostolic Church was reduced by agreement to the five ‘most holy patriarchs of the Ecumene’ and the bishops subject to them (109th novella of 541). At this added to the titles of the archbishop of Constantinople was the honorary name of ‘Ecumenical Patriarch’ which underscored the status of New Rome as one of the patriarchates of the Ecumene (as the Roman empire grandly called itself).

The Pentarchy in Byzantium in the Middle Ages

The final canonical formulation of the system of five patriarchates occurred in 692 at the QuinisextCouncil in Trullo. The 36th canon states:

“Renewing the enactments by the 150 Fathers assembled at the God-protected and imperial city, and those of the 630 who met at Chalcedon; we decree that the see of Constantinople shall have equal privileges with the see of Old Rome, and shall be highly regarded in ecclesiastical matters as that is, and shall be second after it. After Constantinople shall be ranked the see of Alexandria, then that of Antioch, and afterwards the see of Jerusalem.”

A different order of the ‘main sees’ was adopted in the west. In the Donation of Constantine (a well-known eighth-century forgery advocating political authority for the papacy) Rome is viewed as having under her jurisdiction Alexandria, Antioch, Jerusalem and Constantinople. The author of this early medieval forgery brazenly claimed the decree was dated 315 when Constantinople as such did not yet exist – his main concern was to put Constantinople to the back of the queue! The papacy repeatedly emphasized the secondary status of Constantinople as a patriarchate and objected to the title ‘Ecumenical’, which had already been ascribed to the see of Constantinople in the Byzantine era. In the seventh century all the other eastern sees were conquered by the Arabs and Constantinople remained the sole ecumenical patriarchate on the territory of the empire.

However, the other patriarchs, too, continued to regard themselves as the main bishops of the One Catholic Church. The Pentarchy, all though it was viewed by Byzantine writers as an organic ecclesiastical pleroma like the five human senses, was never understood in terms of being a closed multitude. From the tenth to the thirteenth centuries there emerged independent churches (Serbia, Bulgaria) which were not a part of it. It is an interesting fact that Rome’s falling away (from the fullness of the Church) in the eleventh century in no way altered this conception: Theodore Balsamon (twelfth century) and Matthew Blastares (fourteenth century) speak of the division of the Ecumene between five patriarchs “not including the smaller churches”.

Moscow in Place of Rome

The elevation of the metropolitan of Moscow and All Rus to the rank of patriarch by the Patriarch of Constantinople Jeremiah II in 1589, and confirmed by the councils of the Eastern Patriarchs in 1590 and 1993 added a new interpretation to the Pentarchy. St. Job, Patriarch of Moscow and All Rus, offered the following commentary on this:

“Instead of the pope we are to venerate as our holy father the Great Lord Jeremiah, archbishop of Constantinople the New Rome and Ecumenical Patriarch, and then in order the four patriarchs of Alexandria, Antioch, Jerusalem and of the primatial see of Moscow of the realm of Russia.”

The Council of 1590 laid down that henceforth the patriarch of Constantinople is to be the first and the patriarch of Moscow to be the fifth. And at the Council of 1593 it was proclaimed that Moscow is to be a patriarchate out of respect for Russia’s political status: “For God has deemed this country to be a realm.”

Thus, Moscow received the title of patriarchal dignity as the capital of the sole Orthodox kingdom in the world in much the same way as this once happened with Constantinople. It is true that Moscow was elevated to a position equal to Constantinople but was accorded the last – fifth – place in the Pentarchy.

At this time the four eastern patriarchates were located on the territory of the largest state in the Islamic world – the Ottoman empire. At the same time, the patriarch of Constantinople enjoyed the rights of an Orthodox millet which accorded him certain freedoms. However, when the Phanar (the district wh ere the patriarch’s residence is located) tried to undermine the canonical rights of its brothers in Alexandria, Antioch and Jerusalem, it received a firm rebuff.

The Recent Claims of Constantinople and the Position of the Russian Church

In the twentieth century, after the emergence of the Republic of Turkey and the deportation from Asia Minor of the Greek population, the position of Constantinople became complex. And then the ecumenical patriarchs, with the support of the Triple Entente, decided to transform their honorary status to a real status of ‘Patriarch of the Ecumene’. Taking advantage of the grave situation which the Church of Russia found herself in as she endured unprecedented persecution, Constantinople began to unilaterally and uncanonically take under her ‘supreme jurisdiction’ the Local Churches which had emerged in the new nation states of Eastern Europe. By re-interpreting the 28th canon of Chalcedon, the Phanar started to view as ‘Barbarians’ all those peoples who did not have their own ancient Orthodox Churches and extended its authority over them.

Not content with the traditional canonical status of ‘first among equals’, the patriarchs of Constantinople started to lay claim to the position of ‘universal bishop’, the ‘first without equals’, as one of the subscribers to this idea the archbishop of America Elpidophoros (Lambriniadis) said. An important step on this path was the organization and the holding of the ‘Holy and Great Pan-Orthodox Council’ on Crete in 2016 in spite of the objections of a number of Orthodox Churches and which attempted to grant to Constantinople the right to be a ‘coordinator’ between the other Orthodox Churches. We can judge the nature of this ‘coordination’ by the actions of Patriarch Bartholomew with regard to the non-canonical Orthodox Church of Ukraine. These actions, which are a gross violation of the ancient canons, have sown and continue to sow confusion in the One Orthodox Church.

The Russian Orthodox Church adheres strictly to the apostolic principle of conciliarity and recognizes the equality of the canonical rights of the primates of all the fifteen autocephalous Local Churches, among which are the Churches of Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, Jerusalem, Russia, Georgia, Serbia, Romania, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Greece, Albania, Poland, the Czech Lands and Slovakia, and America. All of these sister Churches are equal members of the One Catholic and Apostolic Church of Christ.